Editor's note: This article was originally published in April 2021.

Faculty Spotlight: Professor Studies Sounds of Justice

What is the power of one human voice, in speech or song?

The sound of a human voice can bring us together or can be ignored.

When Nomi Dave got her dream job with the United Nations, little did she know it would lead to a path very different than she had imagined, one that would range from studying music in authoritarian Guinea, to documenting women speaking out for gender justice, to teaching at the University of Virginia.

Dave, an associate professor of music who just gained tenure, recently won a book prize for best first monograph, “The Revolution’s Echoes: Music, Politics, and Pleasure in Guinea” from the Society for Ethnomusicology.

With ancestral roots in Africa, Dave had known since she was a teenager that she wanted to spend time somewhere on the continent. Her route was circuitous, however.

She and her brother were born in London, where their parents had studied. The family also spent time in Kenya when she was little and moved to the U.S. when she was 11. (Although her family originated in India, they were part of a long-standing Indian diasporic community in East Africa, including Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda.)

“Those experiences lit a fire in my imagination,” she said.

Dave earned her B.A. at the University of Florida, majoring in French and politics with a minor in African studies. She knew she was interested in international policy, and law school would give her the tools to work in international human rights. She then moved to New York City and worked at the United Nations headquarters – at the time, a dream come true, she said – for two years before applying for a post with the U.N. Refugee Agency.

She spent three years in Conakry, the capital of Guinea, from 2002 to ’05, working with refugees, including those in detention and in prison, and then focusing on women and children caught in armed conflicts. Hundreds of thousands of people had fled to Guinea from civil wars in nearby Sierra Leone, Liberia and Ivory Coast. Dave worked on family reunification cases involving unaccompanied minors, trying to trace and connect them to their families. Cases of sexual violence were not uncommon.

“I felt like I was putting out fires without time to understand what was happening below the surface,” she said.

“It was extraordinary, but I became disillusioned about the huge bureaucracy.” Dave said working in Guinea itself was tangential.

“I felt frustrated I didn’t know about this place where I was living,” she said. She was still interested in law and politics, but also felt drawn to music – an interest that tugged at the edges of her life. She loved Guinean music. She found that people were often hesitant to talk with a foreigner about politics, but opened up talking about music, and she realized they were linked.

After taking a break and thinking about what to do next, she decided to go back to school.

From Lawyer to Sound Researcher

Dave went to Oxford University, completing her Ph.D. in 2012 in anthropology and music, returning to Guinea for field work. She now conducts research and teaches about the role music and sound play in culture and politics, as well as uses of the human voice, literally and figuratively.

Since Guinea gained its independence from France in 1958, several authoritarian rulers led the government and have used music to reflect pride and look back on the country’s history with nostalgia.

Back in Guinea as a doctoral student, she dug into the authoritarian undercurrents and the dynamics of music and politics, looking at what it all might mean for ordinary people.

Alya Camara, a bolon player, shown in 2019 in Conakry, Guinea, in front of a mural of the former president. (Photo by Nomi Dave)

The tradition of praise-singing – paying musical homage to nobles and rulers – evolved to promoting the postcolonial state, with musicians and audiences actively participating.

Political theory, Dave pointed out, has long acknowledged that emotion plays a role in politics – leaders can use their charisma to invoke fear as well as pleasure.

“In fact, authoritarianism works not just through fear or false consciousness, but also through creating a sense of belonging and collectivity for people,” she said.

In her own experiences while doing research, she could feel the palpable sense of public pleasure at concerts, she said, even when the musicians were singing about an authoritarian leader that people disliked. 2010 brought democratic elections, but the shift to a post-authoritarian state has been destabilizing and slow, she said.

“My main argument,” Dave wrote in email about the prize-winning book that resulted from her research, “is that people always love the idea of protest music – especially in Africa, foreigners are always looking for stories of protest musicians – but in fact the vast majority of musicians intentionally don’t engage in protest or politics. That’s true in Guinea, in the U.S., in most places around the world.”

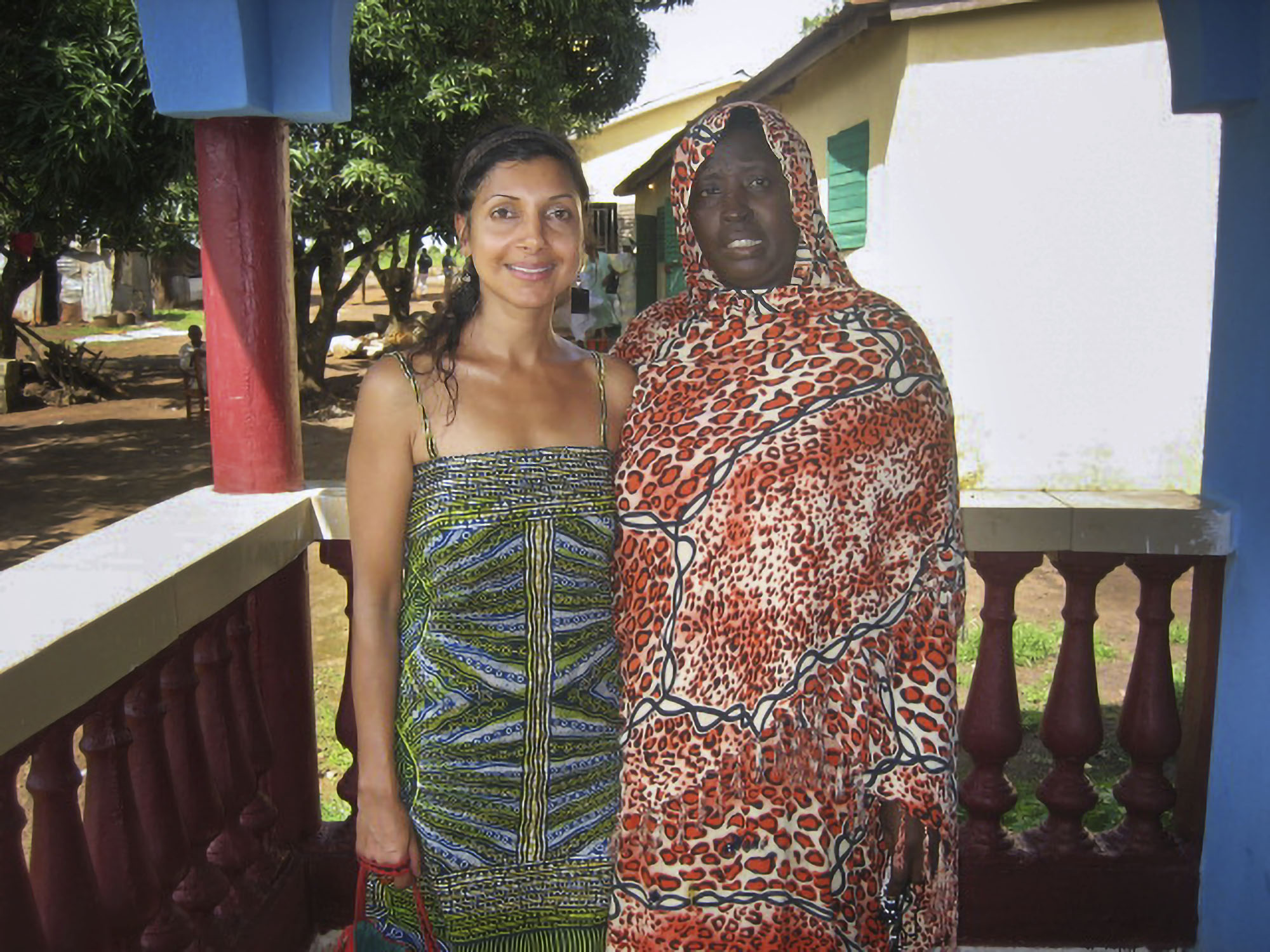

Dave, with her former vocal teacher, Diaryatou Kouyaté, in Guinea in 2009. (Photo by Cheick Kouyaté)

Today as Guinea makes an uneasy transition to democratic rule, such spectacles of public pleasure are becoming increasingly unstable, as new forms of protest and political voice complicate older aesthetic practices, she said.

“There’s been an increasing amount of open, vocal dissent and protest in the country, in which people – journalists, students, street protesters – call out politicians directly,” Dave said. “Musicians are trying to navigate this change – from the old pleasures of musical and poetic shout-outs to a new political culture of calling out. What’s important to note here is that for the most part, musicians aren’t leading the vanguard to protest; instead, they’re really torn between old and new ways.”

Sounds of New Research and Teaching With Community Engagement

Dave’s scholarship has also shifted. She has returned to her earlier work as a lawyer to see how people try to seek justice – with their voices, in the streets and on the radio.

With her background, Dave is bringing together law, anthropology and sound studies, a subdiscipline that looks at what sound means to us.

Beyond metaphor, the way we hear different sounds is filtered through ideas we already have, Dave said. It is still all too common that women’s voices are criticized in stereotypical ways – for being whiny or shrill, for example, but they continue to speak out anyway.

Women activists in Guinea have been protesting against gender-based violence on the radio and in the streets. Before COVID, Dave had planned a radio series with women in Conakry to familiarize listeners with the women’s voices, but that was cut short by the pandemic and not being able to return and interview women there.

With Bremen Donovan, a UVA doctoral student in anthropology, Dave is making a short documentary film about a defamation lawsuit against a Guinean journalist and activist, Moussa Yéro Bah, who covered sexual violence cases – a legal tactic that has been used to silence journalists, she said.

Dave and Donovan presented an early rough cut of the film at the RAI Film Festival, held virtually March 19 to 28. Sponsored by the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, the biennial conference is “the leading forum for exploring the multiple relationships between documentary filmmaking, anthropology, visual culture and the advocacy of cultural diversity and intercultural dialogue through film,” according to its website.

Dave said they’re also organizing a roundtable at UVA, to be held in early May, with “some amazing participants here”: media studies professor Meredith Clark, law professor Anne Coughlin and filmmaker Kevin Everson.

Donovan, who lived in Sierra Leone, has known Dave for several years and said in email, “This film project has been a wonderful experience of collaboration around our mutual interests in law, justice and creative approaches to research, that live beyond the university. Working with collaborators [in Guinea] for this project has been a highlight of this year.”

In this still from the film Dave is making, Guinean activists hold a press conference after a guilty verdict in a defamation lawsuit. (Photo by Nomi Dave)

Dave has woven some of this research into her teaching as part of the College of Arts & Sciences’ Civic & Community Engagement program. She described her course, “Musical Ethnography,” as “a yearlong course that’s half classroom-based learning on methods and ethics in ethnographic research, and half creative projects and collaborations with local musicians and artists in Charlottesville.”

She said the students have been amazing, reimagining and turning their projects into virtual concerts for an open mic series; a video-recording of a song by a local group of eco-activists, The Green Grannies, produced for Earth Day; and a virtual benefit concert for the Shelter for Help in Emergency, featuring many of their artist-partners.

This year, Dave’s third and last year of teaching this course for a while, one of the students, Noelle Buice, came up with the idea of making an arts-based time capsule focusing on the COVID pandemic.

“Students are making a short film, a podcast, a photo essay, and a text collage about artists’ thoughts and memories for this past year,” Dave said, adding that the class is partnering with the local organization, the Bridge Progressive Arts Initiative, and WTJU, to host the virtual time capsule on the Bridge’s website. “We’re also creating a physical time capsule with objects collected from artists and community members that represent something from this past year.

Activists at a protest in Guinea, September 2018. (Courtesy of Nomi Dave)

“Despite Zoom life and everything else, the students have been so impressive with all their ideas and engagement,” she said.

Next year, Dave will teach a new civic engagement course, “Amplified Justice,” connected to a collaborative project she’s working on with Coughlin and music professor Bonnie Gordon. The project and the course will explore sound, voice, protest and gender. Students will have an opportunity to work on the collaborative project, she said.

Both “Amplified Justice” and the film on the Guinean journalist are part of an initiative Dave has dubbed the “Sound Justice Lab,” which received initial funding from the UVA Equity Center and aims “to bring together students and faculty bridging law and the humanities at UVA, with a focus on questions of justice in everyday life.”

Sounds like we’ll be hearing more about these projects in the future.

Media Contacts

University News Associate Office of University Communications

anneb@virginia.edu (434) 924-6861