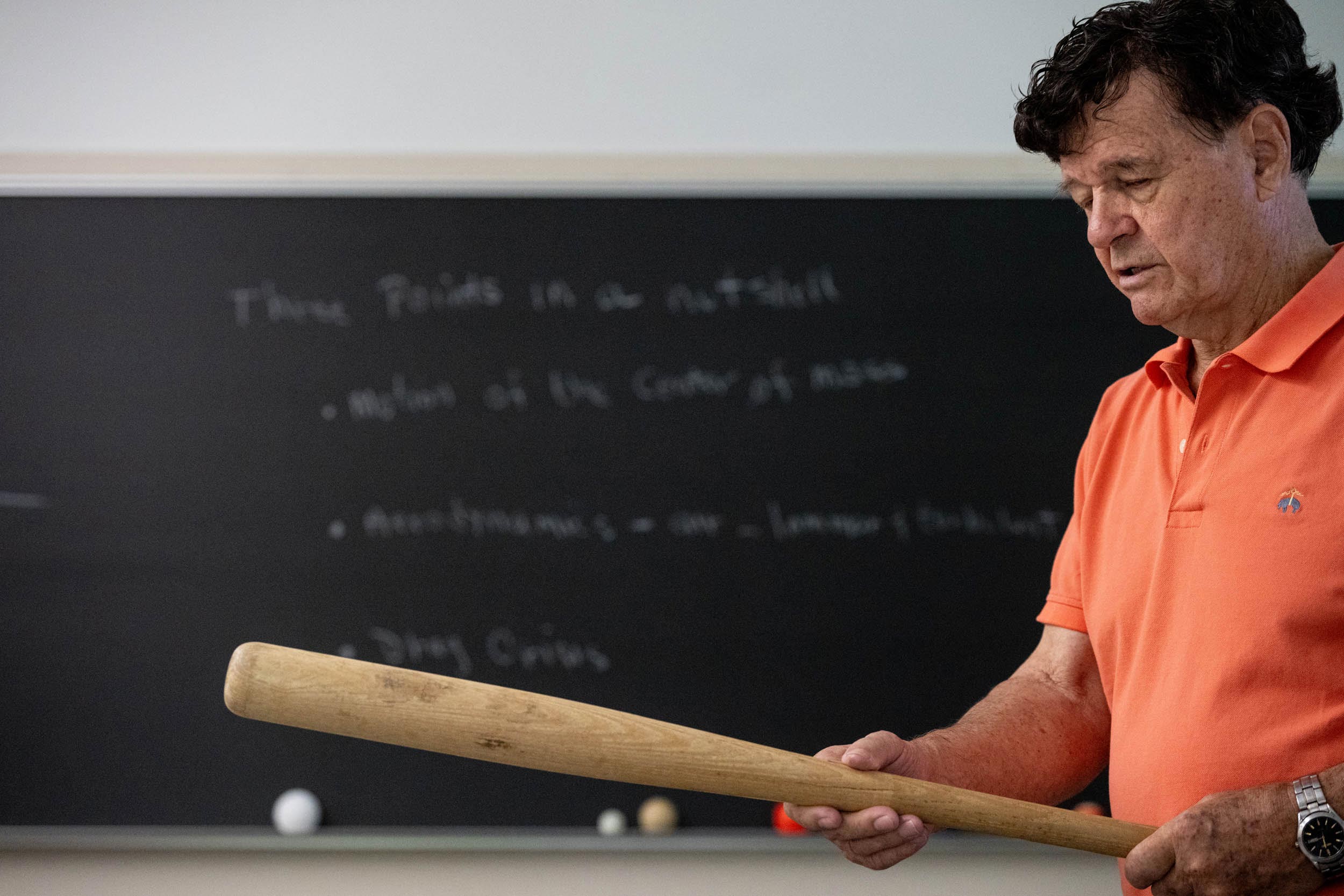

This was Lindgren’s way to explain the center of percussion. In baseball terms, this is the “sweet spot” of the bat, or the location which produces the least vibrational sensation (sting) in the batter’s hands. When the putty is knocked loose, the hands sting. When the putty remains stationary, that represents a good feeling of contact for the batter.

There’s little sting, Lindgren said, because the translation and rotational motion of the end of the bat handle cancel each other out.

“Therefore,” Lindgren said, “the putty feels no force.”

Such an example is just one of many lessons Augustin said he’s taking with him as begins his baseball career with the Cavaliers. The right-hander from New Jersey said he throws five types of pitches and, through Lindgren, he’s learning more about the impact of spin on each one.

“With a curveball, if I get the highest spin on it, it will tumble a lot more,” Augustin said. “But a slider will move left to right more. (Lindgren) has us solve problems that really show how all that works. It’s really cool.”

Beyond the sports they play in, both Augustin and McKneely said they’ve found value in knowing more about the games they see on television.

Lindgren’s course also teaches why golf balls have dimples, why a soccer ball curves, why going low is the best option in blocking and tackling in football and the effects of motion on the cue ball in billiards, among other lessons.

“Usually you watch sports just to watch it because it’s entertaining and you enjoy it,” McKneely said, “but I feel like now I might watch it and be like, ‘Oh, the low man’s winning [in a football pile] because of torque.’

“I just feel like I can apply that a little bit more to when I'm watching sports and be like ‘Yeah, I learned about this. That’s pretty cool.’”