In a virtual reality lab in the University of Virginia’s Clemons Library, with the aid of a headset and two hand controls, spectators walked through University Hall, the University’s now-closed athletic arena.

They could glide across the hardwood floor, then leap from there to the press box, to the scoreboard and to center court, flying through virtual space. They bounded from the court to the highest tiers of orange-and-blue seats, and even took a virtual stroll on the scalloped, cast-concrete roof.

It is in this virtual world that the iconic old building will survive, even after it is gone from the real one.

“U-Hall,” as it is commonly known, served for nearly five decades as the University’s sports arena and hosted many cultural events before closing to public use in 2015. With its role supplanted by John Paul Jones Arena, it is now slated for demolition in early summer.

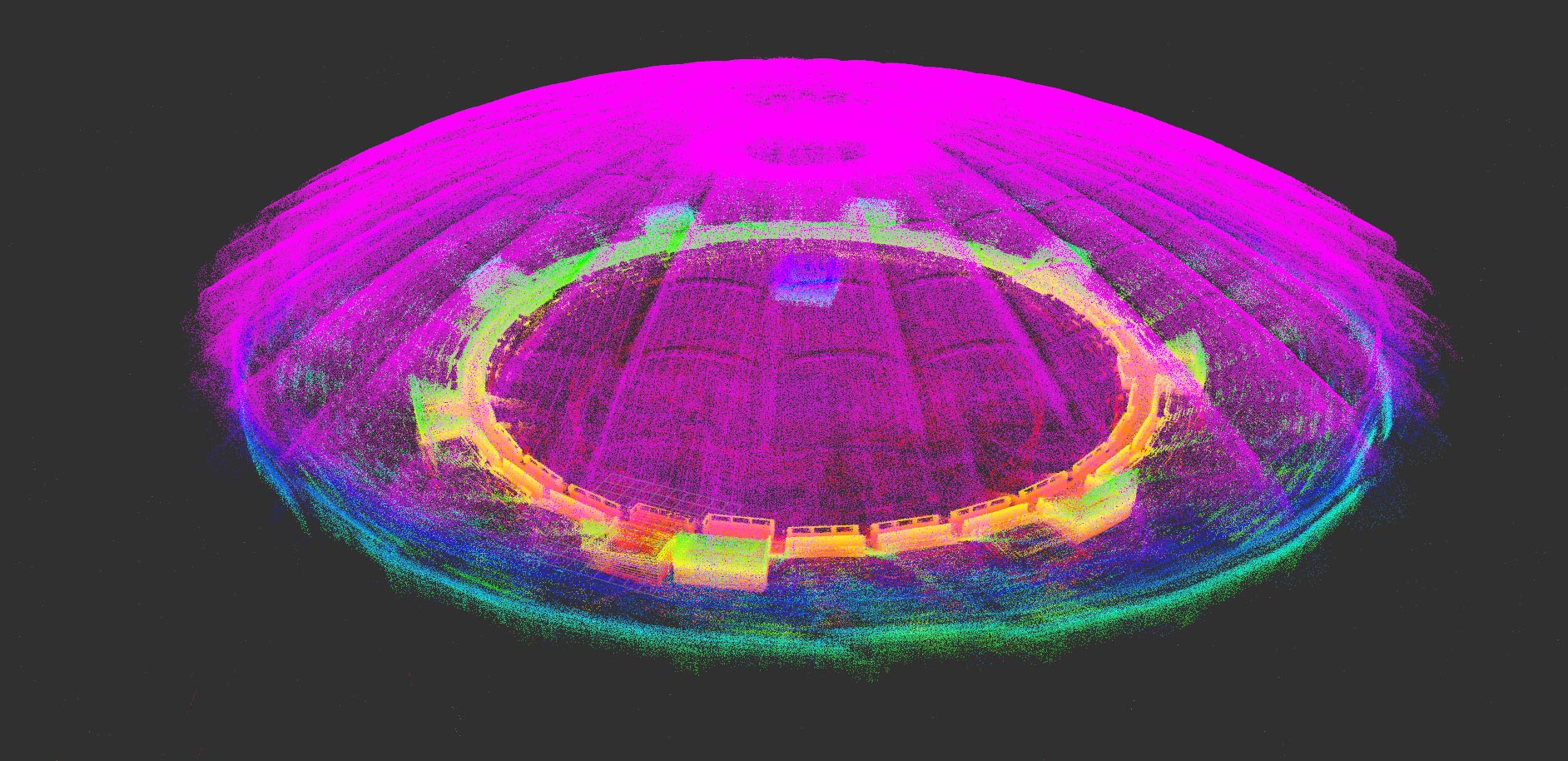

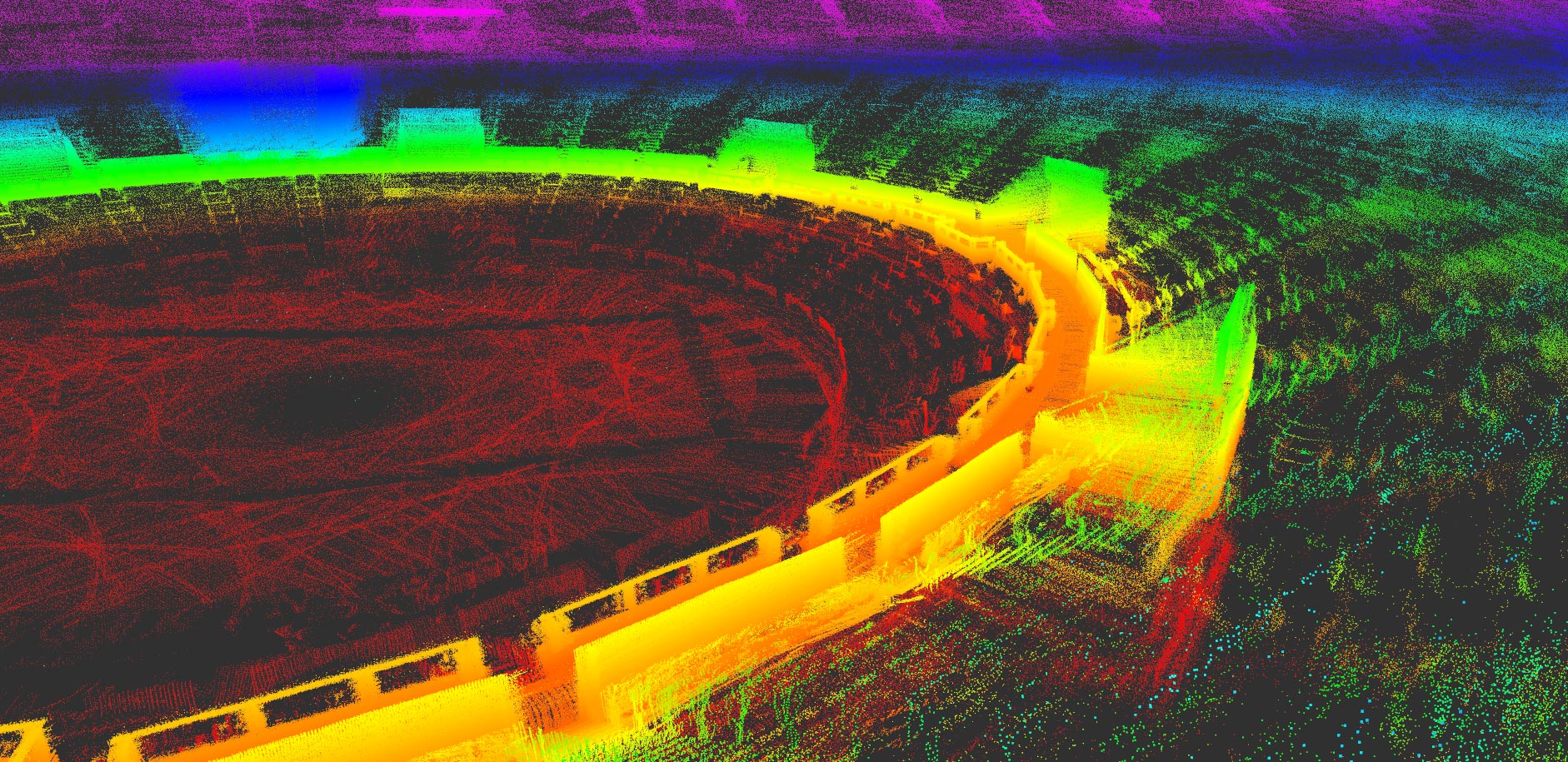

But before that happens, several UVA students, faculty and staff members are documenting the building with 3-D data-acquisition methods and still cameras. Once the data acquisition is complete, additional processing will create models that can be used for a variety of purposes, including virtual reality tours and 3-D reproductions.

“Once we’re done, you would be able to go over the data and rebuild it down to the millimeter,” said Will Rourk, a 3-D data and content specialist with the UVA Library’s Scholars’ Lab, who is collaborating on the digital preservation project with UVA’s Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities.

Rourk used lasers to scan the interior of University Hall, collecting surface data and measuring the space, using two scanners on tripods simultaneously reading different parts of the interior of the arena. Once he completed the arena, he scanned one of the locker rooms and the area that served as the “green room” for performance artists and bands.