March 31, 2008 — "I started out worrying that I would be called a professor of quirky subjects," confessed H.C. Erik Midelfort.

His research interests are, admittedly, unconventional: witch hunting in early modern Germany, exorcism, the Enlightenment and the history of madness. But after nearly four decades of teaching at the University of Virginia (he began here in 1970), the Julian Bishko Professor of History admits that it's not so bad being a professor of the unorthodox.

Midelfort doesn't teach early modern European history, so much as he enthralls those around him in his enthusiasm for it. U.Va's authority on the German Reformation (he holds a joint appointment in religious studies) said he stumbled into this topic and this time and place.

"I didn't know I was going to be a German historian when I went off to college," he said. "I thought I was going to be a doctor. My father was a doctor. His father was a doctor. My father's only brother was a doctor. I was supposed to be a doctor."

It was a foreign-language requirement, however, that landed him in Germany, where, in the summer after his junior year at Yale University, he became enamored of the land and its past. On a misty evening, he arrived in Tübingen, an old university town in the southwest corner of the country, and was instantly charmed. Later, when it came time to dig into the past for his doctoral dissertation on European witch trials during the 16th and 17th centuries (while also at Yale), he knew Tübingen was the place to start.

A penchant for witchcraft, madness and the Inquisition

Raised as a Lutheran in a Norwegian family in Eau Claire, Wisc., the young Midelfort also knew he had developed some useful insights into the thinking of Martin Luther, the leader of the Christian Reformation movement in Germany. So although he no longer identified with the Lutheran Church, he recognized the ideas and passions of Luther's Germany as a place from which he could begin his unique exploration of the past.

Midelfort said he chose the early modern period, mostly out of a desire to avoid delving into disasters.

"I absolutely loathed 20th-century German history," he said. "The history of the Nazis is so appalling, I thought 'I just can't do that. If I'm going to have a career in which I'm going to study interesting things, I don't want to study massacres. I don't want to study hateful, irrational pogroms and the Holocaust.' That was too gruesome."

Midelfort also had no interest in nationalism. So he went back to the early modern period, when what is now Germany consisted of many small fiefdoms under the Holy Roman Empire.

His research interests – witchcraft, madness and the Inquisition – are subjects as disturbing as the Holocaust. But perhaps, for him, their historical distance makes them seem somehow less gruesome.

"I thought, 'now there's a place you could find interesting,'" Midelfort said, "a confederation in which the nation-state is just not important and in which religious ideas were very important. I thought that was the most exciting thing in the world."

Midelfort spent his career exploring all manner of "interesting things," and has been recognized often for his outstanding scholarship.

His dissertation, "Witch Hunting in Southwestern Germany, 1562-1684: The Social and Intellectual Foundations," published in 1973, won the Gustav O. Arlt Award in the Humanities. His extensive research into madness in early modern Germany resulted in "Mad Princes in Renaissance Germany," published in 1994, and in "A History of Madness in Sixteenth-Century Germany," published in 1999. For both books, Midelfort won the Roland Bainton Prize for the best book of the year in History and Theology from the Sixteenth Century Society and Conference, the only scholar to win this award twice. He also received the Ralph Waldo Emerson Award from Phi Beta Kappa for the latter volume. Midelfort has been honored as a visiting scholar at several distinguished universities in the U.S and abroad, including Yale, Harvard, and both Wolfson and All Souls College at the University of Oxford.

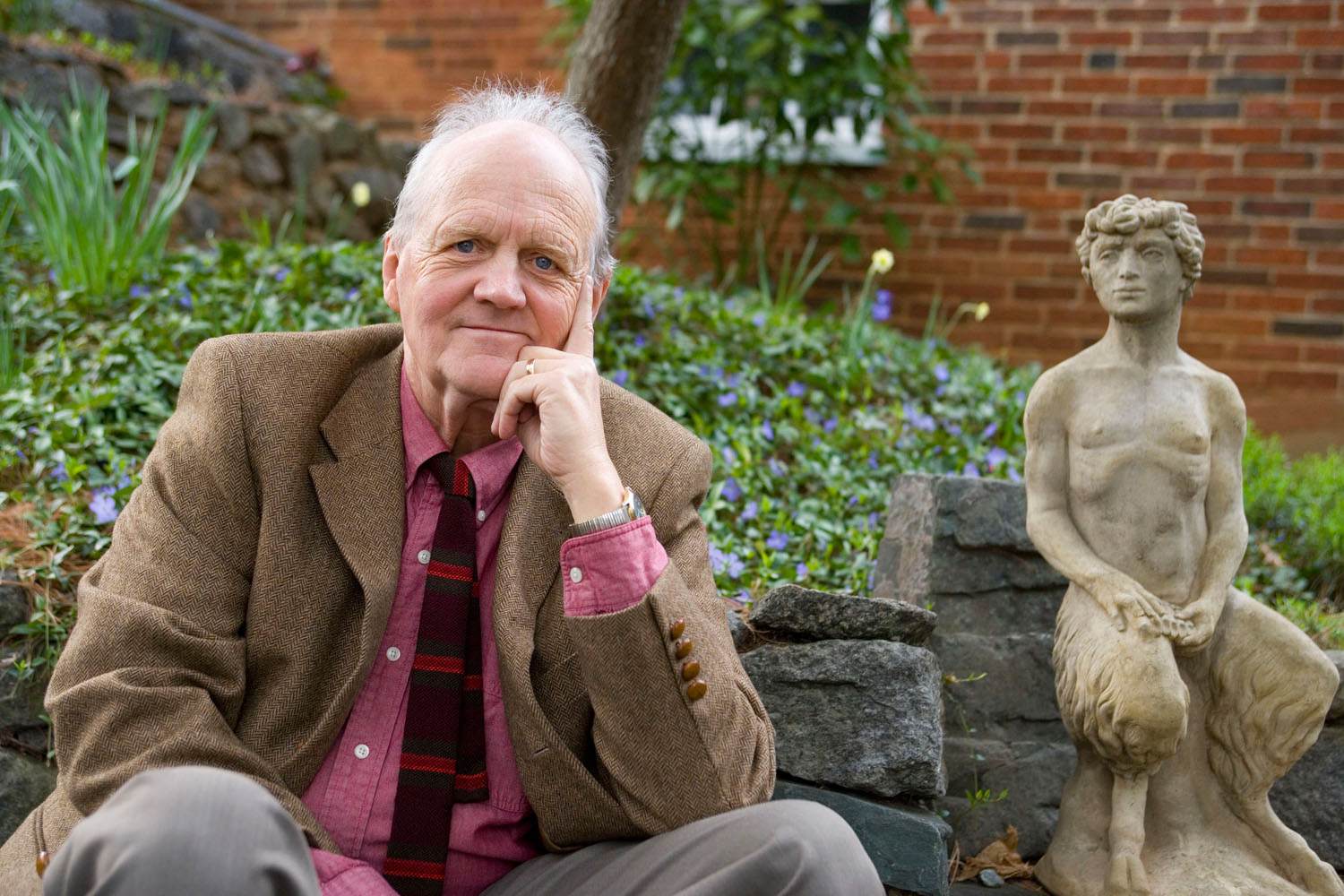

The man, like his work, has a reputation for being a bit offbeat.

"His sense of humor is really characteristic," said colleague Carl Trindle. Pointing at Midelfort's picture on the history department's Web page, Trindle suggested. "He's looking impish, and I think that's one word that would characterize him," Trindle said.

Trindle, a professor of chemistry, recalled that their friendship ignited one day in the cramped confines of the old Newcomb Hall bookstore as they each browsed for books outside their fields. Their camaraderie deepened over the years as fellows of Brown College.

Midelfort and Brown College

Next to his academic pursuits, Midelfort held most seriously his role as a founding member of the University's first residential college. He served as its principal from 1996 to 2001, and though he no longer lives, eats and works among the 500 students living on Monroe Hill, he continues to maintain a strong presence.

Midelfort admits that he loves to talk — perhaps a little too much — and is a notorious storyteller.

"You really have to discipline yourself if you ask him a question," Trindle said, "because he will answer it — to all sorts of diverting¬ and interesting lengths."

In the autumn of the year, when the students of Brown College are making mischief with their annual Halloween haunted house, the witchcraft scholar is often called upon to employ this gift of gab as he advises students on how they can tell if their roommate is a practitioner of the dark arts.

"There are various well-established ways to know," Trindle deadpans in an imitation of his colleague.

Midelfort might inquire of the student: "Have you gotten an unfortunate grade lately? Have you had a run of bad luck? It's one of the clear clues." Then he'd quote from the famous medieval treatise on witches, "Malleus Maleficarum," in support of the available evidence.

An intensely curious advisor

For Margaret Lewis, this combination of humor and intense curiosity is what makes Midelfort such a good academic advisor. "He seems to know everything," the second-year graduate student said. "He's very good at asking tough questions. And he's fascinated by whatever you're researching, even if it's not history or is something of personal interest."

Perhaps this is because Midelfort enjoys and is fascinated by everything he does. Teaching a first-year seminar on "The Great Heresies," for example, is his idea of fun. It's a course that has brand-new college students read about Socrates, Jesus, Galileo and Darwin, and asks the question: What was it that got these "heretics" into trouble?

"That's fun!" Midelfort said. "Let's have a little moral earnestness here in the first year. Let's talk about what sort of life one should live. That's not such a bad question to ask when you're a first-year student."

He also enjoys sailing, although having grown up in Wisconsin, a state pockmarked with glacial lakes, he doesn't understand a state like Virginia that only has rivers. He and his wife, Anne McKeithan, read aloud to each other almost every evening. Over the years, they have made their way through nearly 100 volumes — everything from Trollope to Garrison Keillor.

"Okay, let's just face it," Midelfort said. "I have a thing for quirky or offbeat or weird topics. But it's because of the amazing light they shed on topics that are ordinarily considered in a conventional way."

His research interests are, admittedly, unconventional: witch hunting in early modern Germany, exorcism, the Enlightenment and the history of madness. But after nearly four decades of teaching at the University of Virginia (he began here in 1970), the Julian Bishko Professor of History admits that it's not so bad being a professor of the unorthodox.

Midelfort doesn't teach early modern European history, so much as he enthralls those around him in his enthusiasm for it. U.Va's authority on the German Reformation (he holds a joint appointment in religious studies) said he stumbled into this topic and this time and place.

"I didn't know I was going to be a German historian when I went off to college," he said. "I thought I was going to be a doctor. My father was a doctor. His father was a doctor. My father's only brother was a doctor. I was supposed to be a doctor."

It was a foreign-language requirement, however, that landed him in Germany, where, in the summer after his junior year at Yale University, he became enamored of the land and its past. On a misty evening, he arrived in Tübingen, an old university town in the southwest corner of the country, and was instantly charmed. Later, when it came time to dig into the past for his doctoral dissertation on European witch trials during the 16th and 17th centuries (while also at Yale), he knew Tübingen was the place to start.

A penchant for witchcraft, madness and the Inquisition

Raised as a Lutheran in a Norwegian family in Eau Claire, Wisc., the young Midelfort also knew he had developed some useful insights into the thinking of Martin Luther, the leader of the Christian Reformation movement in Germany. So although he no longer identified with the Lutheran Church, he recognized the ideas and passions of Luther's Germany as a place from which he could begin his unique exploration of the past.

Midelfort said he chose the early modern period, mostly out of a desire to avoid delving into disasters.

"I absolutely loathed 20th-century German history," he said. "The history of the Nazis is so appalling, I thought 'I just can't do that. If I'm going to have a career in which I'm going to study interesting things, I don't want to study massacres. I don't want to study hateful, irrational pogroms and the Holocaust.' That was too gruesome."

Midelfort also had no interest in nationalism. So he went back to the early modern period, when what is now Germany consisted of many small fiefdoms under the Holy Roman Empire.

His research interests – witchcraft, madness and the Inquisition – are subjects as disturbing as the Holocaust. But perhaps, for him, their historical distance makes them seem somehow less gruesome.

"I thought, 'now there's a place you could find interesting,'" Midelfort said, "a confederation in which the nation-state is just not important and in which religious ideas were very important. I thought that was the most exciting thing in the world."

Midelfort spent his career exploring all manner of "interesting things," and has been recognized often for his outstanding scholarship.

His dissertation, "Witch Hunting in Southwestern Germany, 1562-1684: The Social and Intellectual Foundations," published in 1973, won the Gustav O. Arlt Award in the Humanities. His extensive research into madness in early modern Germany resulted in "Mad Princes in Renaissance Germany," published in 1994, and in "A History of Madness in Sixteenth-Century Germany," published in 1999. For both books, Midelfort won the Roland Bainton Prize for the best book of the year in History and Theology from the Sixteenth Century Society and Conference, the only scholar to win this award twice. He also received the Ralph Waldo Emerson Award from Phi Beta Kappa for the latter volume. Midelfort has been honored as a visiting scholar at several distinguished universities in the U.S and abroad, including Yale, Harvard, and both Wolfson and All Souls College at the University of Oxford.

The man, like his work, has a reputation for being a bit offbeat.

"His sense of humor is really characteristic," said colleague Carl Trindle. Pointing at Midelfort's picture on the history department's Web page, Trindle suggested. "He's looking impish, and I think that's one word that would characterize him," Trindle said.

Trindle, a professor of chemistry, recalled that their friendship ignited one day in the cramped confines of the old Newcomb Hall bookstore as they each browsed for books outside their fields. Their camaraderie deepened over the years as fellows of Brown College.

Midelfort and Brown College

Next to his academic pursuits, Midelfort held most seriously his role as a founding member of the University's first residential college. He served as its principal from 1996 to 2001, and though he no longer lives, eats and works among the 500 students living on Monroe Hill, he continues to maintain a strong presence.

Midelfort admits that he loves to talk — perhaps a little too much — and is a notorious storyteller.

"You really have to discipline yourself if you ask him a question," Trindle said, "because he will answer it — to all sorts of diverting¬ and interesting lengths."

In the autumn of the year, when the students of Brown College are making mischief with their annual Halloween haunted house, the witchcraft scholar is often called upon to employ this gift of gab as he advises students on how they can tell if their roommate is a practitioner of the dark arts.

"There are various well-established ways to know," Trindle deadpans in an imitation of his colleague.

Midelfort might inquire of the student: "Have you gotten an unfortunate grade lately? Have you had a run of bad luck? It's one of the clear clues." Then he'd quote from the famous medieval treatise on witches, "Malleus Maleficarum," in support of the available evidence.

An intensely curious advisor

For Margaret Lewis, this combination of humor and intense curiosity is what makes Midelfort such a good academic advisor. "He seems to know everything," the second-year graduate student said. "He's very good at asking tough questions. And he's fascinated by whatever you're researching, even if it's not history or is something of personal interest."

Perhaps this is because Midelfort enjoys and is fascinated by everything he does. Teaching a first-year seminar on "The Great Heresies," for example, is his idea of fun. It's a course that has brand-new college students read about Socrates, Jesus, Galileo and Darwin, and asks the question: What was it that got these "heretics" into trouble?

"That's fun!" Midelfort said. "Let's have a little moral earnestness here in the first year. Let's talk about what sort of life one should live. That's not such a bad question to ask when you're a first-year student."

He also enjoys sailing, although having grown up in Wisconsin, a state pockmarked with glacial lakes, he doesn't understand a state like Virginia that only has rivers. He and his wife, Anne McKeithan, read aloud to each other almost every evening. Over the years, they have made their way through nearly 100 volumes — everything from Trollope to Garrison Keillor.

"Okay, let's just face it," Midelfort said. "I have a thing for quirky or offbeat or weird topics. But it's because of the amazing light they shed on topics that are ordinarily considered in a conventional way."

— By Linda Kobert

Media Contact

Article Information

March 31, 2008

/content/erik-midelfort-serious-interest-offbeat-history