February 15, 2010 — Last summer, Guoqing Zhang, a chemistry doctoral student at the University of Virginia, was experimenting with a simple sunscreen compound when he made a startling discovery. As he crushed some crystals under an ultraviolet lamp, the green-blue-emitting material suddenly glowed yellow.

His curiosity led him to smear the sunscreen material onto a sheet of weighing paper, and the compound glowed there, too. When smeared, it is yellow. After waiting a few minutes or heating it for a few seconds, it turned green-blue. When he scratched it again, the scratched regions became yellow again. He did not know what he was seeing, but he had never seen it before.

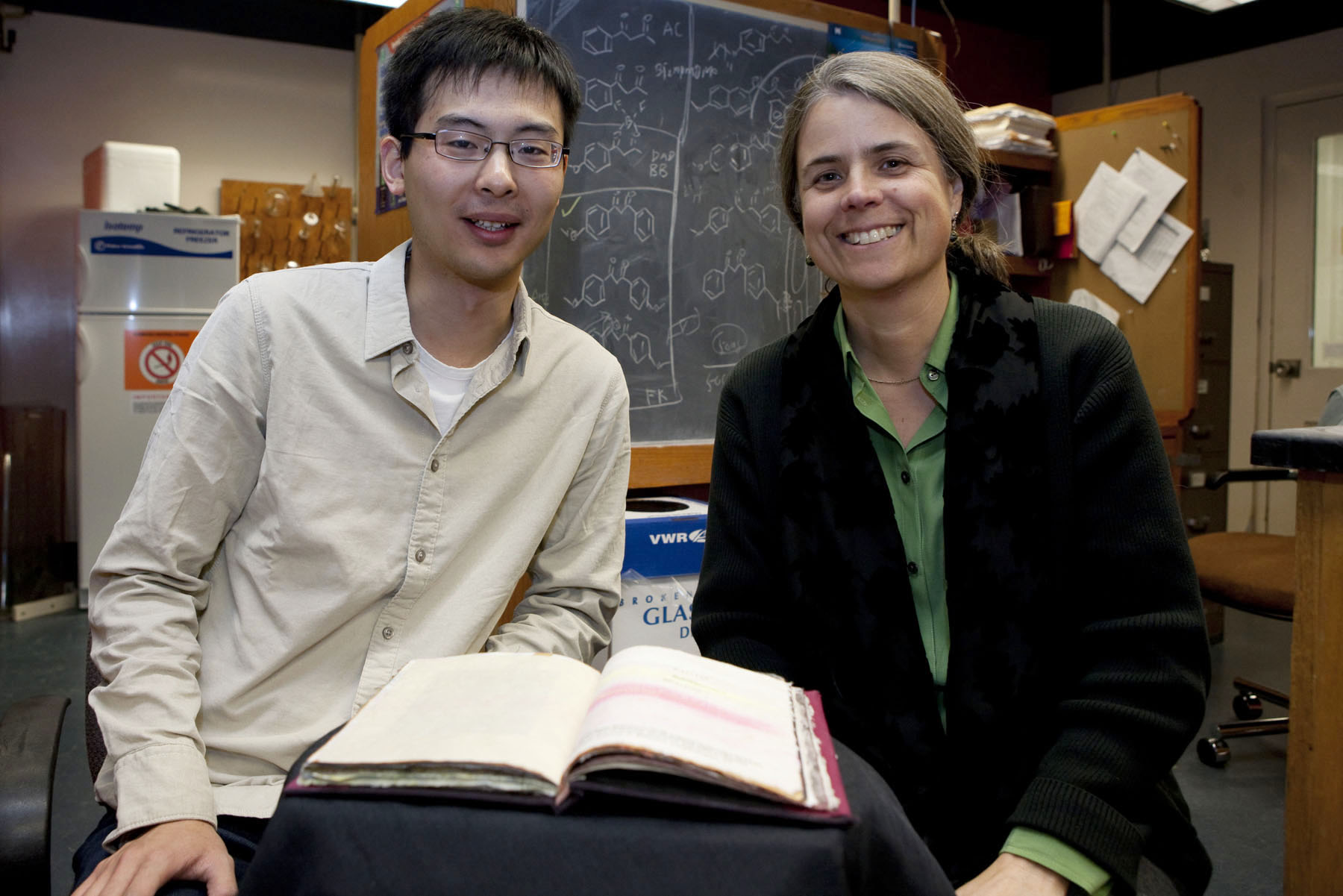

He hurried to tell his adviser, chemistry professor Cassandra Fraser. "You've got to see this!" he said.

She, too, was amazed. They started playing with the compound, watching the color become yellow each time they scratched the surface of the material and fade back to green-blue again.

"It's self-healing," Fraser said. "It can be written and re-written." In art, this kind of fading or ephemeral quality is called "fugitive," but what is amazing here is that the effect is also regenerative.

They have since tested other dyes and have created other color combinations, and they also have developed methods for "fixing" the colors for varying lengths of time. They even have a way to create a negative image; that is, a material that turns dark in scratched regions.

This had to lead to other things, and so it has.

Fraser and Zhang reached out to collaborators across Grounds, in the business community and at other universities. Today, they are working with visual artists and materials engineers, business partners and even high school students to imagine the possibilities for their very visual discovery. They even started a new company, Luminesco, with the idea that these compounds could be used as high-tech "mechanosensors" and possibly in forensic and security applications. They also envision uses as rewritable surfaces, a new art medium and possibly as a creative tool for children.

"So many people have been brought together by this amazing fluorescent molecule," Zhang said.

This month, Fraser and Zhang published a paper about their finding in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, and an important follow-up study is under review in Inorganic Chemistry.

Fraser has long viewed chemistry as one captivating facet of her many interests. In college, she nearly majored in art and was always as drawn to paintbrushes and palettes of colors as she was to test tubes and colorful chemicals. She earned a master's degree in theology from Harvard Divinity School before earning her doctorate in chemistry from the University of Chicago. Today she is a synthetic chemist with an interest in biomedicine and sustainable design, and color continues to figure prominently.

"My dream has always been to integrate the arts and sciences," she said.

She is, in fact, an enthusiastic participant in U.Va.'s Arts and Sciences Project, supported and encouraged by the Office of the Vice President for Research. The idea is to bring together creative minds from across the disciplines to generate new ideas unbound by the restraints of traditional domains.

Zhang is one of those creative minds. A native of Xinxiang, China, he brings a sense of innovation and play to fundamental discovery, always looking for something new, even when he does not yet understand what he is uncovering.

"Guoqing is a cowboy chemist," Fraser said. "He's is always traveling the frontiers, and doing things his own crazy, unconventional way. He finds the extraordinary in the very simple and ordinary, and intuits the possibilities 10 steps ahead of what he can even put into words. That's why he's always discovering things. Sometimes I have to say, 'OK, great that you've found this, but now let's turn it into science.'"

The science, funded by the National Science Foundation, is focused on synthesizing and fabricating light-emitting biomaterials and chemicals, and from these fundamental, exploratory efforts have emerged a variety of practical uses.

Earlier this year, Fraser and Zhang developed a new material that simplifies the imaging of oxygen-deficient regions of tumors and other tissues. Cancer researchers at U.Va.'s Cancer Center and at Duke University Medical Center are now testing that material.

And Fraser and Zhang are devoted to creating cost-effective and safe materials that are biorenewable and sustainable with little negative effect on the environment.

The two researchers are collaborators, every bit as much as they are student and mentor.

Their new light-emitting material has drawn the interest and collaboration of visual artist and printmaker Dean Dass, associate chair for studio art in the McIntire Department of Art.

"This material has nearly miraculous properties," he said. "It really seems to be 'self-healing,' as Cassandra poetically describes it.

"Normally in artistic use, pigments that fade are considered 'fugitive' and must be avoided. This property in these pigments redefines that notion as the pigments seem to return to their original condition over and again," he said. "The possibilities for the sheer visual wonder of this are endless. And when applied to, say, the environment, the question of 'fugitive' or 'self-healing' is also an interesting ethical question. It can redefine the nature of our use of materials as something other than permanent or unalterable. Countless artists working today, and even many of our own art students, would like to think of their aesthetic in this engaged and relational way."

Dass was so impressed with the glowing compounds, he devoted a few pages to them in a collaborative book published in the U.Va. printmaking programs last fall. Post-baccalaureate student Rachel Singel supervised the project, and other faculty and students contributed. The book, "Time," was inspired by the writings of Jorge Luis Borges and his concepts of space and time. Fraser and Zhang were included as co-authors.

Berenika Boberska, a visiting artist to U.Va. from Poland who has organized an interdisciplinary team of artists, architects, engineers and scientists for the Fallow City project, has even considered incorporating the glowing dye synthesized by Zhang and Fraser.

"Artists and chemists actually have a shared love for materials," Fraser said. "It's a natural fit."

Fraser and Zhang shared their discovery with a high school chemistry class from St. Anne's-Belfield School in Charlottesville. During a recent visit, students were so awed by the glowing transcendent nature of the material and the drawings they were able to create, they did not want to leave Fraser's lab.

"Our students were able to see a real lab and actual research in action," said St. Anne's chemistry teacher Meg Van Liew, who has twice brought classes to Fraser's lab. "Plus, the material they are working with is visually cool and really excites students who are looking for science beyond the textbooks."

Van Liew noted that her students were pleased to see that undergraduate students also participate in research in Fraser's lab, demonstrating that there are research opportunities at the undergraduate level.

"Cassandra is a really enthusiastic teacher who makes the lab a fun and stimulating place," Van Liew said.

His curiosity led him to smear the sunscreen material onto a sheet of weighing paper, and the compound glowed there, too. When smeared, it is yellow. After waiting a few minutes or heating it for a few seconds, it turned green-blue. When he scratched it again, the scratched regions became yellow again. He did not know what he was seeing, but he had never seen it before.

He hurried to tell his adviser, chemistry professor Cassandra Fraser. "You've got to see this!" he said.

She, too, was amazed. They started playing with the compound, watching the color become yellow each time they scratched the surface of the material and fade back to green-blue again.

"It's self-healing," Fraser said. "It can be written and re-written." In art, this kind of fading or ephemeral quality is called "fugitive," but what is amazing here is that the effect is also regenerative.

They have since tested other dyes and have created other color combinations, and they also have developed methods for "fixing" the colors for varying lengths of time. They even have a way to create a negative image; that is, a material that turns dark in scratched regions.

This had to lead to other things, and so it has.

Fraser and Zhang reached out to collaborators across Grounds, in the business community and at other universities. Today, they are working with visual artists and materials engineers, business partners and even high school students to imagine the possibilities for their very visual discovery. They even started a new company, Luminesco, with the idea that these compounds could be used as high-tech "mechanosensors" and possibly in forensic and security applications. They also envision uses as rewritable surfaces, a new art medium and possibly as a creative tool for children.

"So many people have been brought together by this amazing fluorescent molecule," Zhang said.

This month, Fraser and Zhang published a paper about their finding in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, and an important follow-up study is under review in Inorganic Chemistry.

Fraser has long viewed chemistry as one captivating facet of her many interests. In college, she nearly majored in art and was always as drawn to paintbrushes and palettes of colors as she was to test tubes and colorful chemicals. She earned a master's degree in theology from Harvard Divinity School before earning her doctorate in chemistry from the University of Chicago. Today she is a synthetic chemist with an interest in biomedicine and sustainable design, and color continues to figure prominently.

"My dream has always been to integrate the arts and sciences," she said.

She is, in fact, an enthusiastic participant in U.Va.'s Arts and Sciences Project, supported and encouraged by the Office of the Vice President for Research. The idea is to bring together creative minds from across the disciplines to generate new ideas unbound by the restraints of traditional domains.

Zhang is one of those creative minds. A native of Xinxiang, China, he brings a sense of innovation and play to fundamental discovery, always looking for something new, even when he does not yet understand what he is uncovering.

"Guoqing is a cowboy chemist," Fraser said. "He's is always traveling the frontiers, and doing things his own crazy, unconventional way. He finds the extraordinary in the very simple and ordinary, and intuits the possibilities 10 steps ahead of what he can even put into words. That's why he's always discovering things. Sometimes I have to say, 'OK, great that you've found this, but now let's turn it into science.'"

The science, funded by the National Science Foundation, is focused on synthesizing and fabricating light-emitting biomaterials and chemicals, and from these fundamental, exploratory efforts have emerged a variety of practical uses.

Earlier this year, Fraser and Zhang developed a new material that simplifies the imaging of oxygen-deficient regions of tumors and other tissues. Cancer researchers at U.Va.'s Cancer Center and at Duke University Medical Center are now testing that material.

And Fraser and Zhang are devoted to creating cost-effective and safe materials that are biorenewable and sustainable with little negative effect on the environment.

The two researchers are collaborators, every bit as much as they are student and mentor.

Their new light-emitting material has drawn the interest and collaboration of visual artist and printmaker Dean Dass, associate chair for studio art in the McIntire Department of Art.

"This material has nearly miraculous properties," he said. "It really seems to be 'self-healing,' as Cassandra poetically describes it.

"Normally in artistic use, pigments that fade are considered 'fugitive' and must be avoided. This property in these pigments redefines that notion as the pigments seem to return to their original condition over and again," he said. "The possibilities for the sheer visual wonder of this are endless. And when applied to, say, the environment, the question of 'fugitive' or 'self-healing' is also an interesting ethical question. It can redefine the nature of our use of materials as something other than permanent or unalterable. Countless artists working today, and even many of our own art students, would like to think of their aesthetic in this engaged and relational way."

Dass was so impressed with the glowing compounds, he devoted a few pages to them in a collaborative book published in the U.Va. printmaking programs last fall. Post-baccalaureate student Rachel Singel supervised the project, and other faculty and students contributed. The book, "Time," was inspired by the writings of Jorge Luis Borges and his concepts of space and time. Fraser and Zhang were included as co-authors.

Berenika Boberska, a visiting artist to U.Va. from Poland who has organized an interdisciplinary team of artists, architects, engineers and scientists for the Fallow City project, has even considered incorporating the glowing dye synthesized by Zhang and Fraser.

"Artists and chemists actually have a shared love for materials," Fraser said. "It's a natural fit."

Fraser and Zhang shared their discovery with a high school chemistry class from St. Anne's-Belfield School in Charlottesville. During a recent visit, students were so awed by the glowing transcendent nature of the material and the drawings they were able to create, they did not want to leave Fraser's lab.

"Our students were able to see a real lab and actual research in action," said St. Anne's chemistry teacher Meg Van Liew, who has twice brought classes to Fraser's lab. "Plus, the material they are working with is visually cool and really excites students who are looking for science beyond the textbooks."

Van Liew noted that her students were pleased to see that undergraduate students also participate in research in Fraser's lab, demonstrating that there are research opportunities at the undergraduate level.

"Cassandra is a really enthusiastic teacher who makes the lab a fun and stimulating place," Van Liew said.

— By Fariss Samarrai

Media Contact

Article Information

February 15, 2010

/content/chemists-discover-light-emitting-compound-create-collaborations