A new study by researchers at the University of Virginia and other institutions has discovered a type of pigment cell in zebrafish that can transform after development into another cell type.

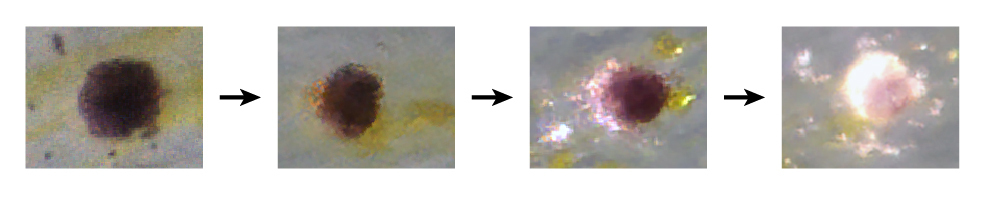

David Parichy, the Pratt-Ivy Foundation Distinguished Professor of Morphogenesis in UVA’s Department of Biology, said that researchers in his lab noticed that some black pigment cells on zebrafish became gray and then eventually white. When they looked closer, they found dramatic changes in gene expression and pigment chemistry.

“We realized that the cells have a secret history hiding in plain sight,” he said. “Zebrafish have been studied closely for more than 30 years – we know a lot about them – but this is the first time this transformation has been noticed. It’s a very surprising discovery.”

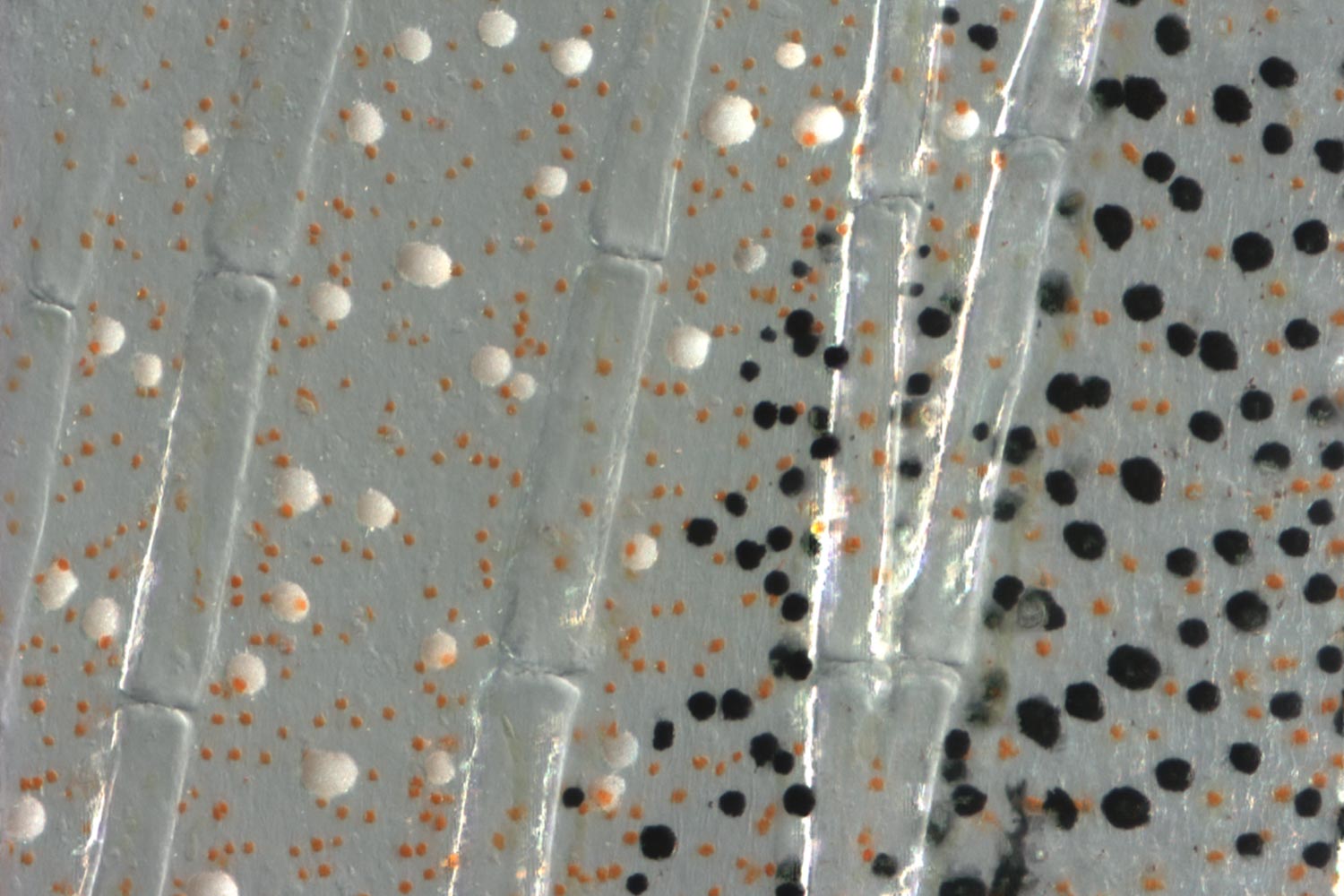

The unique cell population sheds the pigment melanin, changing in color from black to white during the life cycle of an individual fish. These special cells are found at the edges of the fins, where they seem to act as a signal to other zebrafish.

Cells transforming from black to white. (Contributed photo)

The ability of a developed cell to differentiate directly into another type of cell is exceptionally rare. Normally such a change requires experimental intervention, returning the cell to a stem-cell state in a dish, before it can differentiate, or transform, as something else.

The new finding, published recently online in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggests that some developed cells might be more amenable to change than generally believed.

“For a long time, the idea in developmental biology has been that once a cell has completed its development, it stays that way,” said Parichy, who led the study. “We are discovering that this is not always the case; that, in fact, there are some rare cell populations that are able to change into something new even after their initial development. The dogma says this isn’t supposed to happen.”

Study leader David Parichy, the Pratt-Ivy Foundation Distinguished Professor of Morphogenesis in UVA’s Department of Biology. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

Stem cells develop into one type of cell or another, and then those differentiated cells normally stay that way – a skin cell stays a skin cell, muscle cells stay muscle, and so on. But the newly discovered cells, called melanocytes, which are similar to those of humans, contain melanin initially, then lose it and make a white pigment in its place. These cells block the molecular pathways that otherwise would allow them to make melanin and turn on new genes required for their new appearance.

“We are discovering that … there are some rare cell populations that are able to change into something new even after their initial development. The dogma says this isn’t supposed to happen.”

- David Parichy

This ability to change makes the cells a good study model for understanding both how cells differentiate, and how it may be possible to make cells differentiate into something new even while still in the animal.

The discovery, Parichy said, has possible implications for regenerative medicine, where researchers might want to use cells already present to make replacement tissues of various cell types. Such a capability could be useful in treating patients after stroke, spinal cord injury, heart attacks or other trauma.

“Knowing how cells can be made to change their differentiated state is essential to regenerative medicine, so having an example in which a species does this naturally is very valuable,” he said.

Researchers already are using stem cells to create various cell types, from muscle to skin, but perhaps developed cells also could play a role. Parichy hopes that what he and other researchers learn from the highly unusual transformation of these pigment cells will provide greater understanding of the process and, perhaps, how to manipulate it by reprogramming cells.

“If we can understand how cells go from black to white, this has implications for helping us better understand cells more generally,” he said.

The study also showed that zebrafish were able to recognize whether or not these transforming cells were present, and this affected their social interactions. The cells are located at the fin tips, which are flared during social interactions, like “raising a flag.” As such, these black cells that turn to white may affect associations of fish in the wild, with consequences for access to food and mates, as well as avoidance of predators.

Remarkably the authors also found an additional population of white cells in zebrafish, made in a different way, and that different species of the fish had different complements of these populations. Parichy noted that the study “really shows how much you can learn by tackling questions at levels ranging from genes to cells to behavior to evolution.”

Biology Ph.D. candidate Vic Lewis served as the lead author on the study, and assistant professor of biology Tracy Larson also contributed.

Media Contact

Article Information

June 5, 2019

/content/biologists-discovery-may-advance-regenerative-medicine