Early this month, President Joe Biden announced that the pharmaceutical company Merck would assist in manufacturing the COVID-19 vaccine produced by one of its main competitors, Johnson & Johnson.

In addition to reaffirming the Shakespearean adage that misery makes for strange bedfellows, the deal offers a window into the web of partnerships between public and private entities fueling the U.S. vaccine rollout – and the Biden administration’s goal of having enough vaccine for all American adults by the end of May. It also appears designed to help address further demand and some aspects of clinical uncertainties.

“This partnership was needed, and brings complementary capabilities together, but the push from the federal government was unusual,” said Vivian Riefberg, a health care expert and the David C. Walentas Jefferson Scholars Foundation Professor in the University of Virginia’s Darden School of Business.

Collaboration among pharmaceutical companies often occurs, Riefberg noted. French pharmaceutical company Sanofi, for example, is providing manufacturing support to Pfizer, which produces one of three COVID-19 vaccines currently approved for distribution in the U.S. And Merck is not without incentive – the Biden administration will pay the company $268.8 million to upgrade multiple facilities to produce the vaccine. Still, the deal struck Riefberg as unusual because of the active role the Biden administration took in pushing for a rapid deal.

Vivian Riefberg is a health care expert and the David C. Walentas Jefferson Scholars Foundation Professor at Darden. (Photo courtesy the Jefferson Scholars Foundation)

“I think it indicates a certain level of worry about the prevalence of COVID-19 infection we are still seeing in the country, as well as the advent of new variants that, even if they do not kill people in greater numbers, are still spreading the virus more quickly,” she said. “We are in a race to get more people vaccinated more quickly as well as supporting the potential of these vaccines to address variant challenges and the longevity of immunity. These are the things that appear to be at the heart of this deal.”

We asked Riefberg, who previously co-led consulting firm McKinsey & Company’s U.S. health care services practice and its American public sector practice, and her Darden colleague Andrew C. Wicks to analyze the new deal. Wicks, the Ruffin Professor of Business Administration and director of the Olsson Center for Applied Ethics, teaches a case study on Merck in some of his business ethics courses.

Ethics at Work

A case study that Wicks teaches, written by Stephanie Weiss and David Bollier, focuses on Merck’s decision in the late 1970s to test and manufacture a drug, later named Mectizan, that researchers thought might be effective in treating river blindness.

River blindness, found at that time in developing countries in Africa, parts of the Middle East and Latin America, is a devastating parasitic disease that worsens as larvae multiply and grow in the body, resulting in terrible itching, skin problems and eventually, blindness. There were many cases of victims driven to suicide, unable to stand their symptoms any longer.

The problem for Merck was that the patients who contracted river blindness and those who treated them did not have the money to pay for the drug Merck believed could solve the problem.

Andrew Wicks is UVA’s Ruffin Professor of Business Administration and director of the Olsson Center for Applied Ethics. (Photo courtesy Darden School of Business)

“There was no viable market, even though there was a tremendous need to treat this horrific disease,” Wicks said. Merck faced a decision: should they manufacture the drug and essentially donate it, forgoing profits?

Wicks points to a quote that George W. Merck, son of the company’s founder and its former chairman, had become known for: “We try to never forget that medicine is for the people. It is not for the profits. The profits follow, and if we have remembered that, they have never failed to appear.”

“They decided to proceed, even though no one lined up to pay for the drug,” Wicks said. “River blindness is now on the verge of being eradicated.”

That success story – and the reverence with which it is treated at Merck – offer some insight into the company’s willingness to help with COVID-19 vaccination efforts, even though their own efforts to develop a vaccine did not pan out.

“It gives us some context for thinking about our current problem, where we have this overwhelming human need for a vaccine,” Wicks said. “While initially it might seem counterintuitive to partner with a competitor, in this case it makes a lot of sense, and if you go back in Merck’s history you can see other instances where they have taken that larger view.”

It’s the kind of viewpoint that Wicks hopes his students at Darden develop – of business as an instrument for good, not just for profit.

“The world is complicated, and businesses don’t just fit neatly into the business sphere; they have to interact with governments and nonprofits and all kinds of stakeholders,” he said. “Firms and leaders must focus more on creating value in our world, rather than only seeing their narrow sphere of business and ignoring the rest. That is no longer a viable strategy, and I am not sure it ever was.”

A Bet on the Johnson & Johnson Vaccine – and a Faster Rollout

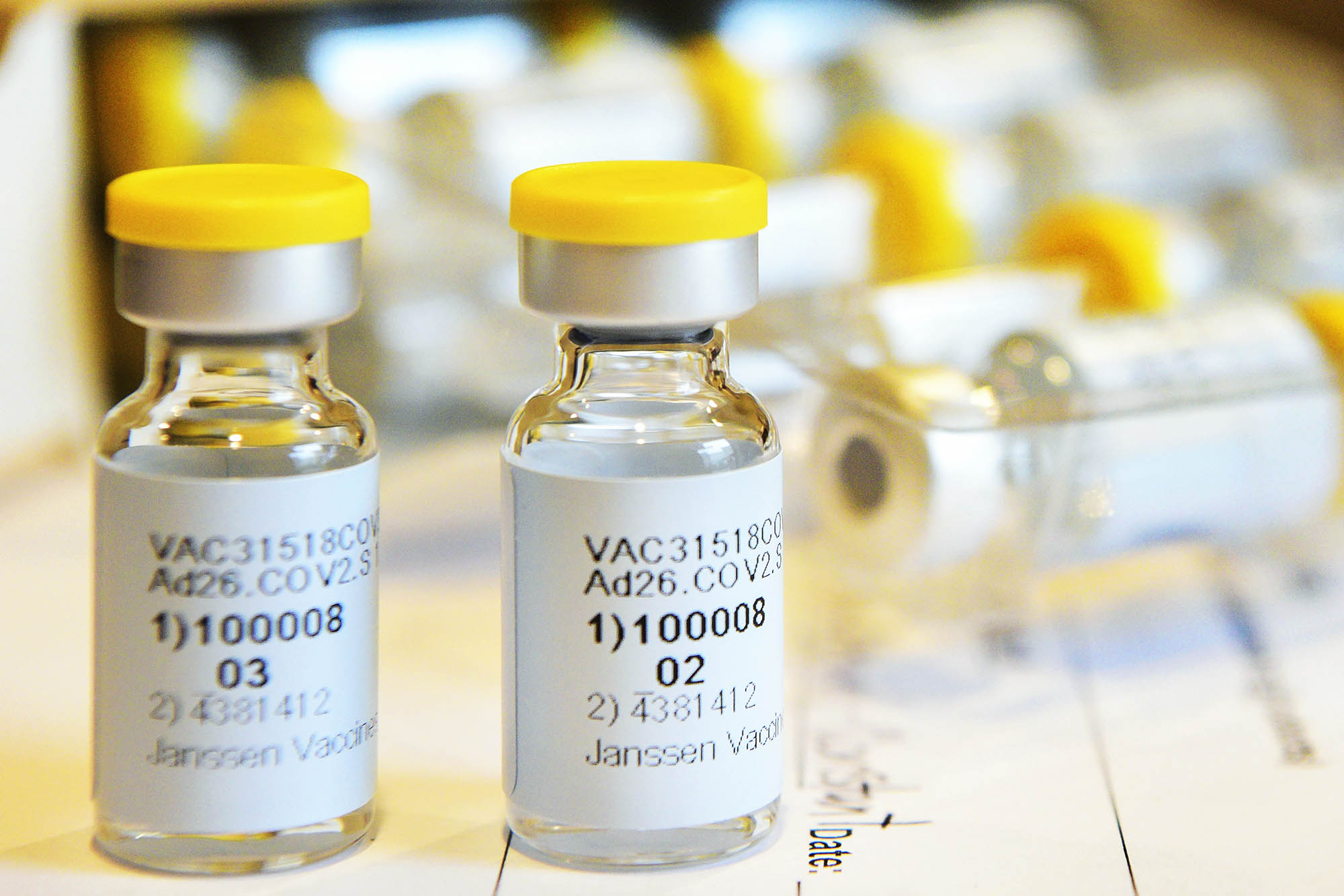

Riefberg, who in January outlined key challenges to the vaccine rollout, has long been keen on the Johnson & Johnson vaccine because its simpler refrigeration requirements and single-shot regimen – as opposed to the two-dose series required for the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines – could greatly streamline vaccine storage and distribution.

However, despite assistance from the U.S government’s Operation Warp Speed, begun during the tenure of former President Donald Trump, Johnson & Johnson was having trouble achieving anything beyond its basic obligations. In addition, with clinical uncertainties such as new variants appearing and questions remaining about the longevity of immunity, the need for expanded capacity to meet demand over time was increasing. The White House, now in the Biden administration, opted to step in to fully ensure greater demand could be addressed. In addition to finalizing the Merck deal, Biden’s team pushed Johnson & Johnson to shift to round-the-clock manufacturing and helped them supplement necessary supplies. On Wednesday, the White House announced that the Department of Health and Human Services would purchase an additional 100 million doses of the J&J vaccine by the end of this year.