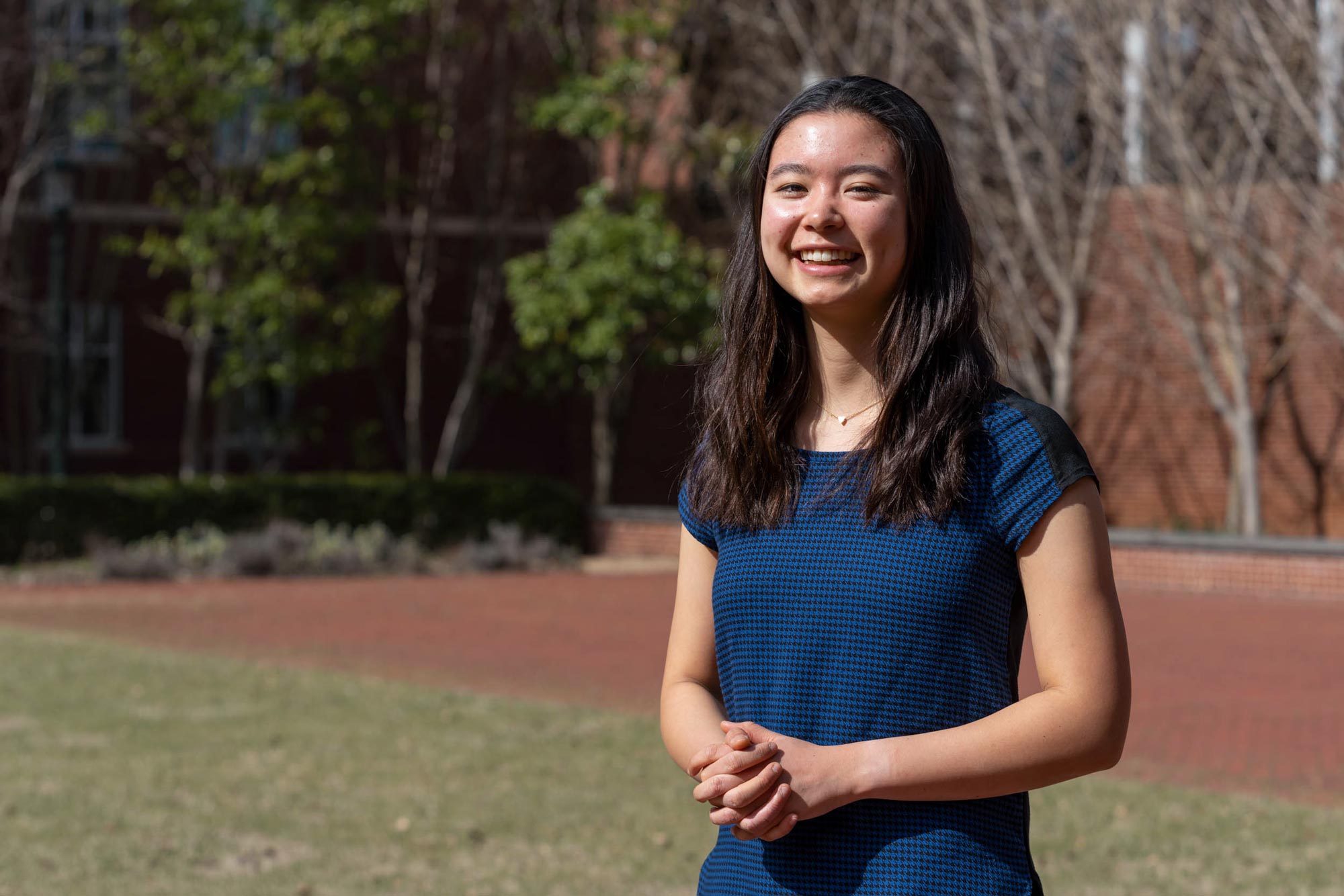

Ailene Edwards is fighting cancer with a bioprinter.

Edwards, a third-year biomedical engineering major at the University of Virginia, is doing this as a Harrison Undergraduate Research Grant recipient. Harrison grants pay up to $4,000 to a student to engage in a research project, with an additional $1,000 for a faculty mentor guiding the research.

“The human body is exceedingly complex and the way cancer cells grow, divide and metastasize is regulated by several factors,” Edwards said. “In traditional 2D cell culture, in which cells are grown on plastic dishes, it is difficult to capture the influence of factors such as other types of cells, the tumor’s proximity to blood vessels and the extracellular matrix.

“Bioprinting offers a way to generate a 3D model of a tumor that is reproducible and better mimics the conditions found in the human body. Our model places cancer cells in a core within a shell of other cell types such as fibroblasts, a type of connective tissue cell, and endothelial, or blood vessel, cells.”

The model can be used as a platform for future cancer research, Edwards said, such as studying how low oxygenation or growth factors influence cancer cell migration within the 3D tumor.

Edwards, of Blacksburg, is currently bioprinting with a human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell line.

“They are called HPAF-II cells and are classified as an immortalized cell line,” she said. “They can be purchased through the American Type Culture Collection. However, in the future and depending on how the model is being used, it would be possible to print with patient-derived cancer cells. For example, if a tumor is biopsied, those cells could be used in the construct. Subsequently, physicians could develop a personalized treatment plan for the patient based on how the cancer cells behaved in the model in response to chemotherapy treatments.”

Bioprinting can give doctors more insight into how the cancer cells are growing and reacting.

“Bioprinting will allow us to create reproducible models of tumors where specific cell types can be positioned relative to one another in ways that mimic real tumors,” said Matthew J. Lazzara, associate professor of chemical engineering, in whose laboratory Edwards is working. “We believe that the architecture of the tumor can influence its progression.”

So how do these biological models work? Using printing nozzles or needles, the cells are extruded in the form of “bio-inks” that are a combination of the cells being utilized and biomaterials such as gelatin and alginate. The gelatin is derived from pigs, while alginate is derived from brown algae, generally biocompatible substances. The models are tiny – about 1 millimeter in radius and less than 1 millimeter in height.