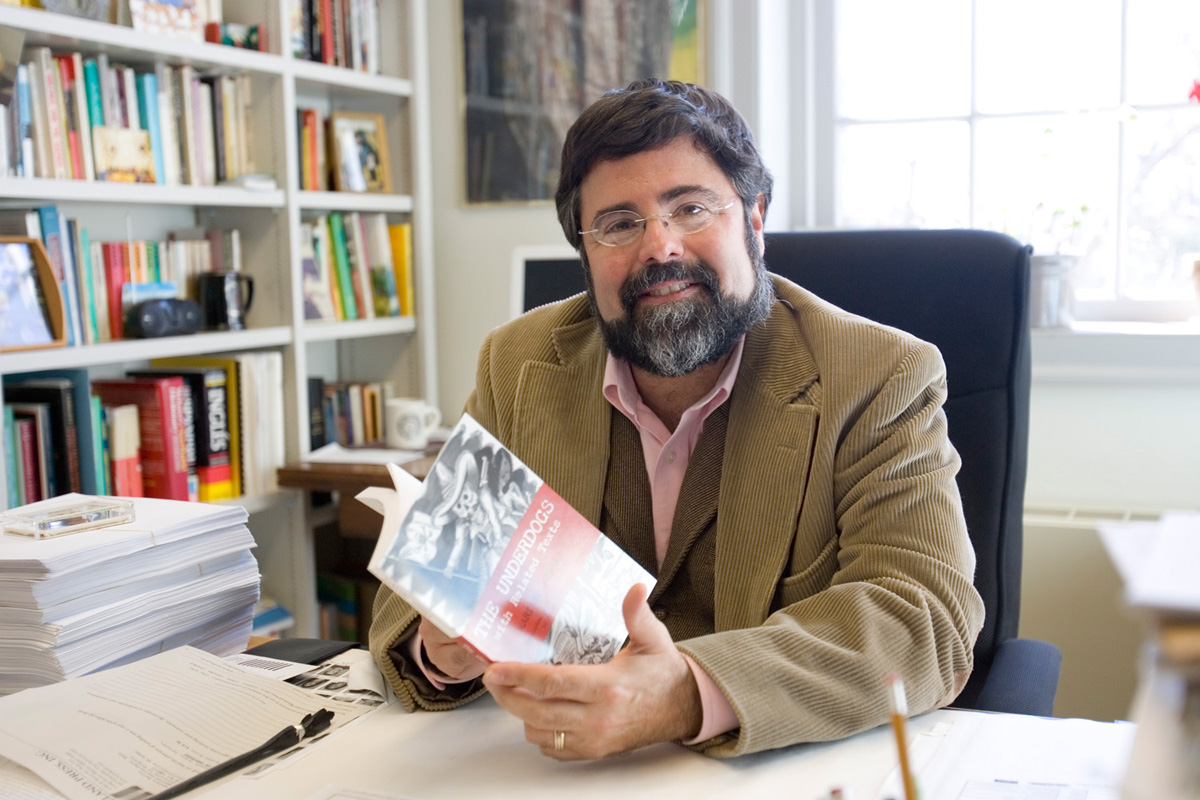

Dec. 4, 2006 -- Gustavo Pellón has dedicated his life to bridging two cultures — combining his Spanish heritage as a native of Cuba with life in the United States, where he has lived since age 10. With his latest project, the translation of the iconic novel of the Mexican Revolution, Pellón has again brought these worlds together in a way that he hopes will increase understanding of Latin America in his adopted homeland.

As a child, Pellón embraced U.S. culture, even winning English language awards in school. But as he approached adulthood he knew he didn’t want to forget his heritage and language. His choice to become a professor of Latin American and comparative literature was his way of bridging the two worlds in which he lives.

When asked to translate “The Underdogs: Pictures and Scenes from the Present Revolution,” Mariano Azuela’s seminal account of the Mexican Revolution, Pellón described it as the happiest day of his professional life.

According to Pellón the novel has broad appeal. It is a favorite of not only Latin American literature professors but also is used extensively in history courses, as well as in world and comparative literature classes.

“It’s the most famous work to come out of the 1910 revolution. It’s impossible not to include it if one is doing a course on Mexican history,” Pellón said.

Pellón approached the translation with care. His goal was to create a literary equivalent to Azuela’s novel. Pellón’s is the fifth translation of the novel since its initial publication as a serial in the newspaper El Paso del Norte in 1915. The four earlier translations, although valuable as cultural and historical views of how readers in the United States read the novel at that particular time, deviated from the author’s “spare and unsparing, very brutal style, which is an important aspect of Azuela’s revolutionary style,” Pellón said. One translator added profanity to contemporize the dialogue, and two others liberally paraphrased.

“Ideologically you cannot be loose with the text. You cannot improve or bring it up to date,” Pellón said.

With his deep understanding of history, comparative literature, Spanish and English languages and the cultures in Mexico and the United States, Pellón approached the novel both from the historical perspective of the revolution and as a literary work. He knows the novel intimately and has taught it for many years in his Latin American literature classes. Adhering to his belief that it is necessary to balance making the text accessible to contemporary readers while keeping faithful to the author’s creation, Pellón was able to create a translation that accurately reflects the original text in tone and intention.

Pellón always kept in mind the modern reader as he approached the translation, particularly the dialogue, which comprises the bulk of the novel and is part of its revolutionary literary aspect. In the United States, many Spanish words are common and part of everyday speech, Pellón said. He looked to Cormac McCarthy’s “Border Trilogy” as a model that blends English and Spanish. Aware of this aspect of today’s culture, he left many familiar words in Spanish. One example he cited is when Azuela refers to a character as El loco, which means the crazy one. Pellón left the Spanish reference in the translation rather than translate it.

The novel’s literary significance lies in its bridging the styles of the 19th and 20th centuries. Azuela was a doctor and novelist who served as a colonel in Pancho Villa’s army. He observed firsthand the events he chronicled in the story and was able to create a realistic novel that influenced and was admired by 20th century Latin American writers, Pellón said.

Azuela’s descriptions of the landscape represent the flowery lyrical 19th century style that looked outward to the exotic and describes the jewel-like qualities of nature. This is contrasted in the text with the spare, linguistic realism of the character’s dialogue. “The novel helps define a watershed moment in the history of modern Mexico in the imagination of the people and helped in the fashioning of their national identity,” Pellón said.

Pellón’s intention was to create a work that is classroom friendly and accessible to the general reader. To help place the book in historical and literary context, Pellón includes invaluable materials in addition to the translation, including chronologies of Azuela’s life and the Mexican Revolution, maps of the path the revolutionaries followed in the book, an historical and literary appendix, recommended readings, a glossary of Spanish terms as well as related texts. Included in the materials are excerpts from “Insurgent Mexico” by newspaper journalist John Reed, who was embedded with the revolutionary troops, reviews of earlier translations and selections from Anita Brenner’s “Idols Behind Altars: Modern Mexican Art and Its Cultural Roots.”

Pellón plans to use the book in a spring class, “Fiction of the Americas,” which will “study the centuries-long ‘conversation’ between North American and Spanish-American writers,” he said.

The class is one of the College’s new second-year seminars.

In some way, Pellón hopes that the book contributes to the U.S. community becoming more comfortable with the border. “I have done something that I hope will broaden knowledge of Latin

American culture in this country,” he said.

COLLEGE OFFERS INAUGURAL SECOND-YEAR SEMINARS

This spring, the College of Arts & Sciences will offer eight second-year seminars. The new initiative is designed to provide second-year students classes that facilitate faculty/student interaction and support the University’s commitment to the undergraduate experience. Classes are limited to 18 students and are being led by some of the College’s best tenured professors who have agreed to take on the teaching assignment in addition to their regular class load.

Courses are being offered in anthropology, studio art, biology, environmental sciences, American politics, comparative politics and comparative literature.

The small class size allows second-year students,whose classes are generally large lectures, to learn in a seminar environment. Classes are not limited to those enrolled in the College but are open to all second-year students on Grounds.

Although not a requirement for enrolling in a class, for some it may be a way to explore an area they are considering as a major and to delve more deeply into the discipline and explore the possibility of having the faculty member as an adviser.

The pilot program is the result of discussions with students,faculty and parents and

is funded by the Parents Committee.

As a child, Pellón embraced U.S. culture, even winning English language awards in school. But as he approached adulthood he knew he didn’t want to forget his heritage and language. His choice to become a professor of Latin American and comparative literature was his way of bridging the two worlds in which he lives.

When asked to translate “The Underdogs: Pictures and Scenes from the Present Revolution,” Mariano Azuela’s seminal account of the Mexican Revolution, Pellón described it as the happiest day of his professional life.

According to Pellón the novel has broad appeal. It is a favorite of not only Latin American literature professors but also is used extensively in history courses, as well as in world and comparative literature classes.

“It’s the most famous work to come out of the 1910 revolution. It’s impossible not to include it if one is doing a course on Mexican history,” Pellón said.

Pellón approached the translation with care. His goal was to create a literary equivalent to Azuela’s novel. Pellón’s is the fifth translation of the novel since its initial publication as a serial in the newspaper El Paso del Norte in 1915. The four earlier translations, although valuable as cultural and historical views of how readers in the United States read the novel at that particular time, deviated from the author’s “spare and unsparing, very brutal style, which is an important aspect of Azuela’s revolutionary style,” Pellón said. One translator added profanity to contemporize the dialogue, and two others liberally paraphrased.

“Ideologically you cannot be loose with the text. You cannot improve or bring it up to date,” Pellón said.

With his deep understanding of history, comparative literature, Spanish and English languages and the cultures in Mexico and the United States, Pellón approached the novel both from the historical perspective of the revolution and as a literary work. He knows the novel intimately and has taught it for many years in his Latin American literature classes. Adhering to his belief that it is necessary to balance making the text accessible to contemporary readers while keeping faithful to the author’s creation, Pellón was able to create a translation that accurately reflects the original text in tone and intention.

Pellón always kept in mind the modern reader as he approached the translation, particularly the dialogue, which comprises the bulk of the novel and is part of its revolutionary literary aspect. In the United States, many Spanish words are common and part of everyday speech, Pellón said. He looked to Cormac McCarthy’s “Border Trilogy” as a model that blends English and Spanish. Aware of this aspect of today’s culture, he left many familiar words in Spanish. One example he cited is when Azuela refers to a character as El loco, which means the crazy one. Pellón left the Spanish reference in the translation rather than translate it.

The novel’s literary significance lies in its bridging the styles of the 19th and 20th centuries. Azuela was a doctor and novelist who served as a colonel in Pancho Villa’s army. He observed firsthand the events he chronicled in the story and was able to create a realistic novel that influenced and was admired by 20th century Latin American writers, Pellón said.

Azuela’s descriptions of the landscape represent the flowery lyrical 19th century style that looked outward to the exotic and describes the jewel-like qualities of nature. This is contrasted in the text with the spare, linguistic realism of the character’s dialogue. “The novel helps define a watershed moment in the history of modern Mexico in the imagination of the people and helped in the fashioning of their national identity,” Pellón said.

Pellón’s intention was to create a work that is classroom friendly and accessible to the general reader. To help place the book in historical and literary context, Pellón includes invaluable materials in addition to the translation, including chronologies of Azuela’s life and the Mexican Revolution, maps of the path the revolutionaries followed in the book, an historical and literary appendix, recommended readings, a glossary of Spanish terms as well as related texts. Included in the materials are excerpts from “Insurgent Mexico” by newspaper journalist John Reed, who was embedded with the revolutionary troops, reviews of earlier translations and selections from Anita Brenner’s “Idols Behind Altars: Modern Mexican Art and Its Cultural Roots.”

Pellón plans to use the book in a spring class, “Fiction of the Americas,” which will “study the centuries-long ‘conversation’ between North American and Spanish-American writers,” he said.

The class is one of the College’s new second-year seminars.

In some way, Pellón hopes that the book contributes to the U.S. community becoming more comfortable with the border. “I have done something that I hope will broaden knowledge of Latin

American culture in this country,” he said.

COLLEGE OFFERS INAUGURAL SECOND-YEAR SEMINARS

This spring, the College of Arts & Sciences will offer eight second-year seminars. The new initiative is designed to provide second-year students classes that facilitate faculty/student interaction and support the University’s commitment to the undergraduate experience. Classes are limited to 18 students and are being led by some of the College’s best tenured professors who have agreed to take on the teaching assignment in addition to their regular class load.

Courses are being offered in anthropology, studio art, biology, environmental sciences, American politics, comparative politics and comparative literature.

The small class size allows second-year students,whose classes are generally large lectures, to learn in a seminar environment. Classes are not limited to those enrolled in the College but are open to all second-year students on Grounds.

Although not a requirement for enrolling in a class, for some it may be a way to explore an area they are considering as a major and to delve more deeply into the discipline and explore the possibility of having the faculty member as an adviser.

The pilot program is the result of discussions with students,faculty and parents and

is funded by the Parents Committee.

Media Contact

Article Information

December 4, 2006

/content/bridging-two-worlds-gustavo-pellon-translates-seminal-work-mexican-revolution