The U.S. Food and Drug Administration is reviewing a new Parkinson’s disease drug called tavapadon that could give people with the disease more control over their movements.

If approved, it would be the first major new drug treatment for Parkinson’s in half a century. Richard Mailman, a University of Virginia professor of pharmacology and neuroscience, has spent decades trying to bring this class of drug to patients.

As the FDA deliberates and ahead of a UVA Parkinson's fundraiser, Mailman spoke with UVA Today about tavapadon and how it could change life for people living with Parkinson’s.

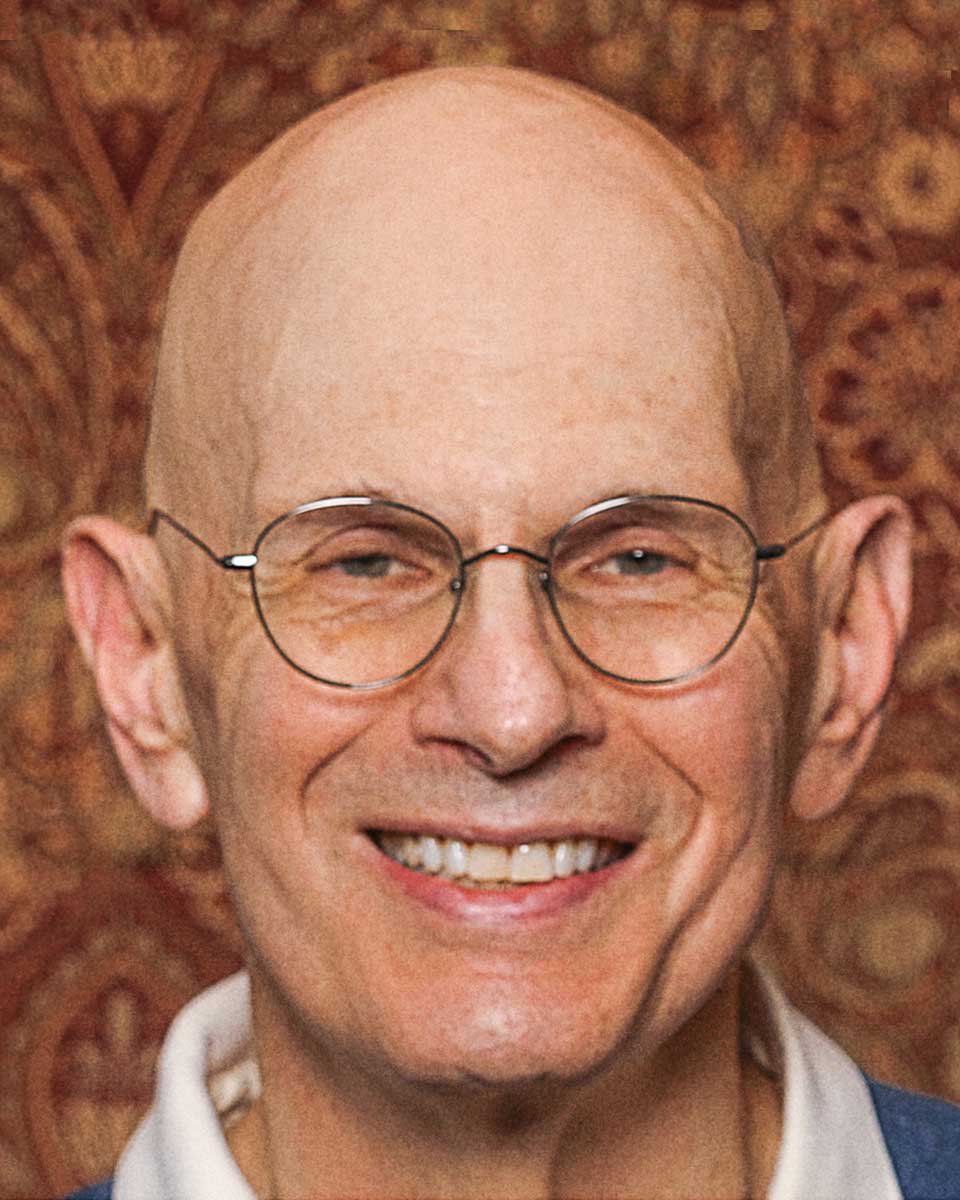

Richard Mailman is a professor of pharmacology and neuroscience. When he set out to develop schizophrenia treatments decades ago, he didn’t imagine he’d stumble onto information that would help with Parkinson’s. (Contributed photo)

Q. How did you come to develop Parkinson’s treatments?

A. I got a doctorate in physiology many years ago and, in the process of doing my thesis work, I became very interested in a class of molecules that I had used as probes to look at functions in the liver. I saw they were candidates to treat central nervous system disorders and started reading about central nervous system disorders, which excited me enough to reorient my career.

A few years later, I ended up as an assistant professor studying the brain. My first idea was to discover new ways to treat schizophrenia, which at that time was treated with a class of drugs that were effective, but had a lot of side effects. By the time I actually got my first NIH grant, I realized all of my early predictions were wrong, and instead I had this new idea of how to treat Parkinson’s disease.

Q. What discoveries helped guide your research toward developing tavapadon?

A. There was a group at Johns Hopkins University that teased apart the neurocircuitry of an area of the brain called the basal ganglia, which is where the D1 dopamine receptor (our drug target) is expressed the most. At the same time, a group at the University of Virginia discovered that the D1 receptor was located in one critical group of cells in the basal ganglia that we thought were important.

Since 1969, the gold standard drug has been levodopa, which makes more dopamine in the brain. The problem was there was no selective drug to activate the D1 receptor. So, we pulled together a team of scientists, and within 10 years we discovered the first drug of this type and tested it in cells, different species of animals, and actually in man. The drug worked but it was only injectable and lasted only for a few hours making it impractical for everyday use.