To D’earth, jazz has a visceral, deep biological quality to it.

“Music is neurological,” he said. “Musicianship is neurological. And the pillars of musicianship are singing and drumming. [He snaps his fingers, beats his chest, slaps his thighs.] That’s musicianship. I am good with the drumming, bad with the singing.”

This, D’earth said, is the key to music.

“We only have seven notes in the major scale,” he said. “We only have 12 chromatic tones. We have centuries of music based on those notes. All different. How do you make it different? Rhythm. Where you put it. Everything is rhythmic. Sometimes it is a beat pattern.”

He swings his right arm in an arc in front of him.

“Is this rhythmic?” he said. “It is. It happened when it happened exactly when it happened. Rhythm is the frequency and duration of events – when stuff happens and how long it lasts. On that definition, rhythm is the ground of being.”

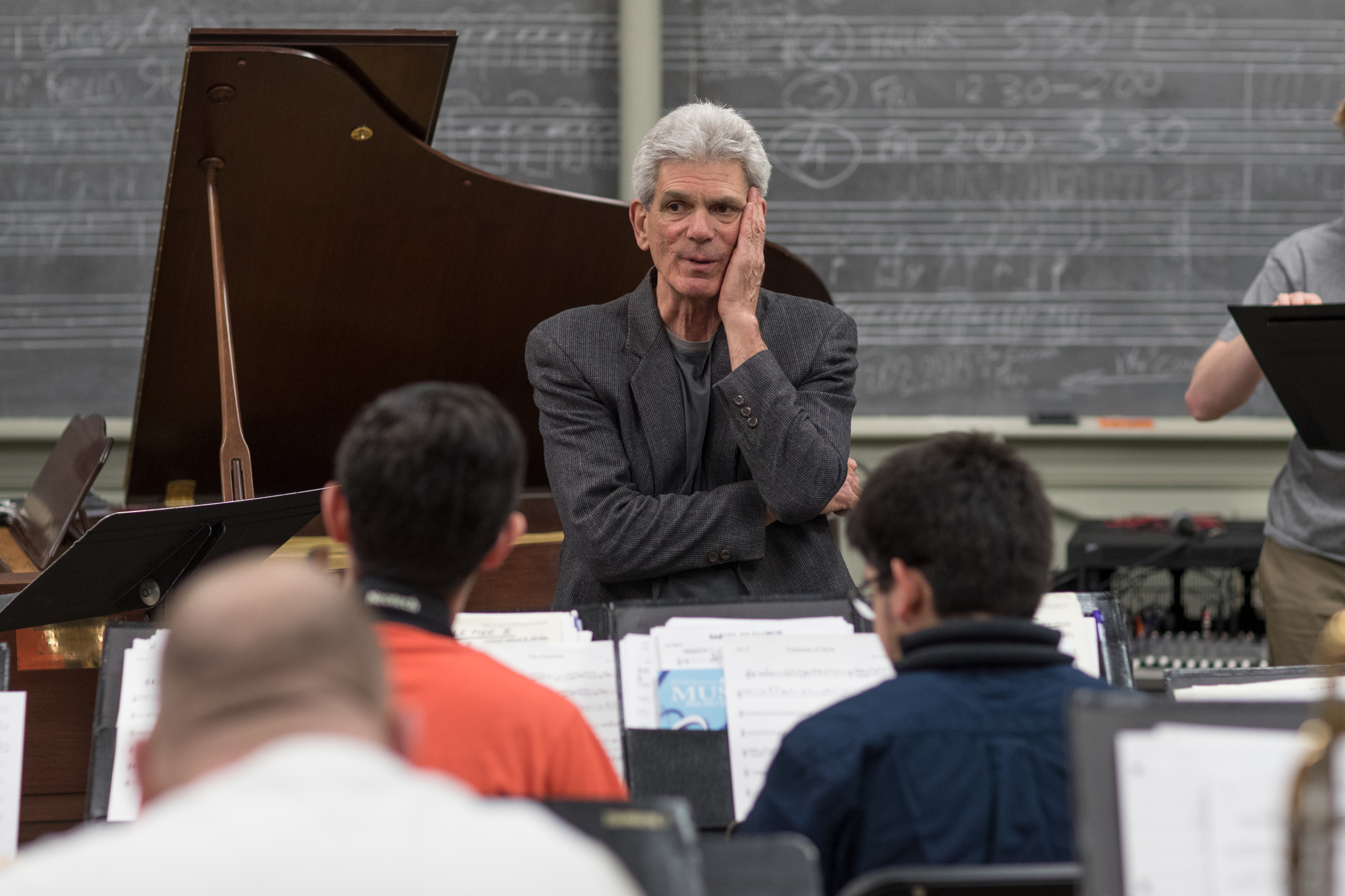

All of this factors into D’earth’s teaching: the history, the art, the nuance of the music.

“Basically, you have to tell them what the people had to go through to make the music. Then you tell them, ‘Listen to this,’ and then you tell them what to listen for,” he said. “It’s a rhythm section and it’s horns. There is melody, harmony and rhythm. And it is all based on rhythm.”

And it is based on individuality.

“Jazz gave music back to the musicians,” D’earth said. “Jazz teaches two things. Jazz teaches ‘own the music on your own instrument, in your own mind, in your own musicianship.’ The second lesson jazz teaches is Oscar Wilde’s encomium, ‘Be yourself. Everyone else is taken.’ The old jazz musicians said, ‘Tell your story.’ And they would actually be so offended if you were imitating somebody. I always warn my students that if they really want to play this music, they have to deal with themselves and they have to go to the music themselves, not have it mediated through some teacher.”

D’earth’s own musical education started with his father, who had an ear for the music, recognized reworking of old tunes and hated “phonies.” He loved Charlie Parker, while his contemporaries hated him.

His father started teaching him to play drums at age 2, and D’earth started with the trumpet at age 8. As he got good, really good, a certain teen-aged arrogance developed.

“I’m doing gigs,” D’earth said. “I got my union card when I was 14 years old. I’m playing with musicians, and the whole thing with musicians is they love you unconditionally, so you can’t help but to pass that forward if you have had that experience. I’m playing at the Newport Jazz Festival when I’m 17 years old. I mean, I’m thinking I’m pretty happening.”

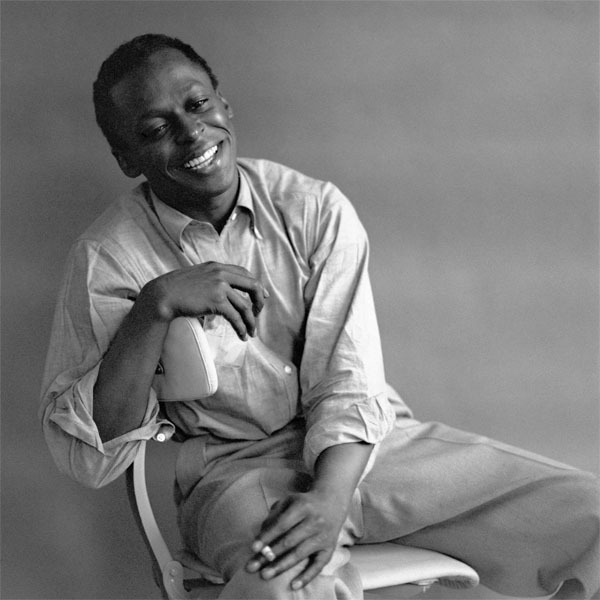

While thinking he was the center of it all, D’earth was out of step with many of his contemporaries because he rejected the work of John Coltrane, not liking it, thinking it noise.

“I am literally playing my Miles Davis record and picking the needle up over the Coltrane solo so I don’t have to listen to it,” D’earth said. “One night, I’m too lazy to get up and move this needle and his solo starts, which I had heard probably 20 times anyway and hated it, and it was like a conversion experience. I didn’t take it off this one night and BOOM! I heard it. And that’s when I learned what the difference was between hearing something and not hearing it.”