In an emotional scene in the popular TV medical drama, “The Pitt,” lead actor Noah Wyle, as Dr. Michael “Robby” Robinavitch, counsels parents distraught about their terminally ill son, Nick.

The scene takes place after the mother and father on the Max show accept that their son is brain dead and honor his wish to donate his organs.

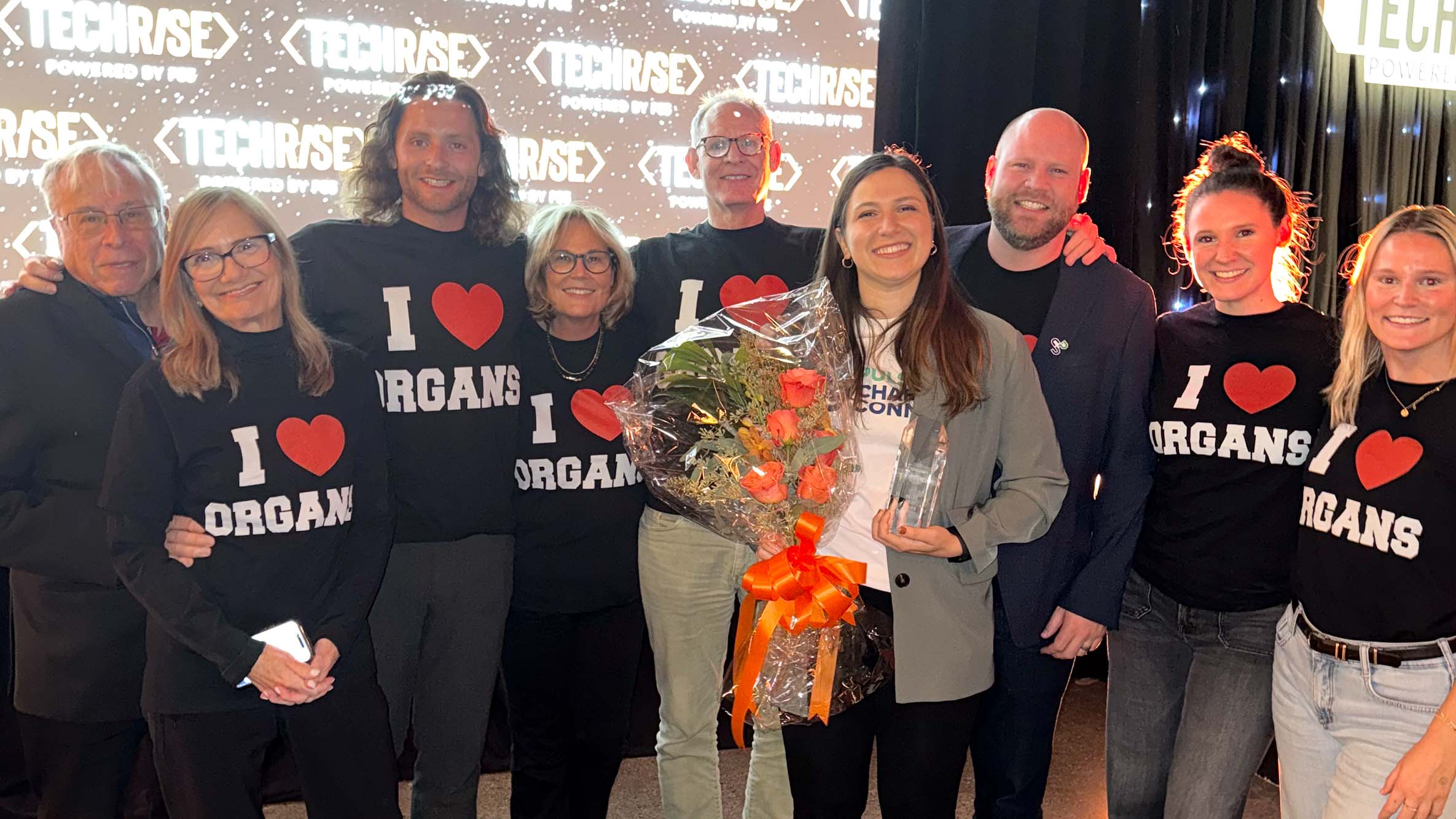

Laura Epstein, holding flowers, is the founder and CEO of Pulse Charter Connect. The 2016 graduate won a $100,000 grant at the 2024 TechRise Chicago Pitch Competition. (Contributed photo)

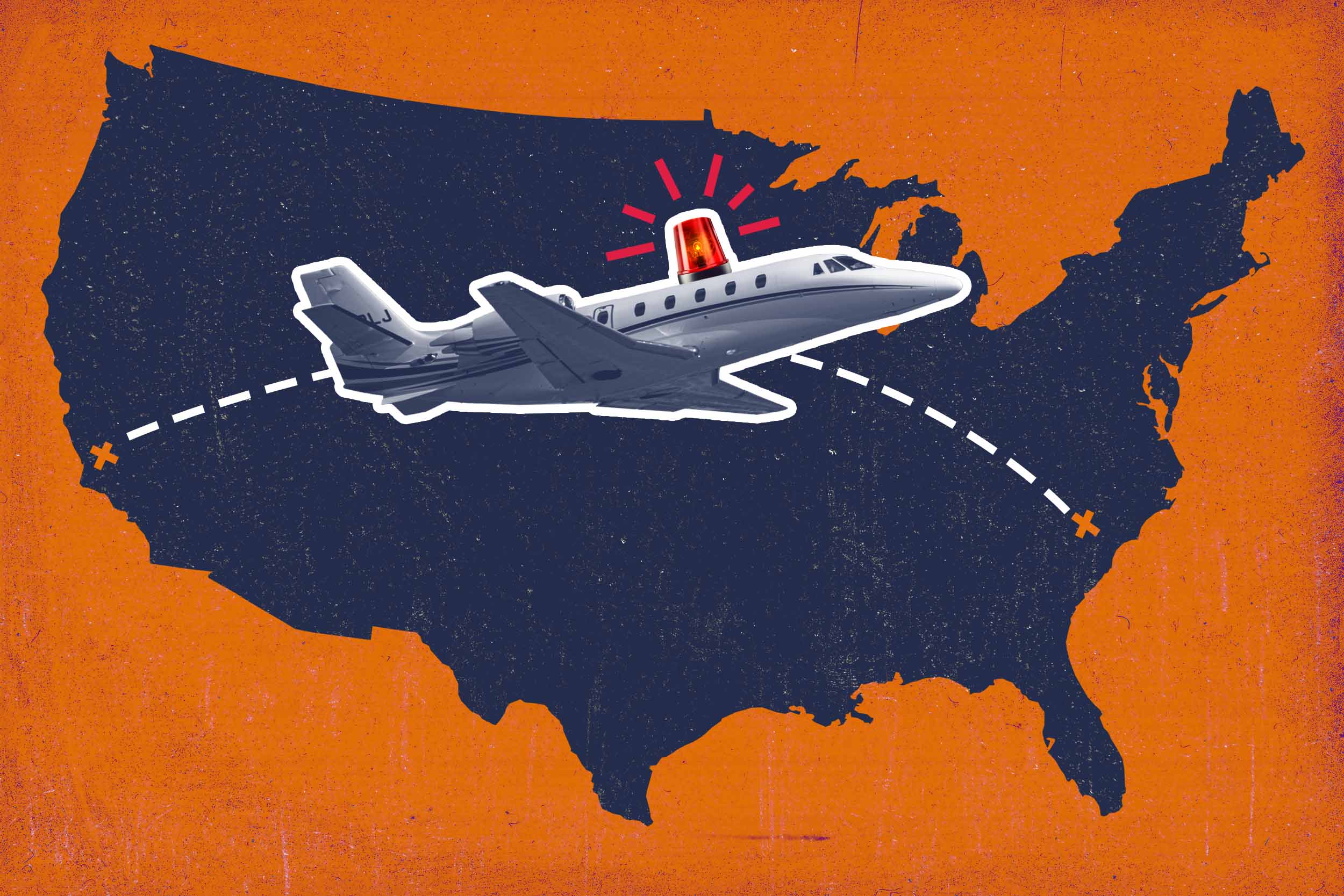

“Surgical teams are flying in from all over the country to meet Nick at the Center for Organ Recovery,” Dr. Robby tells them, assuring them Nick will be in good hands.

It was not so long ago that those flights were not happening with great frequency in the real world. That’s changing in part because of Laura Epstein, a 2016 University of Virginia graduate who earned her aerospace engineering degree in Charlottesville while also collecting her pilot’s license.

Epstein, third from left, has her pilot’s license. She earned it after UVA’s Alumni Association gave her the Women With Wings Award, which supports women in the School of Engineering and Applied Science who to learn to fly airplanes. (Contributed photo)

Viable Organs Go Unused

The organ donation ecosystem is complex and inefficient. More than 100,000 people in America are on the transplant waiting list. Only 45,000 transplants are performed each year. Because of transportation delays, geographic barriers and the challenges of quickly matching donors and recipients, 28,000 viable organs go unused annually.

To help, Epstein launched a business, Pulse Charter Connect, a year ago. It enables hospitals to streamline the donation process, replacing potentially countless phone calls with her new tool.

“We created a digital platform … tailored to the needs of the transplant community,” Epstein said. “So a transplant coordinator would use our platform to request transport and then follow it through alongside doing different communications. So if there’s a delay in the operating room or if they need … anything (additional) from a logistics point of view, we facilitate that on our platform.”

Epstein says she hopes to one day help fly organs where they are needed. “We’re a third-party platform that facilitates (organ delivery),” she said. “(I) would love to one day. (I) haven’t had the time to do it myself.” (Contributed photo)

The company offers a vetted network of ground and air transportation providers. Incorporating airplane transportation was always part of the equation for Epstein because of her love of flying. As an undergraduate, she won the Women With Wings Award, which supports women in the School of Engineering and Applied Science who want to learn to fly airplanes.

How It Works

If a heart becomes available in St. Louis for a matched patient in Chicago, “then it’s up to the Chicago team to actually coordinate the transportation,” Epstein said. “So they will have to get their team out to St. Louis for the designated operating room time at that donor hospital to procure the organ and then travel back with it to transplant it into their recipient.”

Dr. Jeff Campsen, Pulse Charter Connect’s medical adviser, removes a kidney stone ahead of kidney transplant surgery. The surgeon has done “thousands” of transplant surgeries in his 15 years as a doctor. (Contributed photo)

It must happen fast. Healthy hearts and lungs are only viable for up to six hours, livers up to 12 hours and kidneys up to 36 hours.

Since last April, Pulse Charter Connect has helped transport 65 organs across the Midwest and Mid-Atlantic regions and is looking to expand westward.

“Their company is trying to help streamline travel and organ transplantation, which is super important because … 10 years ago, organs were mostly transplanted locally,” transplant surgeon Dr. Jeff Campsen, the company’s medical adviser, said.

That’s because outlets like the Center for Organ Recovery, mentioned by Wyle’s character in “The Pitt,” keep national lists to match donors and recipients. “So it’s not about locality, it’s more about illness. So, an organ that is procured in Utah may be matched to the sickest person in Virginia,” said Campsen, who said he has performed “thousands” of transplants during his 15-year career.

The passion for organ donation runs in the family. Campsen’s father, Paul, a retired lawyer living in Norfolk, anonymously donated one of his kidneys to a recipient at UVA Health in May 2021, “because it’s a good thing,” Paul Campsen said.

.jpg)