November 12, 2008 — Starting with a question. Jumping out of an airplane without a parachute. Thinking of a higher purpose. Living with doubt. Realizing you can't do it alone. Following a new path of collaboration.

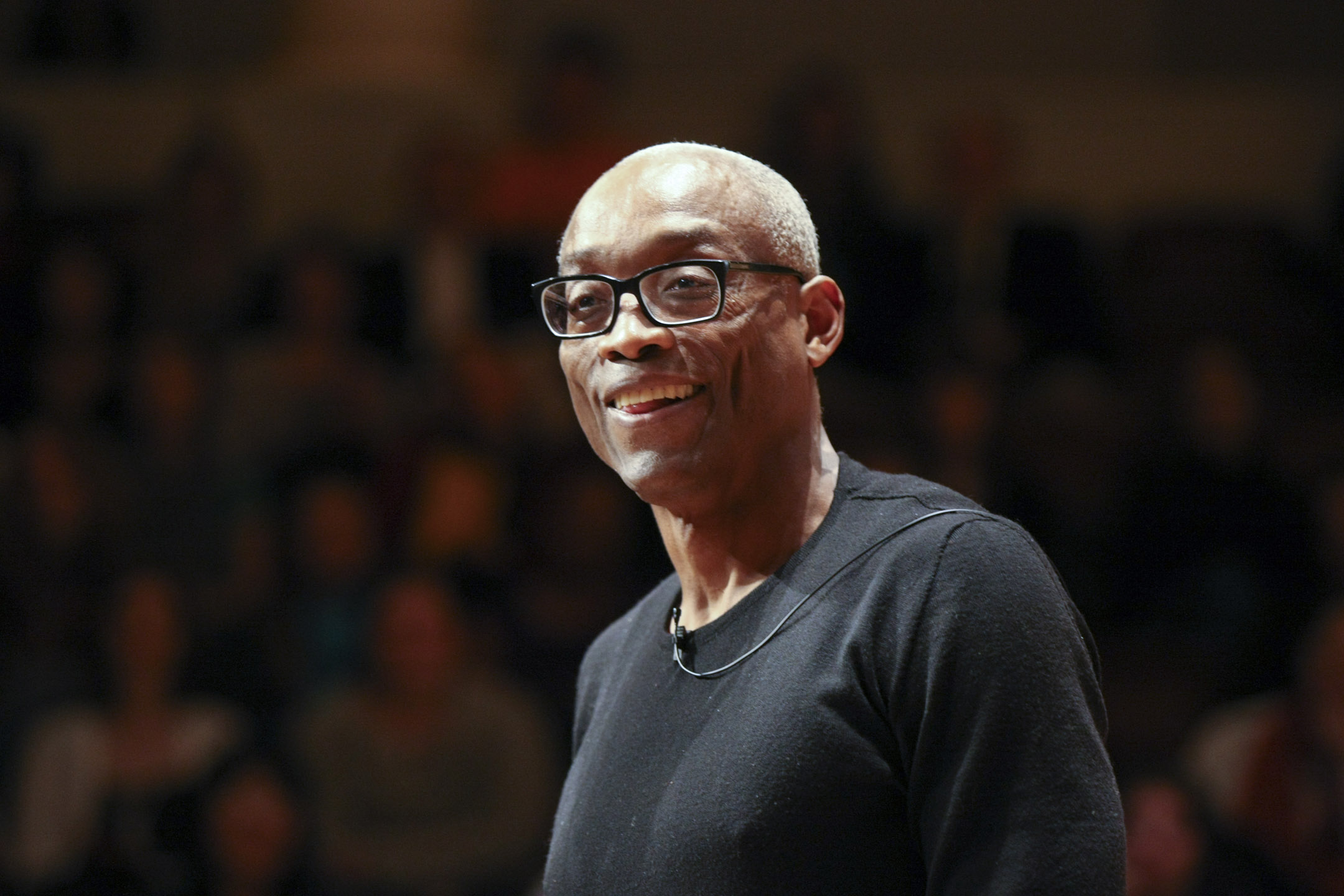

These were the ideas that internationally renowned dancer and choreographer Bill T. Jones discussed as being part of his creed for making art in Sunday's first Assembly for the Arts at the University of Virginia.

A MacArthur Fellow whose work often explores issues of personal identity, form and social commentary, Jones is taking part in a weeklong residency at U.Va. The project he is leading seeks to reconcile the view of Abraham Lincoln that he held as a boy — full of love and hope despite living through the civil rights struggle — with his place in midlife as an artist who admits he is filled with doubt every other day, has gone through periods of feeling lost and sometimes believes in nothing.

"This is a convocation of the various art departments," Jones said. "You're all supposed to be amazingly prescient, daring. There's a wall there and you're going to find a way to rearrange your molecules and go through that wall if you need to. You are supposed to be the ones who go where people are afraid to go and say, 'It's OK, come on.' Or you're supposed to be the one who goes through the darkness and is never heard from again, but you left some little marker that says 'I dare you to come.'"

During his residency, Jones will explore a new major work, "Fondly Do We Hope — Fervently Do We Pray ...," a dance/theater piece that he is creating to premiere at the Ravinia Festival in Chicago in September to commemorate the bicentennial of Abraham Lincoln's birth.

The workshop and exploration component of the project, "100 Migrations," will take place on Grounds, in Charlottesville and in three other cities Jones and his company will visit during a yearlong exploration to create the work.

He said his job as an artist "is to organize various elements into something that maybe connects to you and your father, you and your parents, you and your place in history, you in the act of looking, you in the act of remembering. It would be great if at the end of the week I could do that."

Pointing to the mural on the wall behind the stage in Old Cabell Hall Auditorium, a copy of Raphael's "School of Athens," Jones contrasted the notion of the individual genius — not only Raphael, but also Michelangelo, depicted in the painting — with what he pursues in his art: collaboration.

Jones, the son of migrant workers who formed his dance company in 1982 with his partner and collaborator, the late Arnie Zane, said he starts an art project or it comes to him as a question.

For this commemorative work, Jones asked himself what he needed to say about Lincoln, who already has 15,000 books written about him. In Lincoln's time, everyone was thinking about what emancipation meant; that was the big question. Jones asked the audience to think about what the big questions are in the U.S. today.

He acknowledged that the presidential election of Barack Obama made him reconsider the project, but still left him with the question, "Can we say the Civil War is finally over?"

"No, there's still an undeclared civil war," he said.

What is needed today is a genius public, Jones said. It's not enough to be hopeful today, to say, "Yes, we can" today. Jones said we should ask ourselves whether we're fulfilling that slogan again and again over time.

More specifically, he referred to this week's artistic process: "That's what I want you to do — articulate a big question and then collaborate. … In other words, you can't do it alone."

Jones also compared artistic collaboration to making a successful relationship. He recounted a dancer in the group asking Zane and him how they had such a good relationship.

"My understanding is, first and foremost, you and your partner need a project. You need something that you are both building, that you're doing together. If you have that, there's a good chance that relationship will last," Jones said.

"I think art-making in a collaborative sense is like trying to make a successful relationship. What is it that you want to do? Even more so, what do you think needs to be done?"

Another way to think about making art is to think about how you would react if you were diagnosed with a life-threatening illness. "How do you live? How do you get out of bed everyday? How do you dare love that little one there?

"First of all, you must live in the moment. You must cherish small things. You must make realistic goals and be willing and able to change them. The last one, which is the big challenge now for us, is you must have a higher sense of purpose in life.

"There you have it," said Jones.

Lest he leave the audience with such fuzzy, feel-good notions, Jones acknowledged the doubt an artist has to live with every day.

"Art is not supposed to make those of us who make it feel good," he said.

The virtue of art comes in "when you are in there on the good days and on the bad days and you do it not because somebody is going to say 'Good job,' but you do it because of something internal, something inside. The virtue has to be self-generated and it has to be something that literally is a struggle every day to maintain."

Jones went on to describe the collaborative project he and U.Va. participants are working on.

"What I know about the piece now – it starts as two armies performing maneuvers, then they walk across that bed, circle around the bed, then they disappear," he said. In the middle of the two armies will be a huge bed, Lincoln's deathbed, with a diagonal slash of red where the participants will write out the text of one of Lincoln's speeches. They will walk through the red paint of the words and leave footprints.

"I'm going to give that bed to the community, so the highest aspirations about culture will become a footpath on the man's deathbed. … It will be a visualization of not 1865, but 2008."

These were the ideas that internationally renowned dancer and choreographer Bill T. Jones discussed as being part of his creed for making art in Sunday's first Assembly for the Arts at the University of Virginia.

A MacArthur Fellow whose work often explores issues of personal identity, form and social commentary, Jones is taking part in a weeklong residency at U.Va. The project he is leading seeks to reconcile the view of Abraham Lincoln that he held as a boy — full of love and hope despite living through the civil rights struggle — with his place in midlife as an artist who admits he is filled with doubt every other day, has gone through periods of feeling lost and sometimes believes in nothing.

"This is a convocation of the various art departments," Jones said. "You're all supposed to be amazingly prescient, daring. There's a wall there and you're going to find a way to rearrange your molecules and go through that wall if you need to. You are supposed to be the ones who go where people are afraid to go and say, 'It's OK, come on.' Or you're supposed to be the one who goes through the darkness and is never heard from again, but you left some little marker that says 'I dare you to come.'"

During his residency, Jones will explore a new major work, "Fondly Do We Hope — Fervently Do We Pray ...," a dance/theater piece that he is creating to premiere at the Ravinia Festival in Chicago in September to commemorate the bicentennial of Abraham Lincoln's birth.

The workshop and exploration component of the project, "100 Migrations," will take place on Grounds, in Charlottesville and in three other cities Jones and his company will visit during a yearlong exploration to create the work.

He said his job as an artist "is to organize various elements into something that maybe connects to you and your father, you and your parents, you and your place in history, you in the act of looking, you in the act of remembering. It would be great if at the end of the week I could do that."

Pointing to the mural on the wall behind the stage in Old Cabell Hall Auditorium, a copy of Raphael's "School of Athens," Jones contrasted the notion of the individual genius — not only Raphael, but also Michelangelo, depicted in the painting — with what he pursues in his art: collaboration.

Jones, the son of migrant workers who formed his dance company in 1982 with his partner and collaborator, the late Arnie Zane, said he starts an art project or it comes to him as a question.

For this commemorative work, Jones asked himself what he needed to say about Lincoln, who already has 15,000 books written about him. In Lincoln's time, everyone was thinking about what emancipation meant; that was the big question. Jones asked the audience to think about what the big questions are in the U.S. today.

He acknowledged that the presidential election of Barack Obama made him reconsider the project, but still left him with the question, "Can we say the Civil War is finally over?"

"No, there's still an undeclared civil war," he said.

What is needed today is a genius public, Jones said. It's not enough to be hopeful today, to say, "Yes, we can" today. Jones said we should ask ourselves whether we're fulfilling that slogan again and again over time.

More specifically, he referred to this week's artistic process: "That's what I want you to do — articulate a big question and then collaborate. … In other words, you can't do it alone."

Jones also compared artistic collaboration to making a successful relationship. He recounted a dancer in the group asking Zane and him how they had such a good relationship.

"My understanding is, first and foremost, you and your partner need a project. You need something that you are both building, that you're doing together. If you have that, there's a good chance that relationship will last," Jones said.

"I think art-making in a collaborative sense is like trying to make a successful relationship. What is it that you want to do? Even more so, what do you think needs to be done?"

Another way to think about making art is to think about how you would react if you were diagnosed with a life-threatening illness. "How do you live? How do you get out of bed everyday? How do you dare love that little one there?

"First of all, you must live in the moment. You must cherish small things. You must make realistic goals and be willing and able to change them. The last one, which is the big challenge now for us, is you must have a higher sense of purpose in life.

"There you have it," said Jones.

Lest he leave the audience with such fuzzy, feel-good notions, Jones acknowledged the doubt an artist has to live with every day.

"Art is not supposed to make those of us who make it feel good," he said.

The virtue of art comes in "when you are in there on the good days and on the bad days and you do it not because somebody is going to say 'Good job,' but you do it because of something internal, something inside. The virtue has to be self-generated and it has to be something that literally is a struggle every day to maintain."

Jones went on to describe the collaborative project he and U.Va. participants are working on.

"What I know about the piece now – it starts as two armies performing maneuvers, then they walk across that bed, circle around the bed, then they disappear," he said. In the middle of the two armies will be a huge bed, Lincoln's deathbed, with a diagonal slash of red where the participants will write out the text of one of Lincoln's speeches. They will walk through the red paint of the words and leave footprints.

"I'm going to give that bed to the community, so the highest aspirations about culture will become a footpath on the man's deathbed. … It will be a visualization of not 1865, but 2008."

— By Anne Bromley

Media Contact

Article Information

November 12, 2008

/content/bill-t-jones-discusses-struggles-art-inaugural-assembly-arts