Editor’s note: On Feb. 16, one of the University of Virginia’s rare and valuable copies of the Declaration of Independence, printed in Philadelphia on July 4, 1776, will go on display in the Rotunda from 1-5 p.m. The display is part of UVA250 and VA250, a yearlong celebration of the people, places and events that shaped the nation’s founding 250 years ago, and contributed to the growth of the fledgling democracy.

8 things to know about UVA’s copies of the Declaration of Independence

(Illustration by Tobias Wilbur, University Communications)

Trending

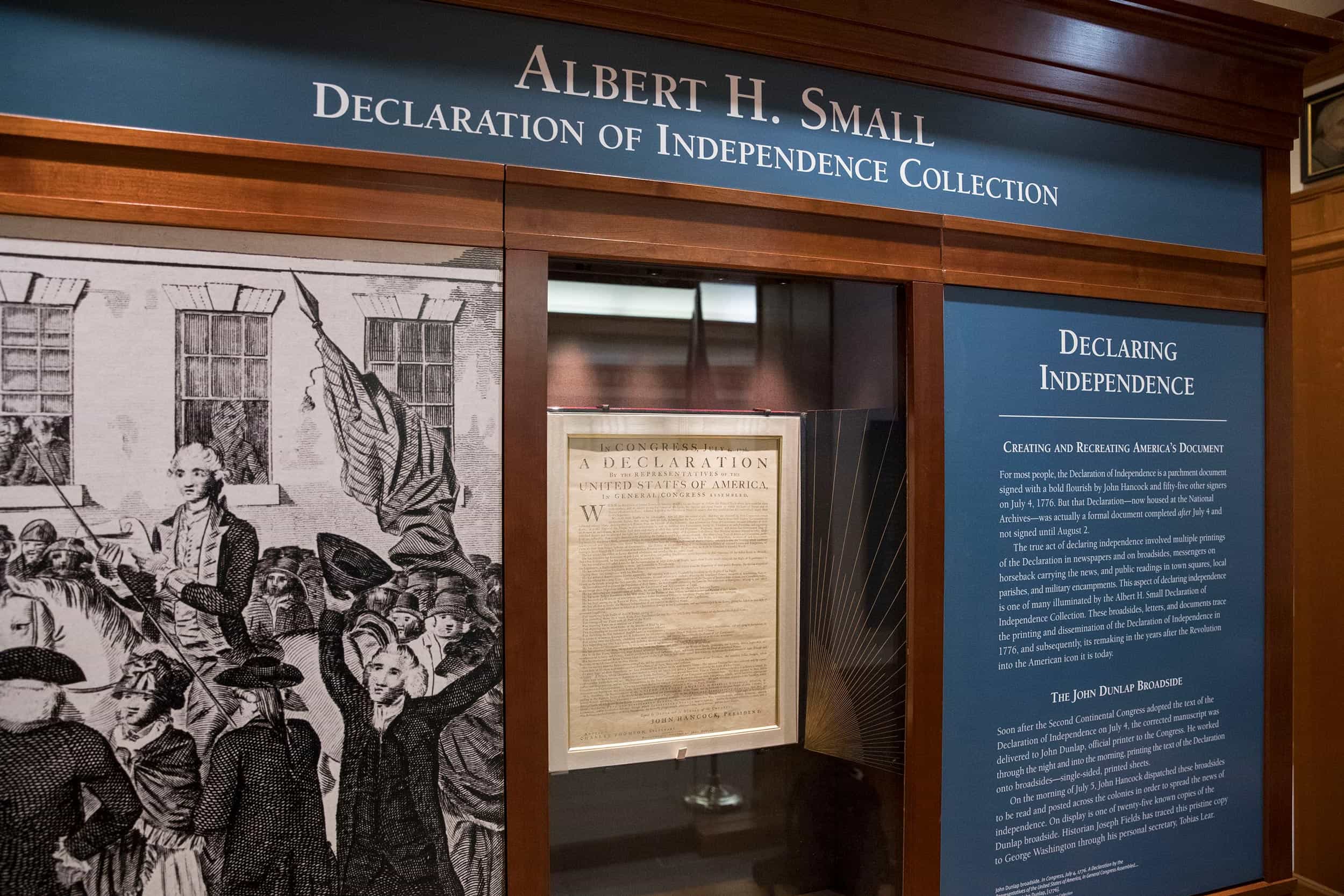

University of Virginia founder Thomas Jefferson, with the help of John Adams and Benjamin Franklin, drafted the Declaration of Independence, and thanks to Albert Small, Mr. Jefferson’s University has an extensive collection of original printings of the document, including two of the first run.

The declaration, approved by the Second Continental Congress, is a seminal document for the nation.

“Eloquently articulating the principles and sentiments that drove patriotic subjects of King George III to resistance and revolution, the declaration has served as a sacred text for subsequent generations of Americans,” wrote Peter Onuf, the emeritus Thomas Jefferson Foundation Professor of History at UVA in the book “Declaring Independence, The Origin and Influence of America’s Founding Document.”

Small, a real estate developer and former member of UVA’s Board of Visitors, started donating his Declaration of Independence collection to the University’s Special Collections Library in 1999.

Here are some things you may not know about the declaration:

There was a printed copy before there was a handwritten, signed copy.

John Dunlap, the official printer of Congress, produced the “broadside,” a large, single-sided sheet, similar to a poster. The only names on that first copy are those of John Hancock, Congress’s president, and Secretary Charles Thomson. The Second Continental Congress adopted it that day, but the 56 representatives did not sign until Aug. 2, nearly a month later.

There was a copy of the Dunlap printing in the Small Collection.

“Albert Small deposited his copy of the Dunlap Broadside in 2003,” said Yuki Hibben, associate librarian and curator of print culture at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. “His copy has a fairly clear provenance. It once belonged to Tobias Lear, executive secretary to George Washington from 1786 to 1799.”

The Dunlap printing in Small’s collection may have belonged to George Washington.

“There is a strong possibility that the Albert Small copy of the Dunlap Broadside, now at UVA, once belonged to George Washington,” David R. Whitesell, former curator of special collections, said in a 2019 interview. “Its provenance can be traced back to the early 19th century, when it was in Tobias Lear’s possession. Lear … is known to have taken several documents, possibly including this broadside, from Washington’s papers shortly after Washington’s death in 1799.”

Special Collections actually has two of the Dunlap printings.

“UVA has two copies of the Dunlap Broadside. The second copy was purchased by the library in the 1950s using endowed funds for the Tracy W. McGregor Library of American History. The McGregor copy bears the watermark of King George III,” Hibben said. “Other copies of the broadside are also known to bear the watermark, with some appearing upside down. Dunlap rushed to print the broadsides for distribution and used whatever paper he had available.”

The gathering of the signers featured in John Trumbull’s 1817 painting does not depict the signing of the document.

“The Dunlap Broadside was printed around July 4, 1776, from Jefferson’s edited copy taken down to John Dunlap,” said George Riser, who is working on a Declaration of Independence exhibit planned for the Small Library in spring 2026, in advance of the 250th anniversary of its adoption. “It was probably cut up in pieces so typesetters could set it very quickly to get it printed that evening. After this document was printed on July 4, some of the delegates left Philadelphia.”

Riser said Timothy Matlack wrote out the engrossed copy of the Declaration of Independence from a printed copy, which became the official parchment copy intended for signing. He was an assistant to Charles Thomson, the secretary of the Second Continental Congress and completed the engrossed version by Aug. 2, 1776, for delegates to sign.

“That’s the document that’s in the National Archives that everybody signed,” Riser said. “The signed document in the National Archives actually comes after this, and some of the delegates had left, so that document was taken up and down the East Coast so that everybody could sign the copy that’s in the National Archives.”

The collection includes Benjamin Owen Tyler’s subscription book for his printing, which contained many historic signatures.

Tyler was a self-taught calligrapher and penmanship teacher who copied and designed the text of the Declaration, making exact copies of the signatures from the signed manuscript, and sold printed copies on subscription.

“He had a subscription book, and he went around to get the most famous signatures first for his subscription book, so then he could use it as a sales document,” Riser said. “There’s Jefferson right off the bat, the first one, and Madison and Adams. So the first three, he had to travel to get their signatures, and then he could use that as a document. This was from 1818.”

The State Department produced an official facsimile of the Declaration of Independence in 1823.

“Engraved by William Stone and printed on parchment, the facsimile was distributed to living signers of the Declaration, high-ranking officials and foreign dignitaries who contributed to the war effort,” Hibben said. “UVA’s copy was presented to Marquis de Lafayette when he visited the United States in 1824.”

Riser said Lafayette kept his copy close, hanging it in his bedroom.

One of the rarest signatures in the Small Collection belongs to Button Gwinnett, the delegate from Georgia.

“You could find a Jefferson signature would be less expensive than a Button Gwinnett, because there are only 51 Button Gwinnett signatures known. I think the last one sold for over $700,000 recently,” Riser said.

The Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library houses two rare first-run printings of the Declaration of Independence. (University Communications photo)

Media Contacts

University News Associate Office of University Communications

mkelly@virginia.edu (434) 924-7291