Best known for his 1871 painting “Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1” – also called “Portrait of the Artist's Mother” – and his well-publicized legal battle with the English art critic John Ruskin, the 19th-century American artist James McNeill Whistler often garners as much attention for his flamboyant personality as for his artistic production.

Yet a look at the artist’s early landscapes and portraits demonstrates a different side: the development of his search for his artistic vision.

The Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia will feature Whistler’s works in two upcoming exhibits: “Becoming the Butterfly: Landscapes of James McNeill Whistler,” which runs from Jan. 25 through April 28, and “Becoming the Butterfly: Portraits of James McNeill Whistler,” from April 30 through Aug. 4.

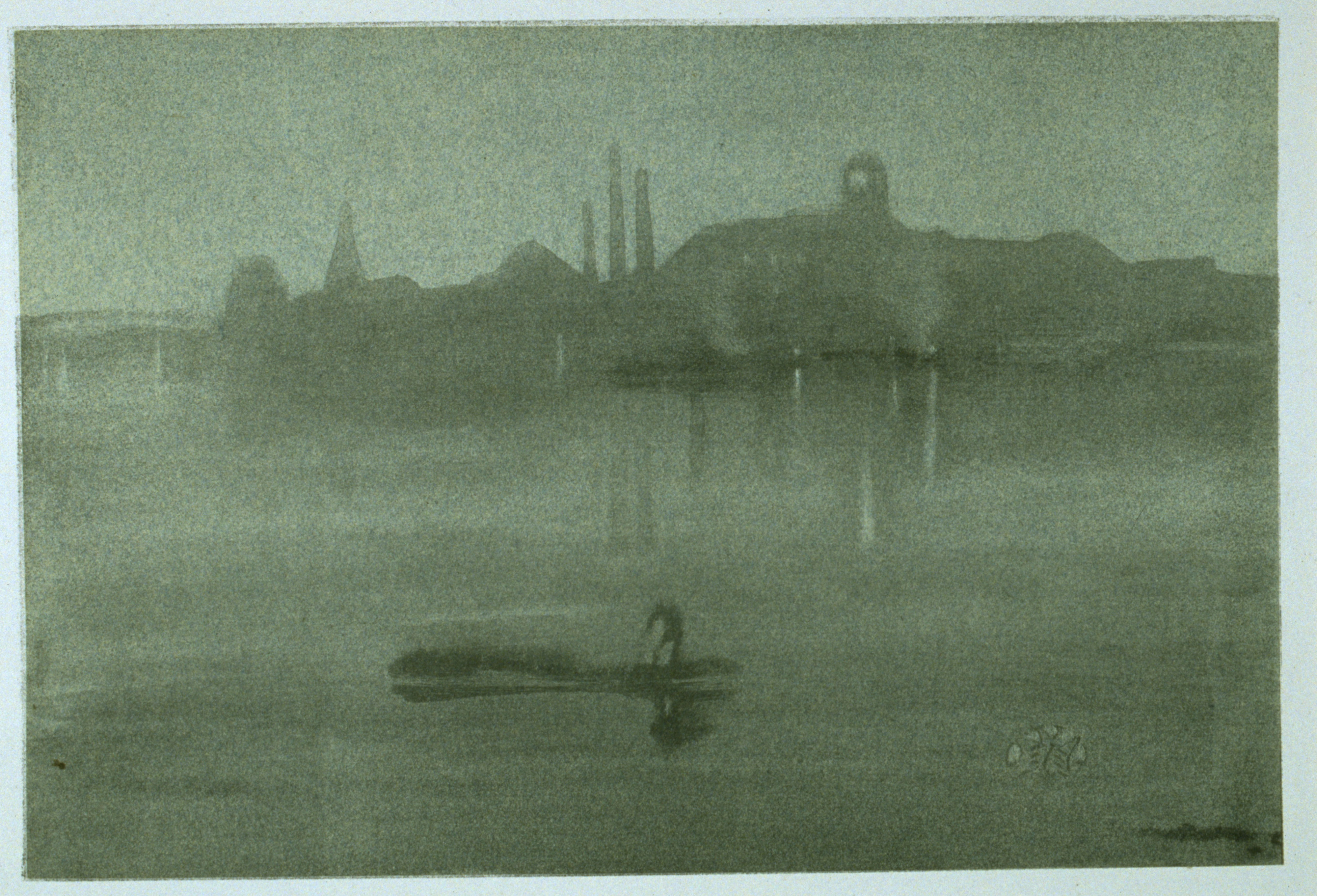

The landscape exhibition features Whistler’s etchings and lithographs from the late 1850s and shows an artist developing his craft, even as his influences remained very clear.

“These works, all from the collection of The Fralin, expose Whistler’s debt to Rembrandt, contemporary French etchers like Charles Meryon, and the work of and pieces found in the collection of Whistler’s brother-in-law, Francis Seymour Haden,” said exhibition curator Emilie Johnson, the museum’s 2012-13 Luzak-Lindner Graduate Fellow.

Artists in the mid-19th century were drawn to the expressive qualities of printmaking, and etching in particular. Whistler’s early prints – the first works he exhibited and made available to the public – explored landscapes and processes of modernization, such as workers installing telegraph lines juxtaposed against an old farm settlement, and scenes of gritty urban life, all subjects popular at the time.

“Evident in these works are Whistler’s emerging mastery of the medium and his evolving interest in the aesthetics of light, tone and shade, which would dominate his later and better-known paintings and prints,” Johnson said. “The first exhibition, on view in the spring, reveals an artist during a period of almost frenzied experimentation and prolific work, the results of which would be a singular, controversial artistic vision.”

The second, portrait-focused exhibition, on view in the summer, considers the various ways Whistler represented people over the course of his career.

As in his landscapes, initially Whistler was heavily influenced by Rembrandt’s etched portraits, especially the dramatic light and shade the Dutch master used to represent the sitter’s personality, Johnson said. “However, as he gained experience with the medium in the late 1850s, his etchings of family members and fellow artists became more personal and increasingly combined truthful representation with an emphasis on the deep, dark shadows that etching could so powerfully display.”

By the 1870s, Whistler’s work had shifted toward an intense focus on the play of light and atmosphere in his compositions. This was as true for his landscapes as his portraits.

“Dramatically cropping his compositions and purposefully obscuring backgrounds left his subjects floating in space, a disjointed appearance Whistler prized and that resolved some of the struggles he had with rendering figures,” Johnson said.

By the 1890s, Whistler had resolved his approach to the body, treating portraits much as he did his other subject matter. Flattened, elongated forms emerge from hazy, indistinct backgrounds, ready to step off the page. The etched and lithographic portraits of the 1870s through the 1890s reveal Whistler’s full artistic integration.

The museum, located at 155 Rugby Road, is open Tuesdays through Sundays, from noon to 5 p.m.

The Fralin Museum of Art’s programming is made possible by the support of The Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation.

The exhibition is made possible through the support of Arts$, Albemarle Magazine and Ivy Publications LLC's Charlottesville Welcome Book.

Media Contact

Article Information

January 24, 2013

/content/becoming-butterfly-landscapes-james-mcneill-whistler-opens-jan-25-fralin-museum-art