While teacher turnover is a longtime problem in child care, new data shows that since COVID-19 began, centers’ inability to keep or hire teachers has led many to turn families away.

“Teacher turnover before the pandemic was already an issue,” University of Virginia early childhood education expert Daphna Bassok said. “But since the onset of COVID, the magnitude of the problem has really grown.”

Bassok, Batten Bicentennial Associate Professor of Early Childhood Education at the School of Education and Human Development and Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy, is the associate director of the EdPolicyWorks research center and leads the Study of Early Education Through Partnerships. She said teacher shortages are so pronounced that early childhood education centers across the nation cannot serve the children and families they once did.

“It’s no longer just that turnover is compromising program quality,” Bassok said. “Center directors are saying they have to shut down classrooms or have long waitlists. The shortages and the teacher issues are so pronounced that centers literally cannot run. They can’t keep serving families that they would like to serve, because they can’t find people to work there.”

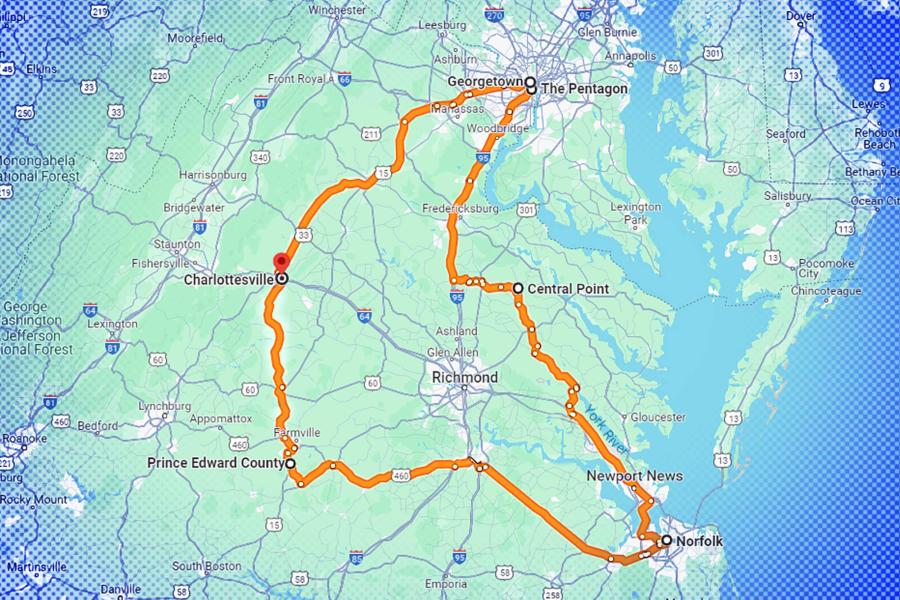

Studies published by Bassok and her team tell the story of the immense struggles to staff child care centers prior to and during the pandemic.

Recent data from Virginia shows that two-thirds of the publicly funded child care sites reported turning families away due to staffing problems, and nearly half indicated they closed down classrooms. During the pandemic, 92% of those surveyed in Virginia reported difficulties staffing their sites.

“Our findings suggest that the children most in need of stable, engaging care and education are the ones most likely to access sites that are understaffed and struggling to meet families’ needs,” Bassok said.