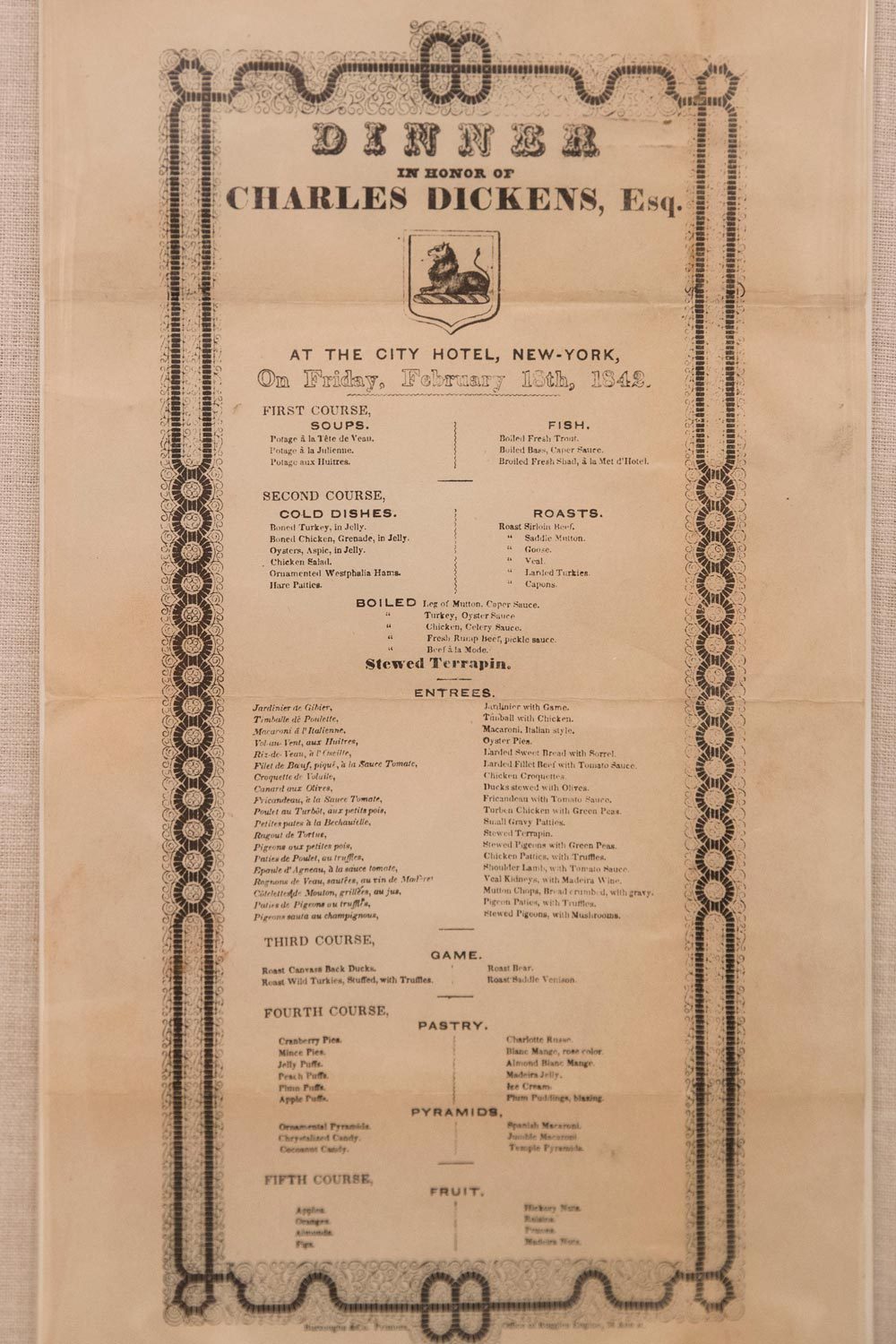

The University of Virginia’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library has a menu from a dinner held in New York City in honor of Charles Dickens during his 1842 tour of America. On display in an exhibit at the library, that extensive menu includes stewed pigeons – meaning the passenger pigeon.

Finding Extinction Where You Least Expect It – In the Special Collections Library

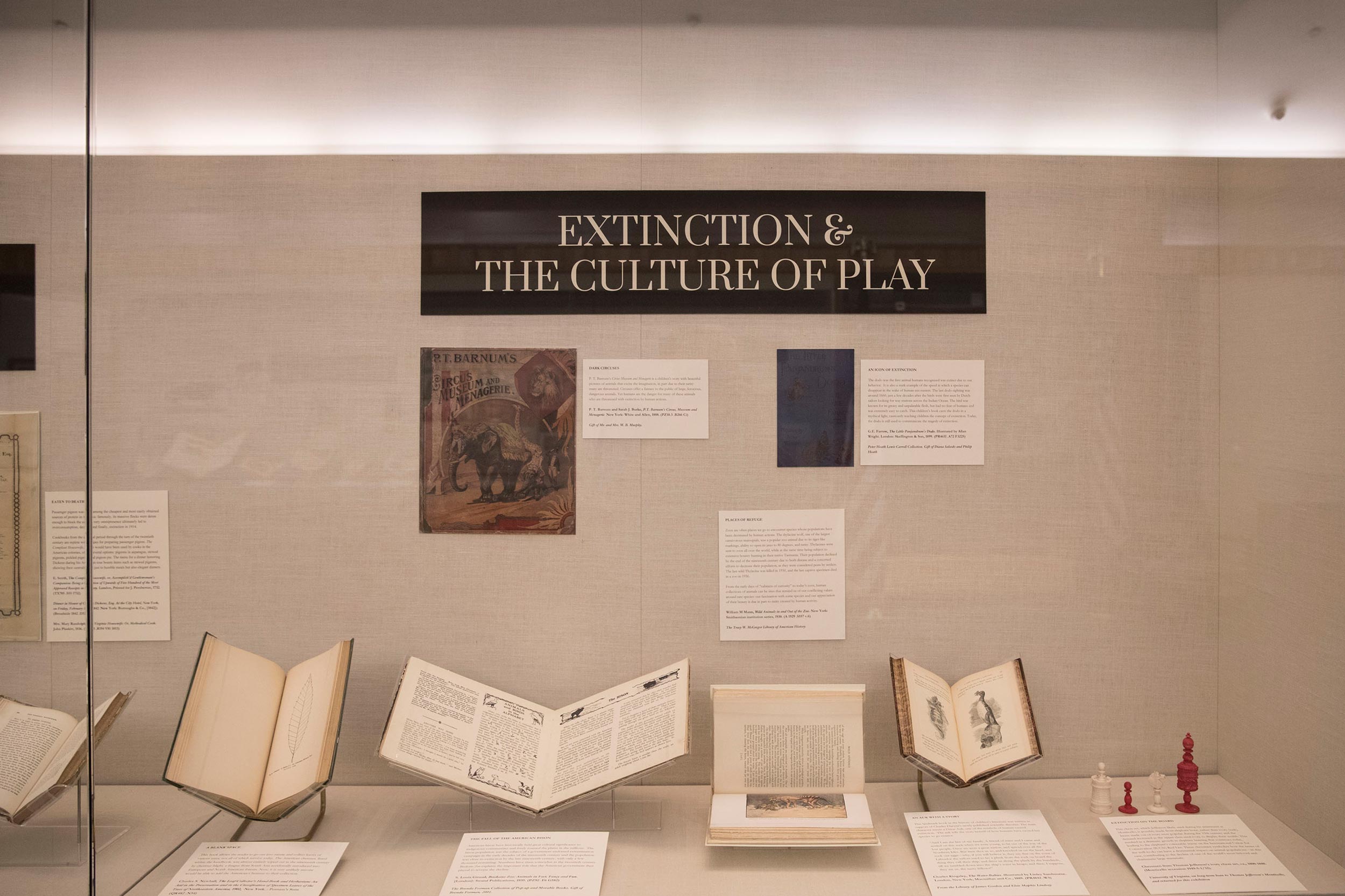

Students curated “Extinction in the Archive” to show materials that document processes of manmade extinction, but often are not understood as such. (Photos by Dan Addison, University Communications)

No one has seen a passenger pigeon for more than a century, but many people have heard of them. Once the most numerous bird species in North America, they were said to darken the sky and create thunderous noise when they migrated in flocks of millions. They were shot or netted for sport and especially for dinner. Basically, they were eaten into extinction.:

This extensive menu for a dinner honoring Charles Dickens’ 1842 tour of America includes stewed pigeons – meaning the passenger pigeon, which was hunted and eaten into extinction.

“This is not only a document about Dickens and his American tour, and about the culinary history of America; it’s also a document in the history of extinction and biodiversity loss,” said Adrienne Ghaly, a postdoctoral fellow in the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences and visiting scholar in the English department.

Ghaly began teaching “Extinction in Art and Literature” as part of the New College Curriculum three years ago. She describes the course as an exploration of “how man-made, or anthropogenic, extinction is being conceptualized and represented in literature, visual art and other cultural artifacts … as an urgent conceptual, representational and ethical problem.”

“The current biodiversity crisis is actually hard for most people to see and experience in their everyday lives,” Ghaly said.

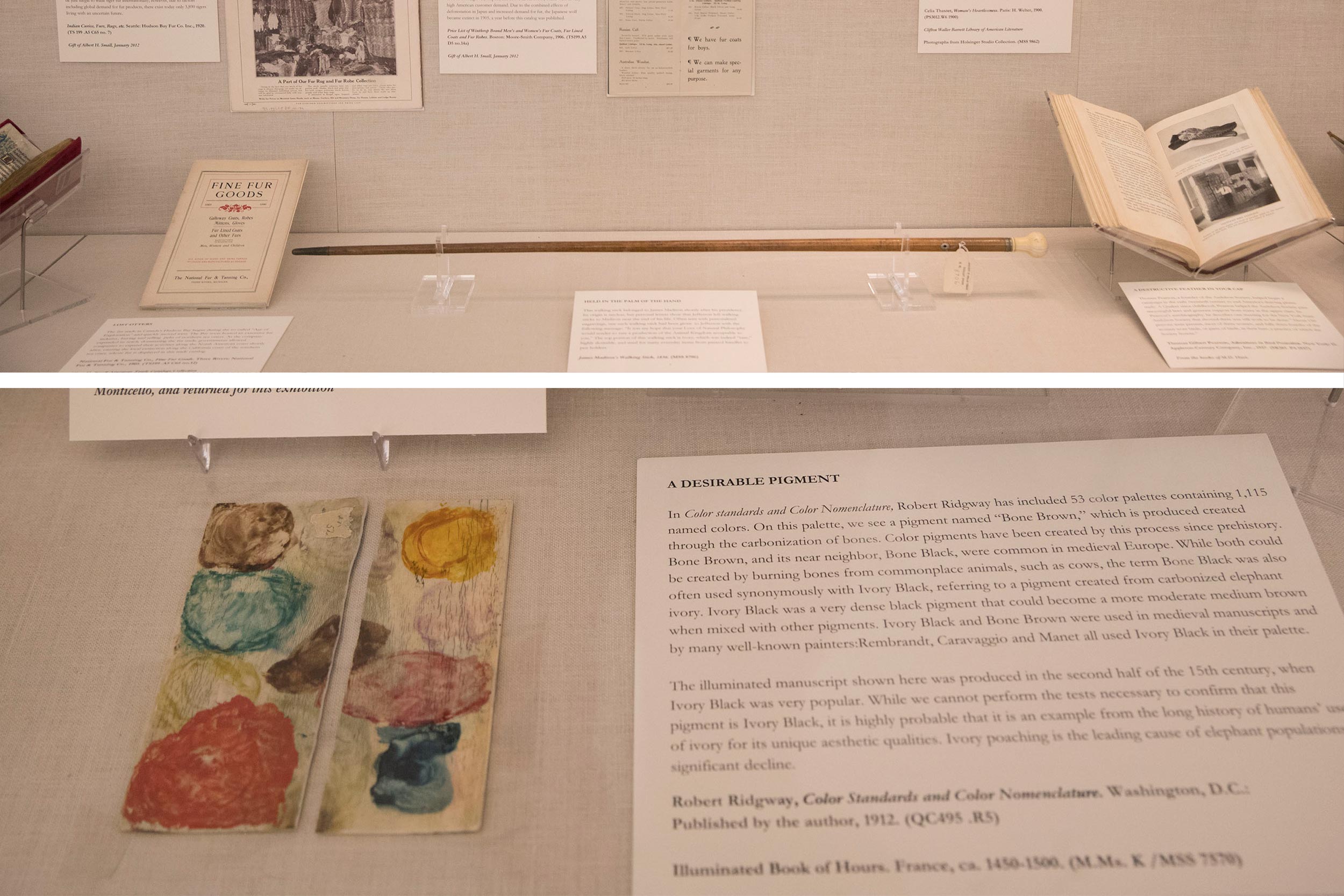

Last year, she asked several students if they would be interested in participating in a research project to look at the Special Collections Library’s holdings and identify materials that document processes of manmade extinction, but often are not understood or catalogued as such, she said. Their work has culminated in the Special Collections exhibition, “Extinction in the Archive,” which will remain on display in the first-floor gallery of the Harrison/Small building until Jan. 18.

“This was an involved process, identifying areas of possible interest such as trade catalogs and botanical prints, travel narratives, cookbooks, menus of 19th-century Independence Day dinners, game pieces and books on painters’ pigments,” Ghaly said of the students’ research.

“The main goal of the project was to create an exhibition to raise awareness about our continual complicity in biodiversity loss over the last two centuries,” Liv Gwilliam, now a third-year student, said.

While she searched through Special Collections, Gwilliam said, “What was most notable was how conscious people were, even over 100 years ago, about the harm they were doing to animals while they were doing it. This was probably the greatest lesson I learned.”

Passenger pigeons were once the most numerous bird in North America, said to darken the sky and create thunderous noise when they migrated in flocks of millions.

For instance, Gwilliam found a letter from a woman who talks about her brother and other family members killing hundreds of wild pigeons.

The letter’s author, C.R. Cochran, “notes that they are hunting so many of the birds that they will likely get sick of eating them soon,” Gwilliam wrote in an email. “Realizations about overconsumption, overhunting, and unsustainable practices are all over the artifacts we found for the exhibition.”

She was “fascinated and passionately saddened by what she learned” about extinction in the course and in her research, said Gwilliam, who is double-majoring in the Global Studies Environments and Sustainability program and also the Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy. “Focusing on the issue from a humanities perspective allowed us to interrogate the ways in which humans interact with and think about animals, and these values and actions are at the root of why we are accelerating biodiversity loss.”

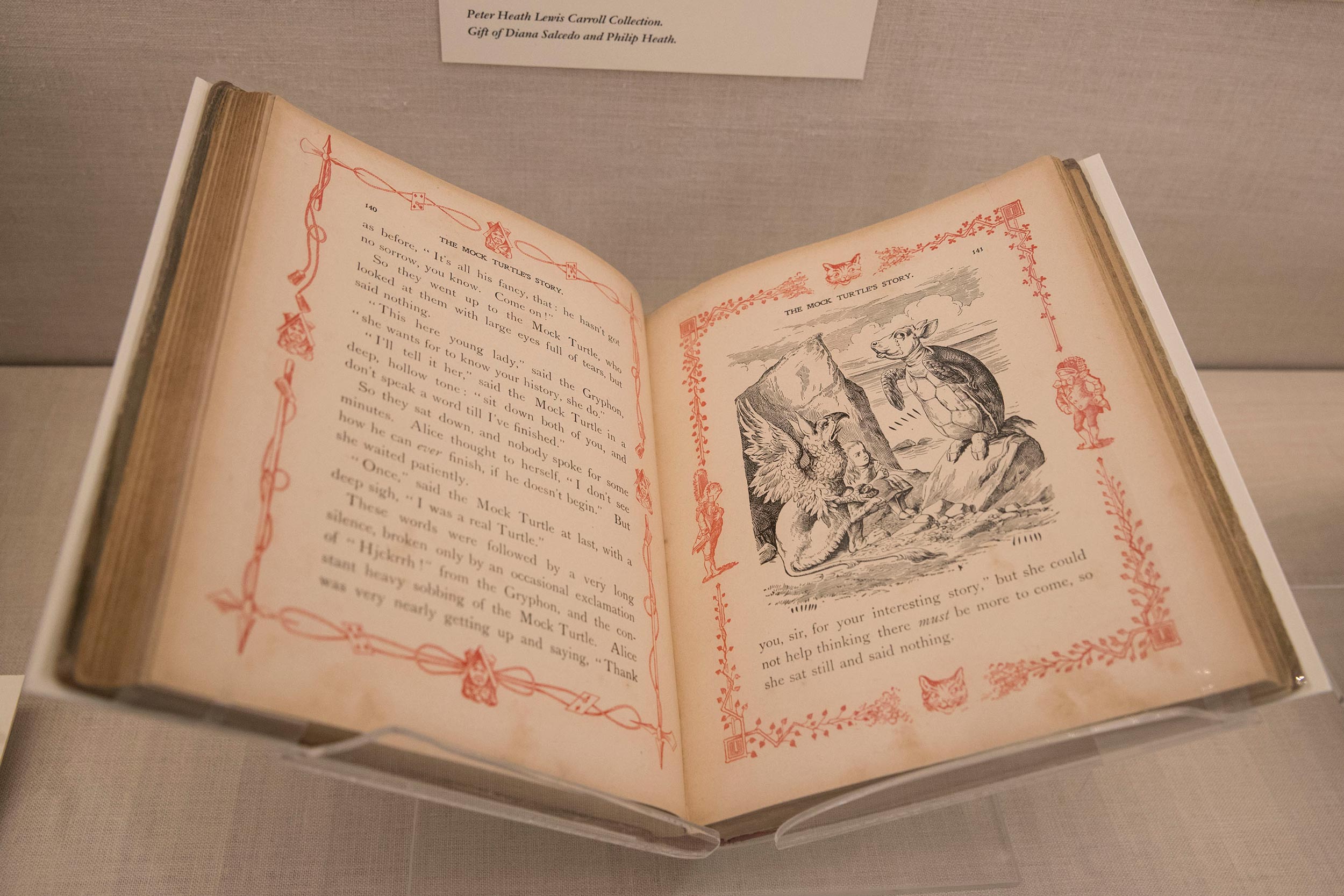

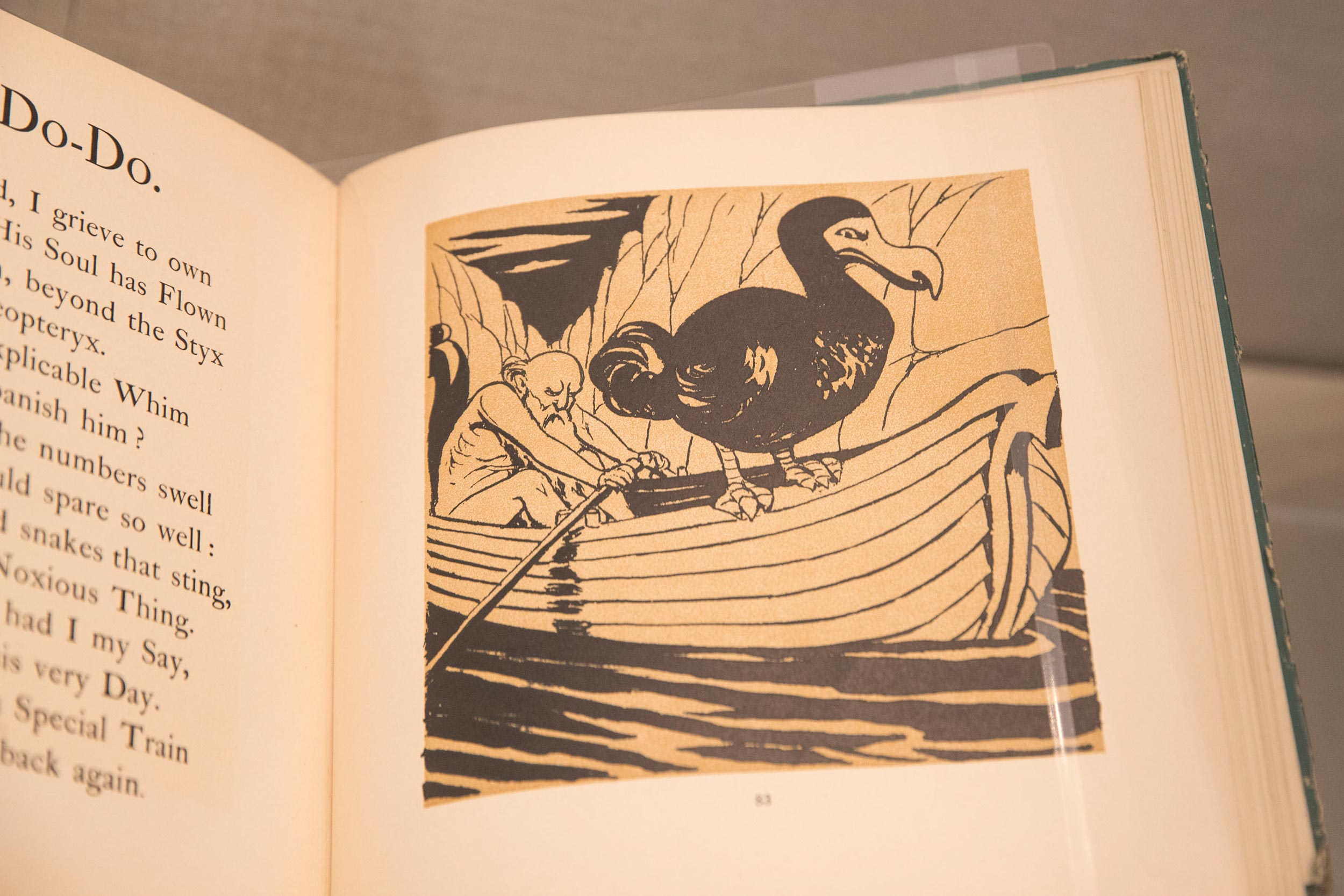

In “Alice in Wonderland,” Lewis Carroll imagines the mock turtle as a real animal. Mock-turtle soup was created in the 18th century after the vogue for turtle soup at lavish dinners led to serious declines in turtle populations in many locations. Mock-turtle soup was made using a calf’s head or pigs’ ears. In the 1902 edition, artist John Tenniell draws the mock turtle with ears and a snout. Carroll also includes the extinct dodo bird in his book.

Skylar Wampler, another student in Ghaly’s course, also found items to display that she called “narratives of extinction that the author of the time did not know they were narrating.”

A third-year student majoring in the English department’s Area Program for Poetry Writing, Wampler, who’s minoring in environmental sustainability, said, “I learned so much from this project. …The exhibit really helped me to understand how both studies [poetry and environmental sustainability] are interdisciplinary.”

Looking at books about plants, Wampler found evidence of how invasive species could be a cause for the extinction of another plant, or how popularity and transplantation could endanger a species. The Venus flytrap, for example, is native to a coastal section of North Carolina and South Carolina, but is now endangered in the wild, despite being the most common cultivated carnivorous plant.

Wampler also wanted to include something related to extinction of plants, even though she knew it would be “most difficult to encourage empathy for a dying moss,” she wrote in an email. “Most people tend to focus on ‘charismatic megafauna’ and ignore the smaller (and equally important!) species such as a flower or algae.” Charismatic megafauna refers to popular large animals like the giant panda and elephants.

A recent United Nations report predicts about a million species are on the path to extinction, many in the coming decades, Ghaly said. “How do we understand this historical moment if it’s happening all around us, but we can’t see or experience it? Art and literature can show us ways of thinking about it in everyday life,” she said.

“This urgent, global and contemporary crisis is often described not only as the destruction of animals and plants, but also as the destruction of knowledge, as ‘burning the library of life,’” Ghaly said. Thus, she and colleagues Willis Jenkins, professor of religion, ethics and environment and convener of Environmental Humanities at UVA, and English professors Elizabeth Fowler and Mary Kuhn, organized a symposium, “Burning the Library of Life,” on species extinction and the humanities, held as part of UVA’s Environmental Humanities Week at the end of September.

The Special Collections exhibit opened Sept. 27 in conjunction with the symposium. The Special Collections Library supported the students with Wolfe Undergraduate Fellowships, a program that offers undergraduate students the opportunity to develop an outreach or research project that promotes the library’s resources to the University community and wider public, according to exhibitions coordinator Holly Robertson, who, along with curator Molly Schwartzburg, worked with the students.

The Small Special Collections Library has been partnering with faculty to offer experiential learning experiences for students with greater frequency over the past few years, Robertson said, including both undergraduate and graduate courses.

“It is a great introduction to primary research in Special Collections for undergrads,” she said. “Typically, these students select two to six items for an exhibition and do research to convey the story of those objects as pieces of the larger exhibition narrative. They obtain both curatorial and hands-on experience participating in the layout, design and outreach components of exhibitions and work with Molly on the research/curatorial angle and me on the exhibition design and layout end of things,” Robertson wrote in an email.

For the “Extinction” exhibit, the students researched in the archives from October to April and found dozens of potential texts and objects to include. Then each student developed a theme and curated five to seven objects displayed in that category. In addition to Gwilliam and Wampler, the student curators included Ryley Crow, Abby Harrell, Joseph Snitzer and River Whelan.

Wampler wrote, as in the past, so, too, in the present: “It’s very interesting to me to see how species extinction is present in our reality underneath our daily awareness. Most people do not conscientiously look for the extinction of insects or plant species in their daily lives, but the reality of death is all around us (sorry to sound so morbid).”

Added Gwilliam, “I think that the exhibit is powerful because it highlights the mistakes we made in the past in order to mobilize people to not make them again now and in the future. In 100 years, we don’t want people to look back at our literature, see that we knew the harm we were doing, and wonder why we didn’t do anything to stop it.”

Media Contacts

University News Associate Office of University Communications

anneb@virginia.edu (434) 924-6861