Nov. 10, 2006 -- The homestead of Catherine “Kitty” Foster, a free black woman who lived near the University from 1833 to 1863 on Venable Lane, will be preserved as a one-acre park near U.Va.’s South Lawn project. The footprint of the house will be marked by shadow lines and the 32-grave cemetery next to it will be outlined in local stones.

Foster, a seamstress who also did laundry for the University’s faculty and all-male student population in the early to mid-19th century, bought the property in 1833 and her descendants lived there until 1906. Twelve of the graves were discovered in 1993 during excavations for the expansion of the B-1 parking lot, and then 20 more were found in 2005 while archaeologists were examining the site for a Foster memorial to be incorporated in the South Lawn

extension. It is assumed some of the graves belong to Foster’s descendants, but there are no headstones and no way to determine if Foster herself is buried there.

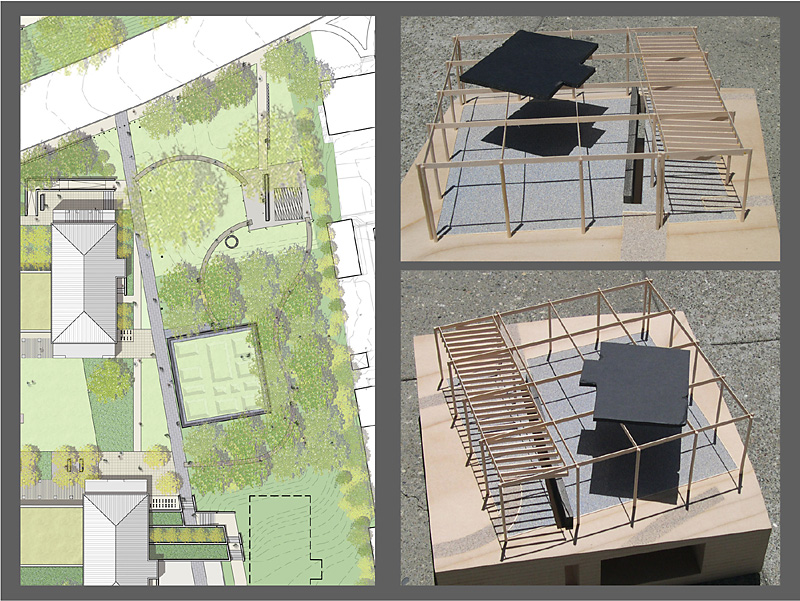

The house site will be marked by a “shadow catcher,” a device the size and shape of the footprint of Foster’s house, which will mark the building's outline in shadow lines, the thickness of which will change with the seasons and the position of the sun. An on-site, pole-mounted light will cast shadows after dark.

“It’s a creative way of interpreting the site without unearthing the artifacts,” said University Architect David J. Neuman. The artifacts from the house, including remnants

of floorboards and the foundation, are being left in the ground at the site.

“We are preserving the site below ground to protect it in its cultural context,” said Mary V. Hughes, landscape architect for the University. “That will allow future generations,

which may have more knowledge or better technology, to explore the site.”

“The shadow catcher will be made of polished aluminum so it will sparkle and reflect light,” said landscape architect Walter Hood, of Oakland, Calif., who worked with architect Cheryl Barton of San Francisco in designing the park.

The shadow catcher has a conceptual relationship with the house site and the grave, Hood noted. While the internment in the earth is symbolic of the past, a bright light in the sky represents the future.

Hood has used shadows in memorials around the country. He has interpreted a variety of African-American historical sites, each one differently, according to Neuman.

The shadow catcher is held about 12 feet off the ground by a “trellis,” 40 feet by 40 feet, that will impose a shadow grid on the site. A faculty committee, including experts in African-American history, has been advising the architect’s office on the design and interpretation of the site throughout the process.

“People will be able to walk under” the trellis, Hood said. “I can see classes having seminars there. I can also see someone just sitting and pondering.”

Having the Foster house site and cemetery next to the South Lawn Project offers “a chance to connect to the African-American history, which has been neglected and even buried for so long," said Edward L. Ayers, dean of the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences, at the South Lawn groundbreaking ceremony on Sept. 29. “One of the things that I’m most excited about is the wonderful acknowledgement of that history that we’ll be able to do on the South Lawn.”

The cemetery portion of the property has been mapped and will be marked off by a low stone wall.

“We wanted to create a groundwork over the graves,” Hood said.

“The graves are preserved on-site and will not be disturbed,” Hughes said.

The Foster property originally covered about 2 1/8 acres, with a stone-paved work yard and outbuildings. Hughes said that Foster and her daughter were seamstresses and laundresses. In the last quarter of the 19th century, the area where they lived, now across Jefferson Park Avenue from the University, was populated largely by blacks and was referred to as “Canada.”

Foster, a seamstress who also did laundry for the University’s faculty and all-male student population in the early to mid-19th century, bought the property in 1833 and her descendants lived there until 1906. Twelve of the graves were discovered in 1993 during excavations for the expansion of the B-1 parking lot, and then 20 more were found in 2005 while archaeologists were examining the site for a Foster memorial to be incorporated in the South Lawn

extension. It is assumed some of the graves belong to Foster’s descendants, but there are no headstones and no way to determine if Foster herself is buried there.

The house site will be marked by a “shadow catcher,” a device the size and shape of the footprint of Foster’s house, which will mark the building's outline in shadow lines, the thickness of which will change with the seasons and the position of the sun. An on-site, pole-mounted light will cast shadows after dark.

“It’s a creative way of interpreting the site without unearthing the artifacts,” said University Architect David J. Neuman. The artifacts from the house, including remnants

of floorboards and the foundation, are being left in the ground at the site.

“We are preserving the site below ground to protect it in its cultural context,” said Mary V. Hughes, landscape architect for the University. “That will allow future generations,

which may have more knowledge or better technology, to explore the site.”

“The shadow catcher will be made of polished aluminum so it will sparkle and reflect light,” said landscape architect Walter Hood, of Oakland, Calif., who worked with architect Cheryl Barton of San Francisco in designing the park.

The shadow catcher has a conceptual relationship with the house site and the grave, Hood noted. While the internment in the earth is symbolic of the past, a bright light in the sky represents the future.

Hood has used shadows in memorials around the country. He has interpreted a variety of African-American historical sites, each one differently, according to Neuman.

The shadow catcher is held about 12 feet off the ground by a “trellis,” 40 feet by 40 feet, that will impose a shadow grid on the site. A faculty committee, including experts in African-American history, has been advising the architect’s office on the design and interpretation of the site throughout the process.

“People will be able to walk under” the trellis, Hood said. “I can see classes having seminars there. I can also see someone just sitting and pondering.”

Having the Foster house site and cemetery next to the South Lawn Project offers “a chance to connect to the African-American history, which has been neglected and even buried for so long," said Edward L. Ayers, dean of the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences, at the South Lawn groundbreaking ceremony on Sept. 29. “One of the things that I’m most excited about is the wonderful acknowledgement of that history that we’ll be able to do on the South Lawn.”

The cemetery portion of the property has been mapped and will be marked off by a low stone wall.

“We wanted to create a groundwork over the graves,” Hood said.

“The graves are preserved on-site and will not be disturbed,” Hughes said.

The Foster property originally covered about 2 1/8 acres, with a stone-paved work yard and outbuildings. Hughes said that Foster and her daughter were seamstresses and laundresses. In the last quarter of the 19th century, the area where they lived, now across Jefferson Park Avenue from the University, was populated largely by blacks and was referred to as “Canada.”

Media Contact

Article Information

November 10, 2006

/content/foster-home-cemetery-remembered-memorial-park