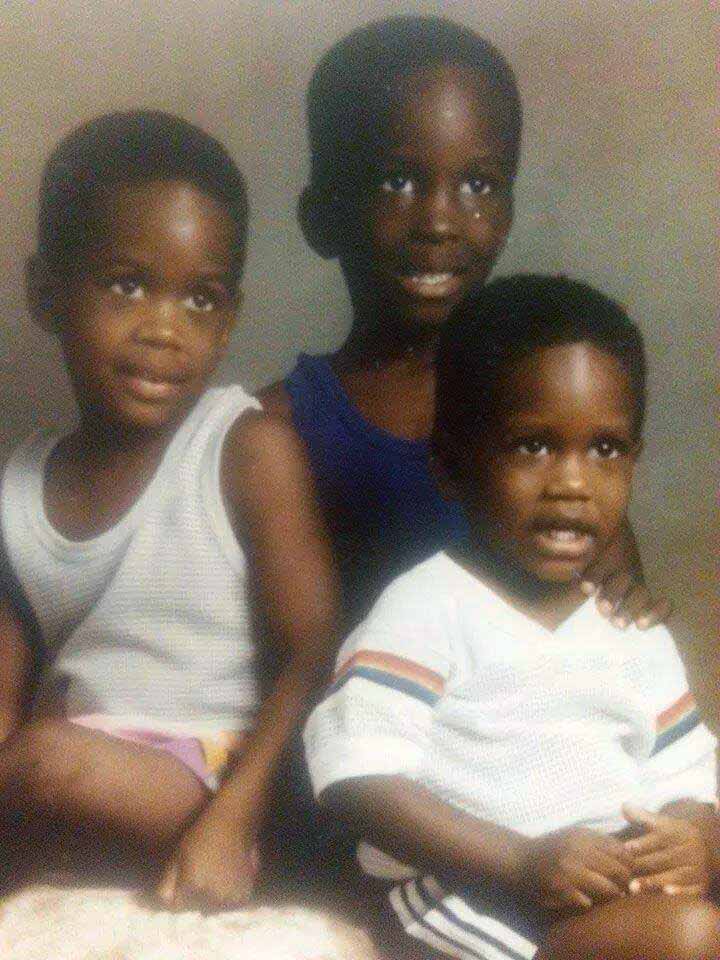

After the divorce, Williams, just like his brothers, began misbehaving in school. But then one day Williams overheard a conversation his mother was having with a friend. It changed everything.

Williams’ mother was talking to one of her friends about how proud she was of her son. “It was about something really little I had done in school,” said Williams, then an elementary-schooler. “I remember thinking, ‘She’s proud of that? Well, that’s nothing. I can do better than that.’

“I could have cared less about school, but it became like, ‘I’ll do this for her.’ Our relationship was that important. And then when I got to high school, it became more of, ‘Well I can do this for myself now.’”

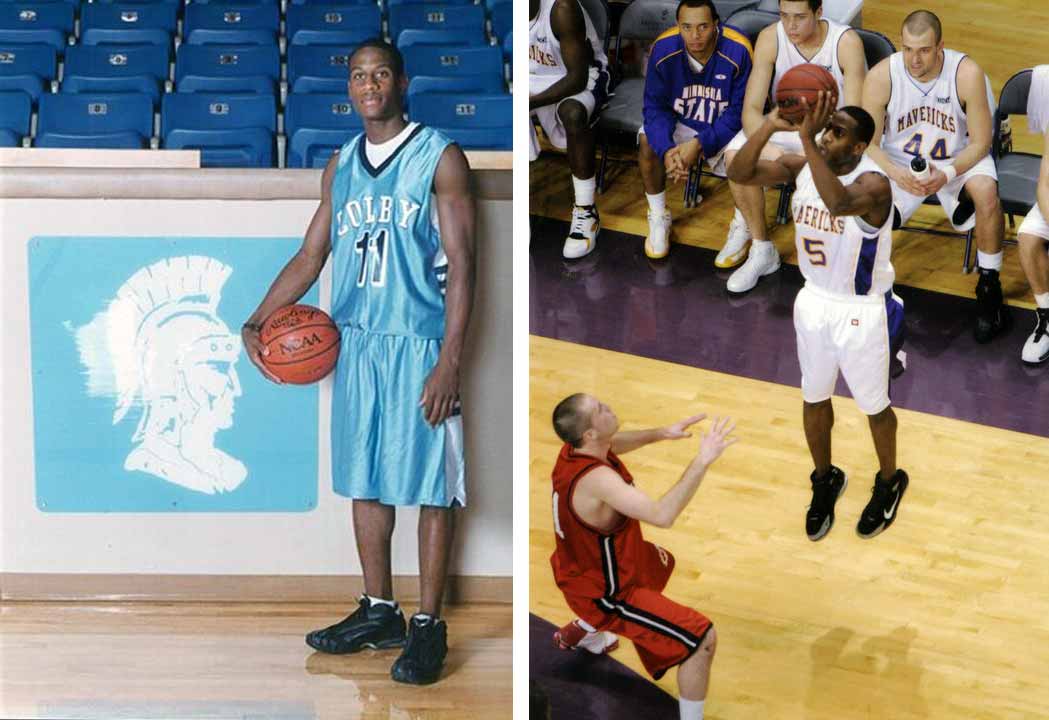

He excelled in the classroom and on the basketball court before going on to Colby Community College in Colby, Kansas. After two years there, he received scholarship offers from lower-level Division I schools.

Ultimately, wanting to be part of a winning program, Williams accepted an offer from Division II powerhouse Minnesota State, where he earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees.

Following his playing career, Williams was encouraged by Diane Coursol a grad school faculty member and mentor, to go for his Ph.D.

“She really pushed the idea from a generational, breaking-poverty cycle [standpoint],” Williams said. “She said, ‘Think about what you could do for your brothers and nieces and nephews.’

“And I saw that it could give me a platform to do meaningful research to help kids and address social justice issues.”

Williams, a faculty affiliate with Youth-Nex: The UVA Center to Promote Effective Youth Development, and with the Center for Race and Public Education in the South, is doing just that, according to Curry School associate professor Nancy Deutsch.

“His work is truly inspired and inspiring,” she said. “He is deeply committed to making a real change in the lives of young people, particularly youth of color and youth who are often marginalized and underserved by our educational systems.

“He has generously given his time, energy and expertise to the local schools, providing workshops and talks on racial equity and related topics for teachers, parents and administrators. He is someone who practices what he preaches – not only working to train the next generation of scholars, but giving of his time to also work with local school systems to help provide support for current teachers and parents.”

A number of teachers who have attended Williams’ workshops and presentations have gone out of their way to tell Deutsch how impressed they were with his ability to connect with audiences about topics that can be difficult to talk about.

“He is able to speak the truth, but deliver it in a manner that allows a diverse audience to hear it,” Deutsch said. “That is a rare talent, and one that he is putting to good use in his work both in UVA’s classrooms and in our local community.”

“I don’t want them to think that basketball is their only way out. It’s about what extracurricular activities can do for you.”

- Joseph Williams

Williams, 37, has remained close with his brothers. His mother, remarried and living in Texas, is also a very big part of his life. “She’s always been strong,” Williams said. “We call her the pillar in our family.”

Williams’ father died in a car accident about four years ago. Several years before, he had achieved sobriety. Williams talked with him regularly, having long come to terms with his actions.

“I’ve learned that while we must hold ourselves accountable for the choices that we make, our choices are shaped and at times constrained by our environment. I often think about what it must have been like for my father growing up in the ’60s, and ’70s with few employment opportunities, the hyper-criminalization of black men, among other things – I can see how why he made some of the choices he made.”

One of the biggest takeaways in Williams’ research pertaining to how children overcome obstacles has been the importance of relationships. Williams said successful students, no matter how crazy their life experiences have been, are able to establish meaningful ones both inside and outside of schools, with peers and adults alike.

“It’s like a reciprocal thing – ‘I help you with this – will you help me with this?’” said Williams, referring to peer relationships. “Like we share resources because we don’t have a lot.”

For Williams, that was yet another benefit of playing basketball.

Looking back on his childhood, Williams knows how fortunate he was to have had the sport.

When Williams isn’t buried in his work, he still loves to play; he’s always on the lookout for good pick-up games in and around Charlottesville.

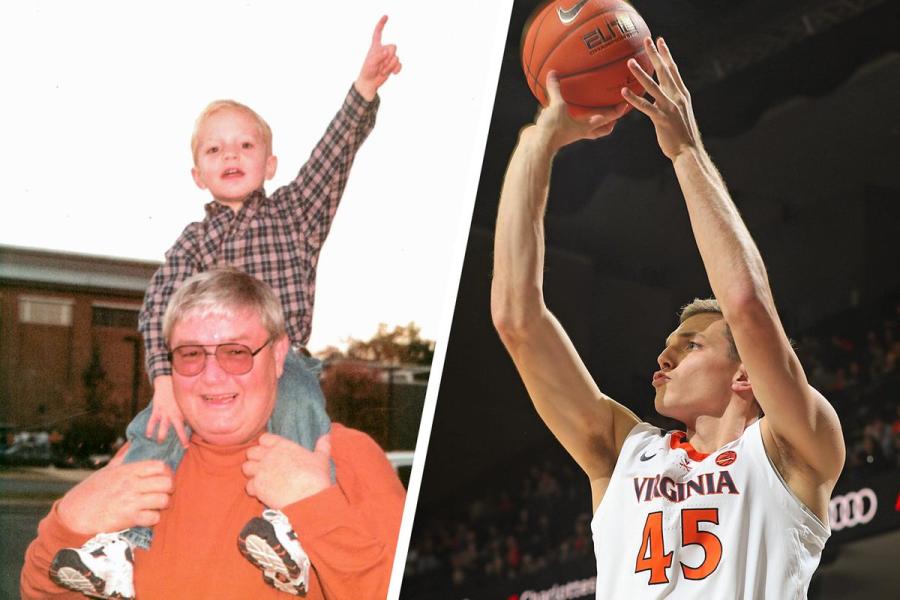

His love for basketball is obvious. When he talks about the finer points of the sport – such as court spacing and moving without the ball – he becomes animated, especially as it pertains to teaching those points to his 8-year-old son.

But when Williams speaks to children in the community, he’s sometimes hesitant to tell them about the role basketball played in his life.

“I don’t want them to think that basketball is their only way out,” he said. “It’s about what extracurricular activities can do for you. It’s not really about basketball. It’s about what I developed from it – like character traits, discipline, leadership skills, etc. There were just all these things I learned from this game.

“So it’s about, ‘What are you into, what are you passionate about and how can you leverage it?’ Even if you don’t play sports, anything that actually provides structure can be used as a learning tool.”

Williams knows that sharing the details of his own childhood, no matter how painful some of them can be, helps change lives.

“I’ve never been ashamed of my upbringing,” he said, “but am very humbled by it.”