A literary agent was on the phone with Amy Griffin. She wanted the University of Virginia alumna to pen a volume on women in business.

That made sense. After earning a volleyball scholarship and progressing to team captain, she graduated from Virginia in 1998 and charged into a marketing and investing career. In 2002, she married John Griffin, another successful Wahoo. “I think that’s the only reason he married me, because I went to UVA,” she teased.

Together the power couple funded startups, started a family and supported their alma mater.

But Amy Griffin had a different book idea. She’d written parts of it at 3 a.m. on her bathroom floor, sometimes through tears. It wasn’t about business, but betrayal. Specifically, what a Texas schoolteacher had done to her when Griffin was a young girl.

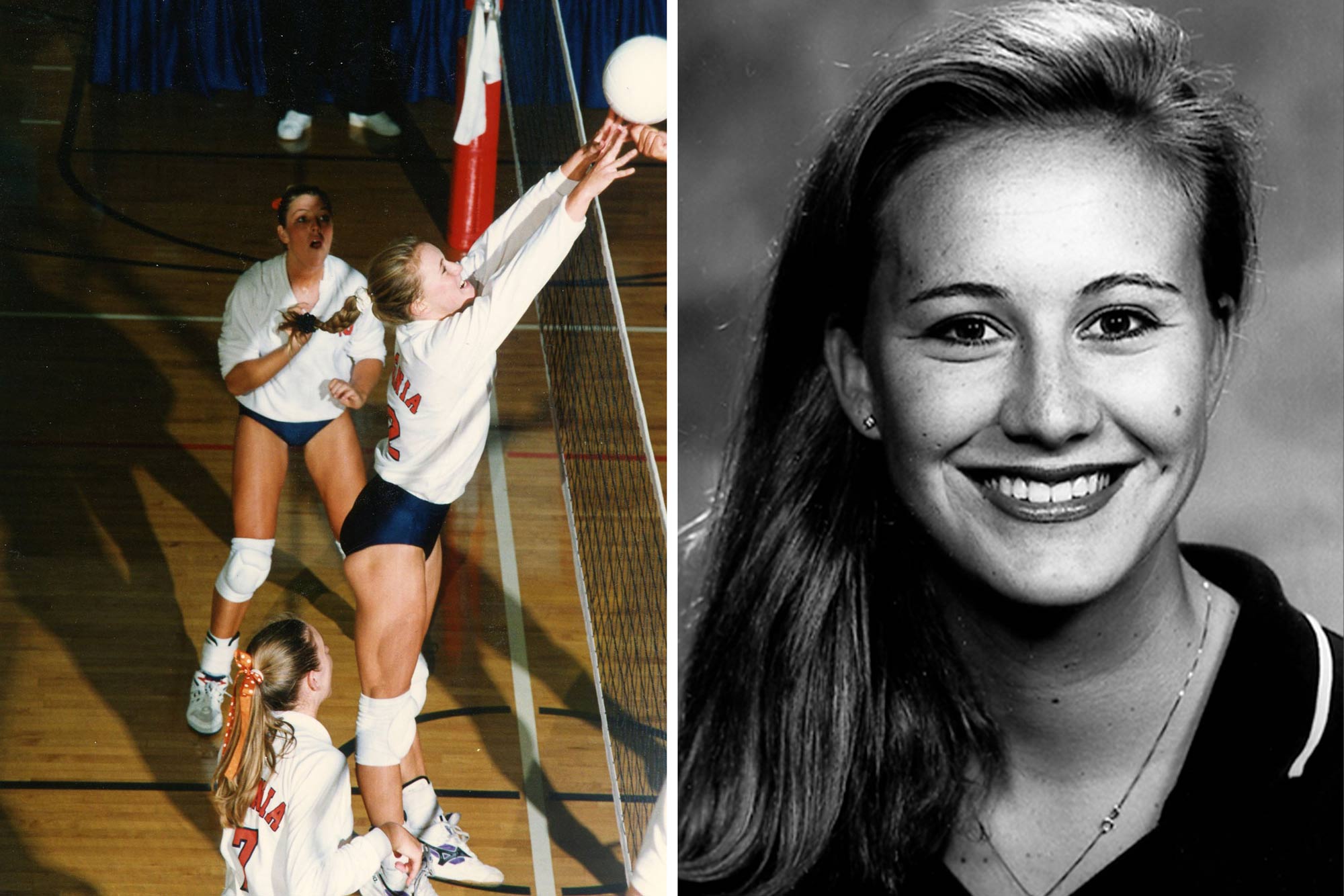

Left, Griffin, twice named the volleyball team’s most valuable player, blocks an attack in the mid-1990s. Right, Griffin smiles for her team portrait. As a Texas high school player, she traveled to Charlottesville to check out the program and immediately committed after seeing Grounds for the first time. (Virginia Athletics photo)

She went to her computer and pressed “send.”

When “The Tell” hit bookstores last month, it caused a stir.

Oprah Winfrey gushed: “I was just floored when I read her story.”

The book landed on the New York Times Bestseller list. Fortune magazine wrote an article. So did Vogue, Elle, People. She was on the “Today” show.

Suddenly, tens of thousands of people were reading how memories Griffin had buried most of her life came pouring out. Her memoir took readers on a journey of how she uncorked the dark secrets of childhood sexual assault, and how the revelation freed her.

‘You’re Not Real’

“I’d built up this wonderful life with all these castle walls that looked perfect,” she told UVA Today. But there was something that kept her from fully connecting with her husband, her kids, herself.

“I had built a life, but I couldn’t participate in it,” she said.

Griffin stands at the base of the steps leading to Memorial Gymnasium, home of UVA volleyball, where Griffin was a team captain. (Photo by Matt Riley, University Communications)

Sensing an emotional barrier, one of her daughters challenged her one night. “She came to me and said, ‘Mom, who are you? You’re nice and you do everything for us, but I really don’t know you,’” Griffin recalled. “‘You’re not real.’”

The jarring conversation launched Griffin on a journey to reconstruct a past she’d closed off. She now sees her move from a small Texas town to Charlottesville to play volleyball as the first step – an escape from something she couldn’t name at the time, though its shadow lingered in her life for decades.

Her husband had been supporting a nonprofit that used psychedelic drugs to help veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder open up about what they had stuffed. After careful consideration, Amy Griffin decided to try that approach.

“I took a pill and within five minutes I said, ‘I’m going to tell you everything that’s going on,’” Griffin said. “And I sat with a therapist and told her for eight hours the abuse that I endured.”

Writing about it became her therapy, Griffin said. Calling upon her UVA English degree, her thoughts flowed into a journal and eventually onto a computer. As painful as it was to dredge up what she’d unconsciously locked away, the experience was cathartic.

“It’s made every relationship better because it’s been more honest and open,” she said. “It’s created this bond, especially with my innermost circle – with my kids and my husband – where there’s just absolutely nothing we can’t talk about.”

‘I’m Not in Control’

With “The Tell” taking off, Griffin had to consider her most personal experiences were now public – shared with work associates, family members and her connections at UVA. But because it was all out there, she had to acknowledge it.

“The only way to show that life isn’t perfect, and to be honest with myself, was to tell that story,” she said. “And to just say, ‘I’m not in control.’”

Some parts of the manuscript were so painful she tried to claw them back. But her literary agent urged her to keep them in, to tell her full story. She agreed.