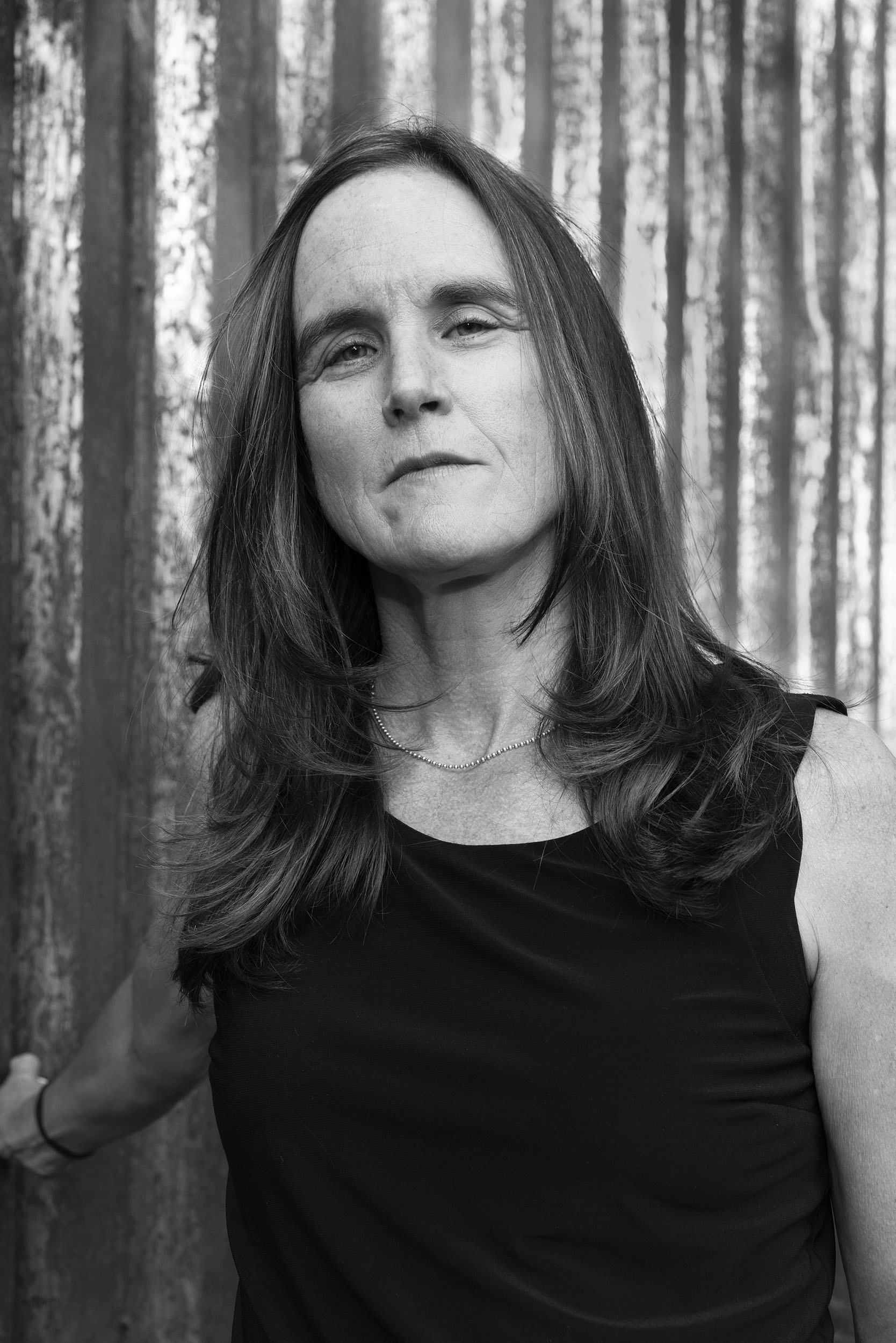

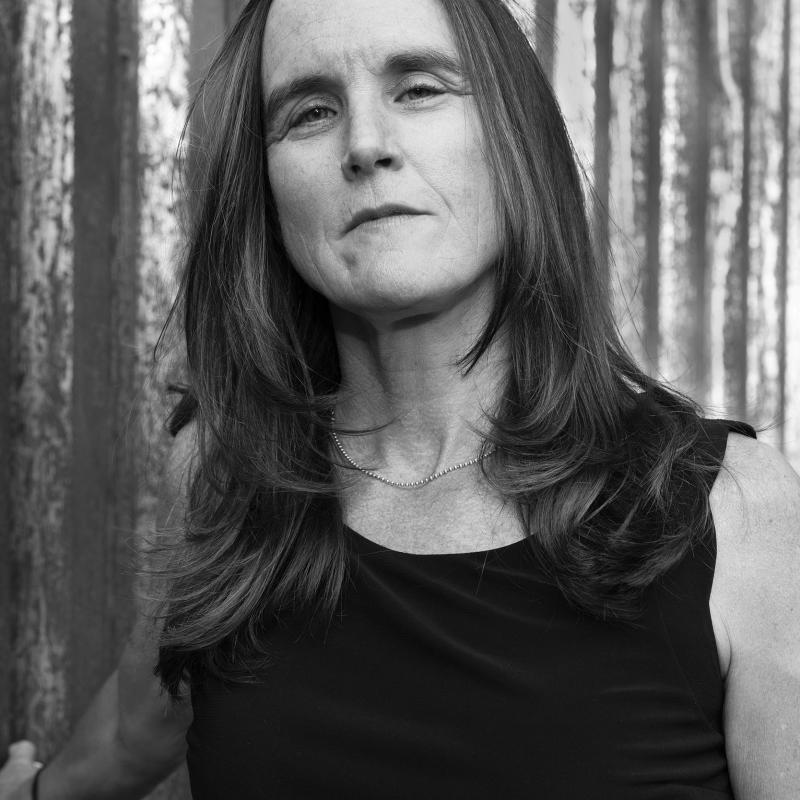

“I kept thinking somebody else would do it, would interview all of these people, because there is a really important story here to tell,” she said. “But Vic’s death made me realize that people weren’t going to be around to interview and I needed to get started.”

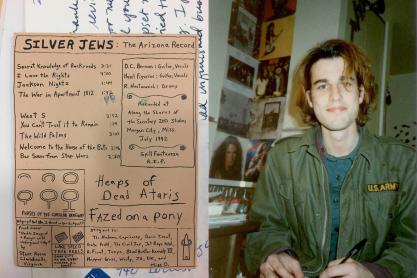

Hale began by interviewing people she knew and then reaching out to their contacts. She also dug into back issues of local publications for concert schedules and music reviews, as well as privately held materials including recordings, photographs, press clippings and band flyers. At times, she purchased important materials on websites such as Ebay. The research took years because there was no official archive, although the hometown University of Georgia is now actively collecting these kinds of materials.

“People’s memories are right about what it felt like, and what the tone was, and what the takeaway was for their experience, and you get some great stories and some great insights that way,” Hale said, “but often our memories are wrong about particularities. Like the date that you thought you saw this band at that club, and it was actually another, or who opened for that band on that night actually wasn’t the one that you remembered. So much time had passed that I had an ability to come back to that material with a more critical eye – or at least with the sense that I needed to check what I remembered with other sources.”

But Hale’s personal involvement gave her entrée into other aspects of the story.

“Because I had been there, I had a sense of what the important stories were, such as figures that the larger world never knew about,” she said. “They never got ‘famous’ in some larger way, but they were key figures in terms of the myth or the reality of the place. That gave me a starting point that I think would be hard to have if you did not have some direct experience.

“Having an understanding of what is going on in the larger world and how the local and the particular might connect to larger themes that are important – being a historian is helpful there,” she said. “‘Cool Town’ is an attempt to think seriously about what alternative cultures can do, in a way that is actually interesting for anyone who loves indie music to read.”

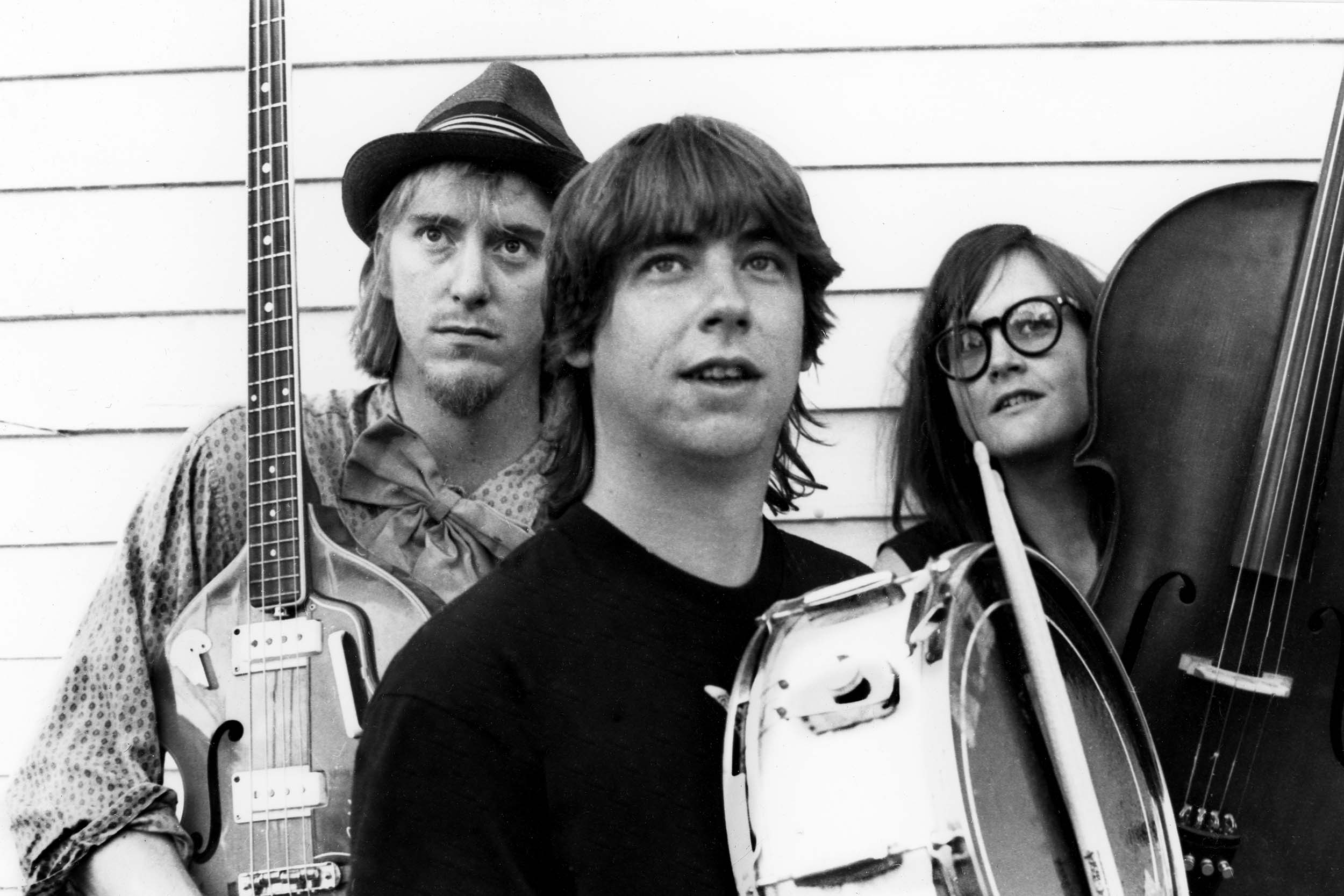

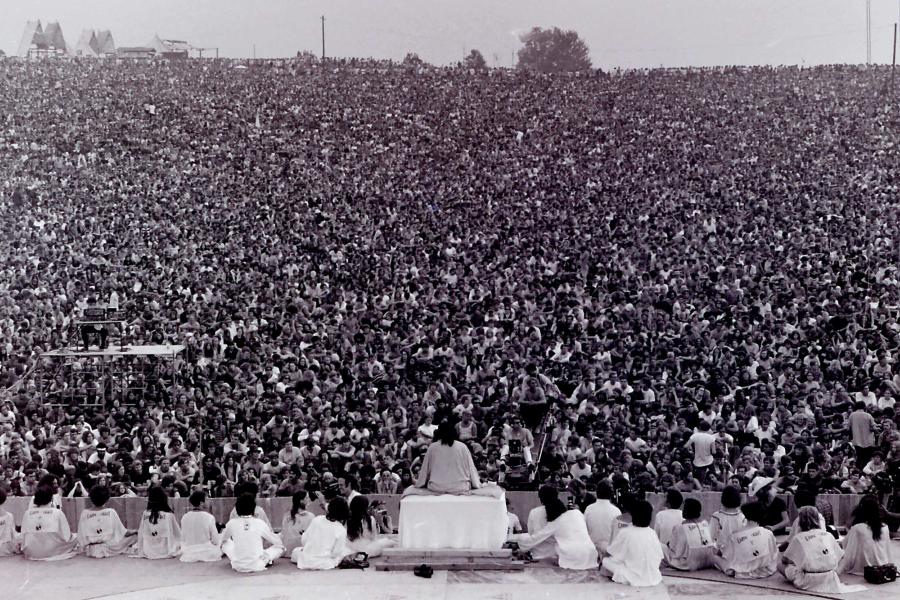

The Athens scene was a combination of ingredients – key people in the right places at the right times who came out of a university town, where young people could live cheaply and had access to the cultural resources available for free in those pre-internet days at a large, public university, including music libraries, film libraries and old magazines.

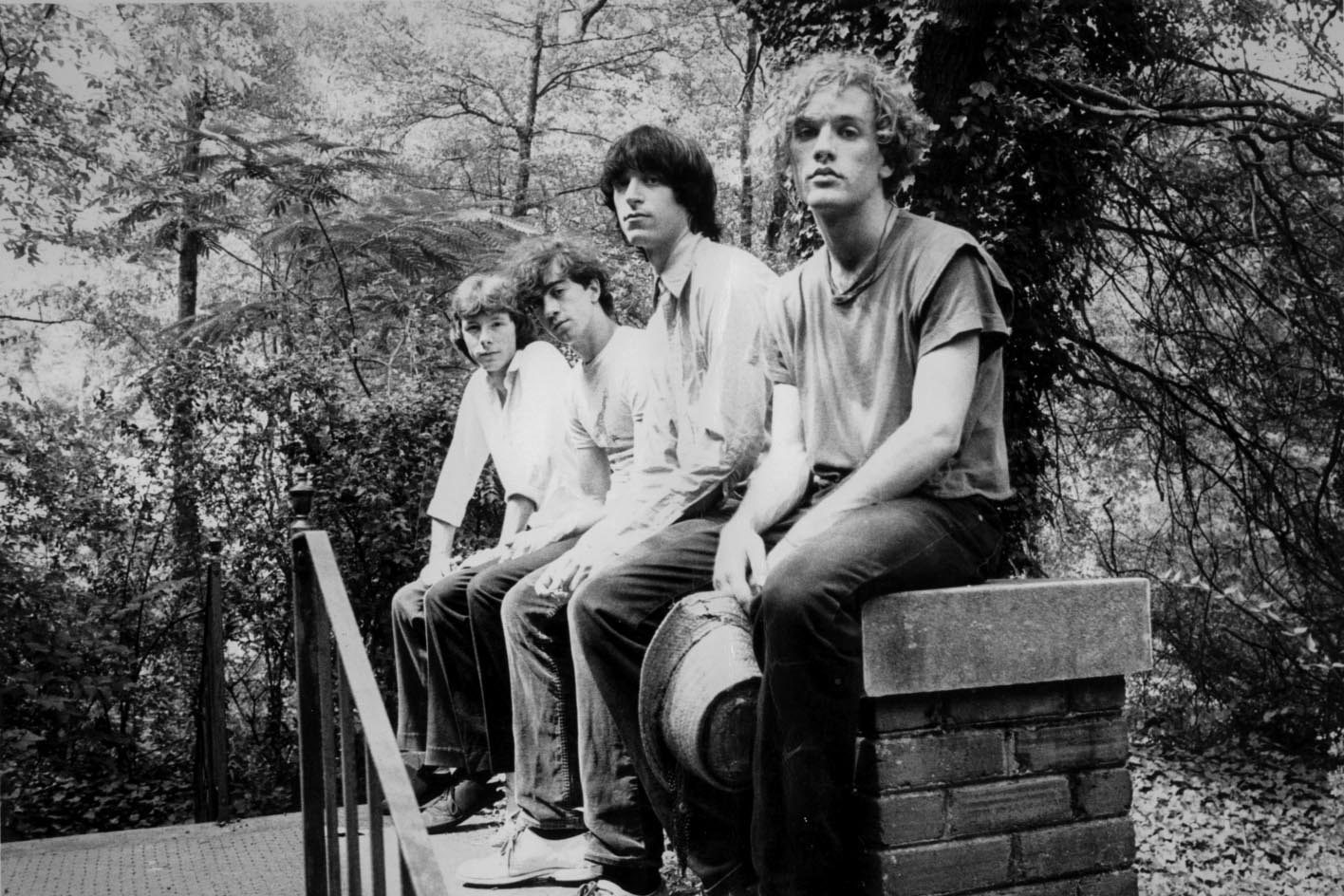

“A few key individuals came along and decided to stay in town and not move to New York, and that made Athens different,” Hale said. “Without having the amazing folks in The B-52s, you don’t have Athens; without Ricky Wilson and Keith Strickland [two founders of The B-52s] there is no Athens scene. But they can’t really make it there as a band in the late 1970s because there is a not an infrastructure yet.

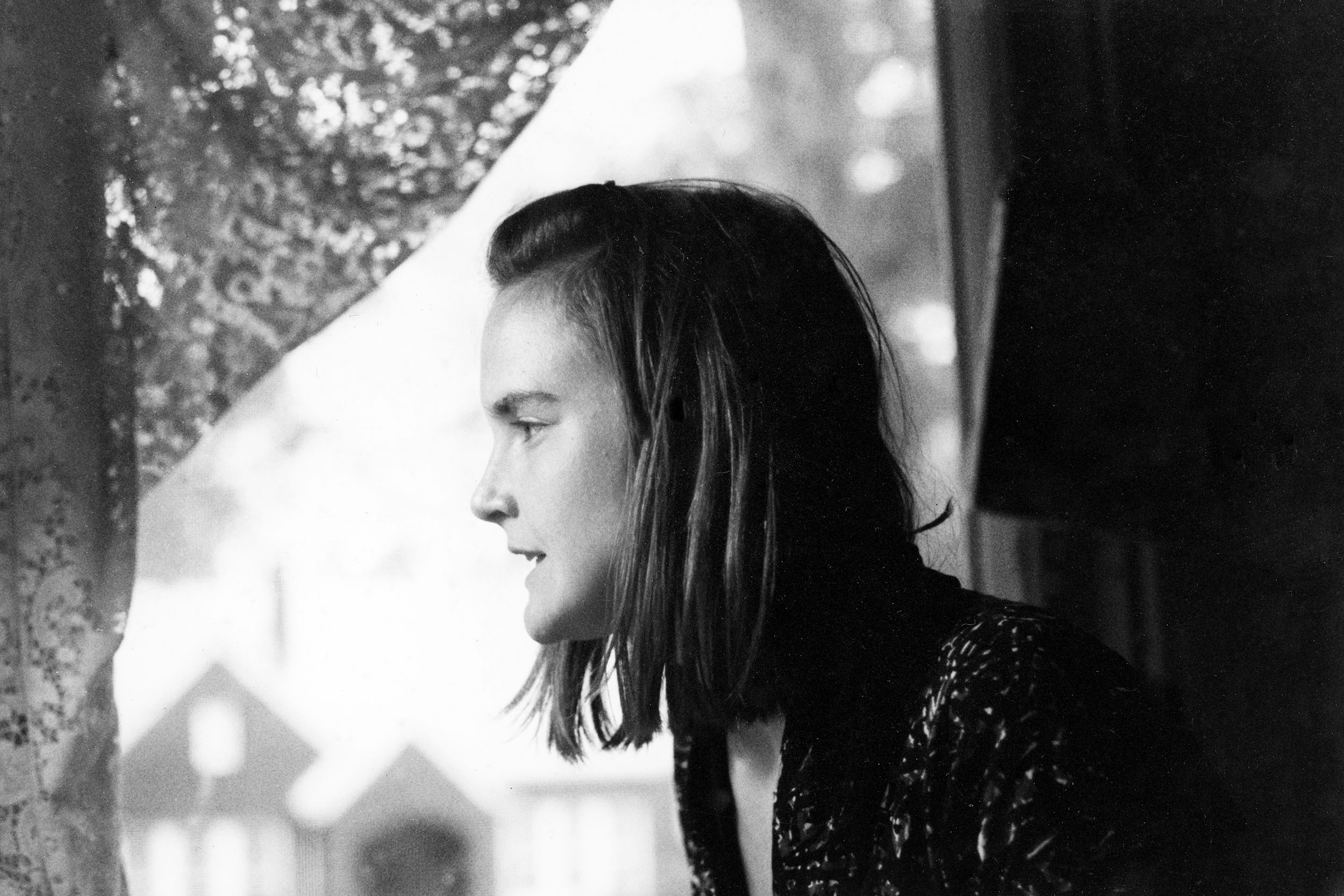

“At the same time, people in town like Jerry Ayers, a close friend Wilson and Strickland met when they were still in high school, was hugely influential on them. He had been a part of Andy Warhol’s Factory, and after living in New York City for a while in the 1970s, he came back to live in Athens until he died a few years ago. Jerry, later Jeremy, Ayers mentored wave after wave of people who participated in the Athens scene over the decades.”

And while The B-52s eventually chose to leave Athens to pursue their career, other bands that came after them, like Pylon, made the choice to stay and remain rooted in the local creative community that they had helped create.