Last summer, Tim Davis opened one of his first workshops for University of Virginia athletic coaches with a moment of vulnerability.

Over Zoom, he held up a photograph of himself in high school raising the Ohio state soccer championship trophy. “Then I shared what was really going on in my mind at that moment – which was shame,” Davis said.

With the score at 0-0 and seven minutes remaining, Davis had missed a critical shot on goal after a beautiful pass from a teammate. His coach pulled him from the game.

“We went on to win in thrilling fashion with me on the bench,” said Davis, an associate professor of public policy in UVA’s Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy. “I was more demoralized by that than excited that we won.”

By sharing the experience with the coaches in his course, he was essentially telling them, “I’m not going to pose here for you,” Davis said. “I’m going to tell you about the real Tim, and I hope you’ll take me up on the offer to tell me about the real you, as a coach and as a person.”

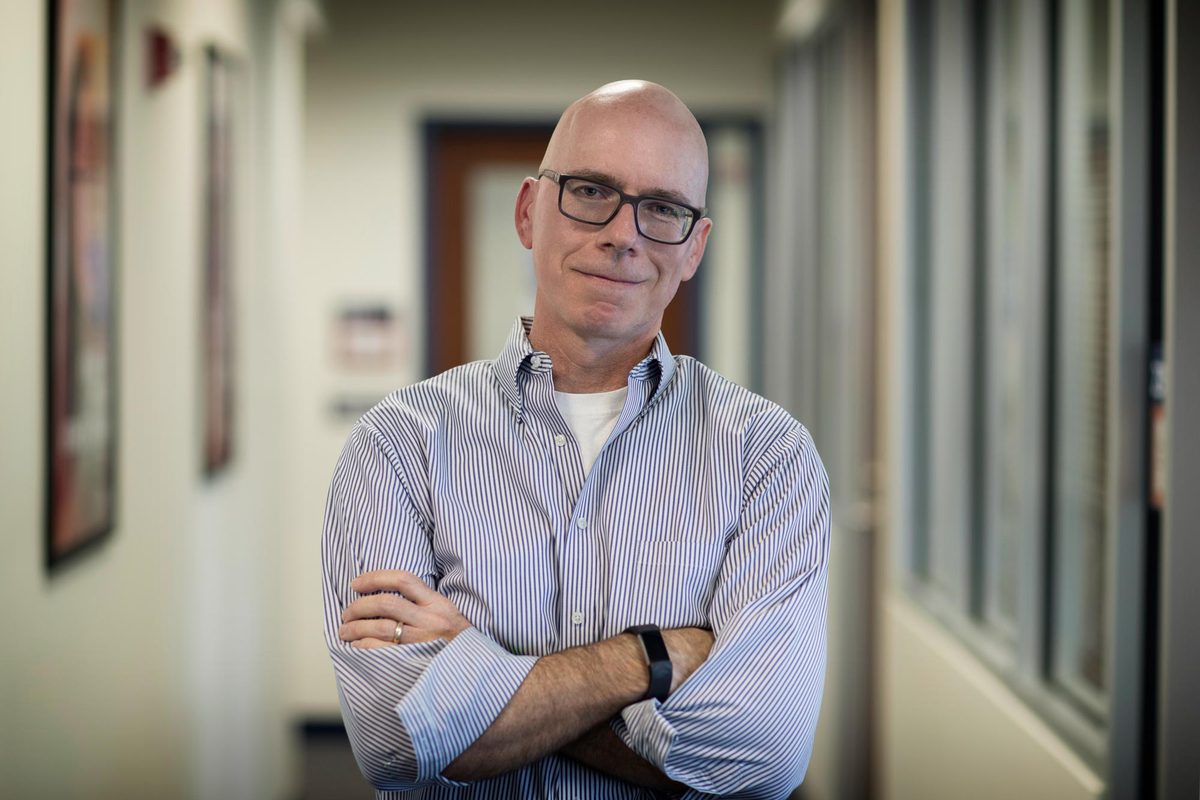

Tim Davis is an associate professor of public policy and clinical psychologist who studies team leadership and emotional resilience. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

A clinical psychologist who studies team leadership and emotional resilience, Davis co-taught a series of four workshops to head and assistant coaches at UVA with psychology professor Chris Hulleman in July 2020. The course – hosted by BattenX, the Batten School’s lifelong learning initiative – focused on motivating student-athletes, and proved so popular that he’ll be teaching another focused on emotional resilience in the near future.

Both coaches and athletes experience hardships differently than the average person, Davis noted. “They don’t face life-and-death adversity, but their highs and lows are higher and lower,” he explained. “Every year they go through either winning a conference championship or a devastating loss at the end of the season.

“For many of us, our ups and downs are much less intense and much more spread out.”

Regardless of their profession, some people respond to the lows in life more positively, he added. While it might seem natural to feel depleted after going through a difficult experience, some people come out feeling stronger. Within the context of athletics, Davis’s course explores how those people think.

Through lectures, discussion and evening take-home activities, coaches in the program learn to navigate challenges and use them as opportunities for growth. One particularly important concept the course covered last year, Davis said, was intrinsic motivation: valuing the work you do for its own sake. Participants also learned new techniques for communicating feedback and discussed what deep listening looks like on both the inside and the outside.

After sharing his experience at the state championship, Davis was impressed by how the coaches in his class were willing to be equally vulnerable – and to admit how much they had left to learn.

“I loved how open they were,” he said. “As a group of elite coaches, they have every reason to pose and act like they have it all together. And they do. These are very high-level people. But to hear them say, ‘That’s something I haven’t finished developing’ or ‘I need help in that area’ – it was really inspiring.”

Todd DeSorbo, UVA’s head swimming and diving coach who also will be an assistant coach for the U.S. swim team in the Olympics later this month, said that he enjoyed the opportunity to receive some outside guidance last summer.