Editor’s note: Marc Selverstone wrote this piece as part of the University of Virginia Institute of Democracy’s efforts to provide context around the 2020 presidential election and transition. You can read more on the institute’s “From Election to Transition” website. Selverstone is an associate professor of presidential studies at UVA’s Miller Center and chair of the center’s Presidential Recordings Program, which makes once-secret White House tapes accessible to the public.

P

residential transitions are among the most sacred, yet precarious moments in the American political lifecycle. The peaceful transfer of power from one administration to another has been a core principle of American democracy for well over 200 years. But transitions are also moments of inherent instability, with one set of officials heading for the exits and another one hitting the on-ramps. While outgoing and incoming administrations have long endeavored to effect smooth handovers, any number of developments, from the personal to the political to the geopolitical, can make it a perilous process.

As such, transitions involve a delicate dance in the best of circumstances. But transferring power amidst ongoing and intersecting national crises magnifies the challenge of ensuring effective governance and promoting the national interest – even more so when the change involves a transfer of power from one party to another.

The presidential transition of 1968 was one such moment. It took place against the backdrop of several shattering developments that year: the Tet Offensive and a deeply divisive war in Vietnam; the withdrawal of President Lyndon B. Johnson from the presidential race; the assassinations of civil rights icon Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Robert F. Kennedy; civil and racial unrest throughout the nation; and violent altercations at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. To many Americans, the nation seemed to be unraveling.

Marc Selverstone chairs the Presidential Recordings Program at UVA’s Miller Center, publishing and analyzing White House tapes. (Miller Center photo)

For Lyndon Johnson, who soon would vacate the Oval Office, the transition also came with the knowledge that President-elect Richard M. Nixon, in late October, had sabotaged the start of peace talks in Vietnam, and with it the possibility that Democratic candidate Hubert H. Humphrey – the sitting vice president – might benefit and win the presidency. Johnson was livid, but he sat on the information rather than leaking it, fearing a host of troubles that might flow from that disclosure. Nixon was thus able to hang on, claiming 301 votes in the Electoral College to Humphrey’s 191, but winning only 43.2% of the popular vote to Humphrey’s 42.7% (third-party candidate George Wallace garnered close to 14%).

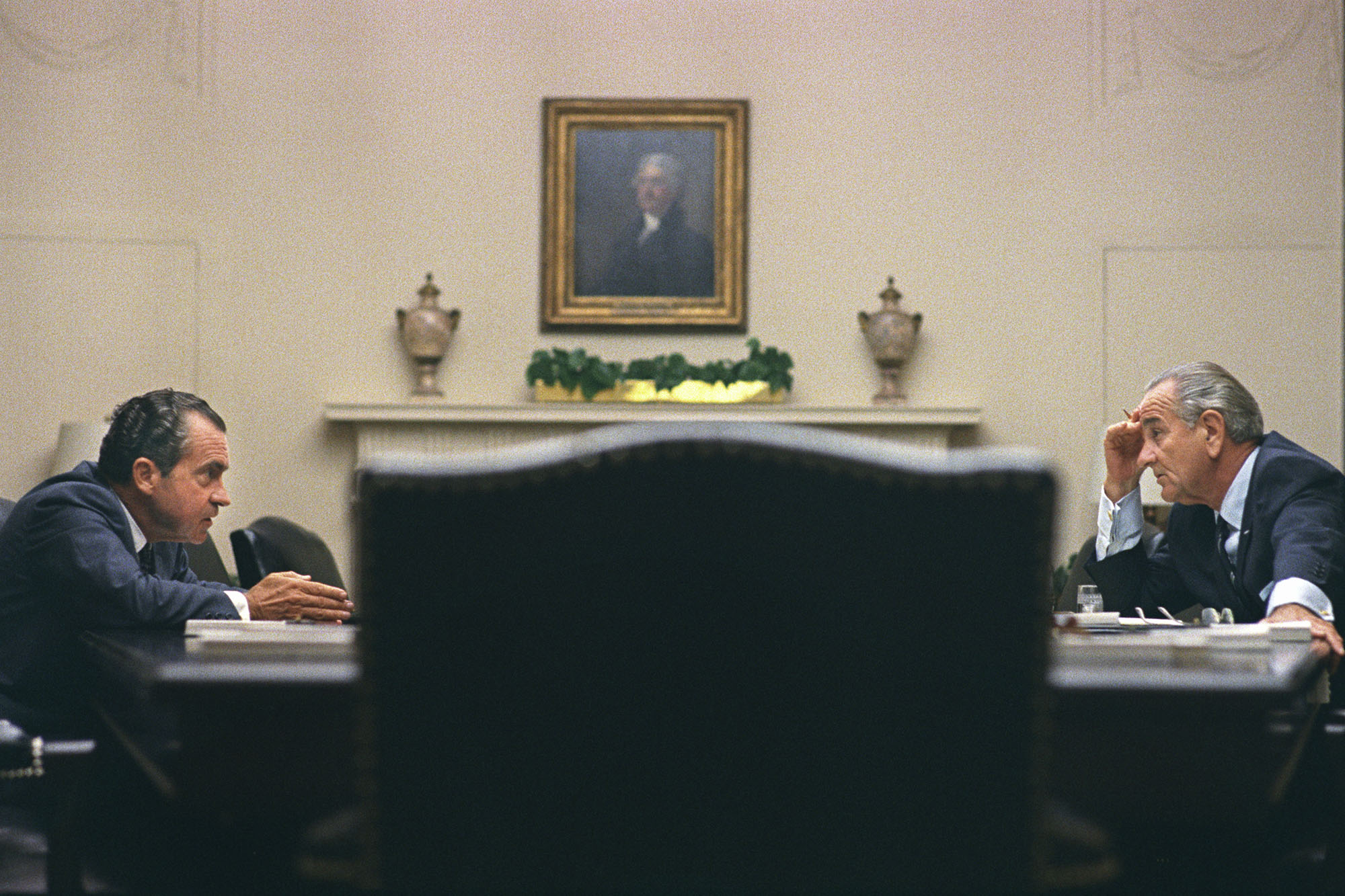

Nevertheless, the transition seemed to be proceeding apace. Nixon told Johnson, in a conversation captured by LBJ’s White House taping system, that he appreciated the cooperation he was receiving from Johnson personnel. And Johnson told Nixon what he had earlier said to Rev. Billy Graham and Nixon friend Sen. George A. Smathers (D-Florida): “that I would try to be as least – less partisan as I could and still be head of my party and be president, and I will try to be as helpful as I could when the inevitable happened, and we’re going to do that, and you’ll see that.”

Listen to and read the full transcript of this call at the Presidential Recordings Digital Edition.

So when Nixon briefed journalists just hours later on Nov. 14 that he not only needed to be “informed” of U.S. policymaking during the transition, but that he “agree” to any proposed “courses of action,” Johnson got his hackles up once again. The United States, Johnson told Nixon aides and Nixon himself, had only one president at a time. Still, there was a transition to manage, with the whole world watching. As the two principals acknowledged that morning, it was important that the outgoing and incoming teams be aligned, since the Soviet Union would

take advantage of you in an electoral period. They did in the [Dwight D.] Eisenhower-Nixon administration, in Laos, before [John F. “Jack”] Kennedy could get sworn in. [Nixon acknowledges throughout.] They did in ’62 in the Cuban Missile Crisis; October the 22nd, they moved. Now, they think we’ve got a gap.

But Nixon’s statement threatened to tie Johnson’s hands. According to Nixon, he simply wanted to emphasize that “any major policy decision that has to be implemented by the new president, the old – the previous adminis—, the present administration would want to clear it with the new administration to be sure it would be implemented.”

Johnson was having none of it. As he told the president-elect, “I’m very fearful if we leave the impression in the world that we have to check with [transition liaison Robert D.] Murphy or with you before we make a decision that we’re going to leave the impression we’ve got two presidents operating.” And just so audiences at home and abroad got the message, Johnson spoke to reporters the following day, affirming that “I will make whatever decisions the President of the United States is called on to make between now and January 20th.”

Listen to and read the full transcript of this call at the Presidential Recordings Digital Edition.

With that, that contretemps came to an end. But it highlights the recurrent challenge of policymaking during the interregnum, as well as the novelty of our present moment. For all of Nixon’s malfeasance, both then and later, and Johnson’s legitimate concern about an election that might have been improperly swayed, if not stolen, both sides pursued the time-honored and solemn tradition of transferring power in a professional, orderly fashion, with the nation’s interests in mind. Remarkably, the presidential transition of 1968, from the perspective of 2020, seems almost quaint.

Media Contact

Article Information

December 1, 2020

/content/how-1968-presidential-transition-compares-todays