As is custom at the start of a new year, many people resolved to sit around less and exercise more. In light of the global pandemic, this is as great an idea as ever, according to Arthur Weltman and Siddhartha Angadi, kinesiology professors in the University of Virginia’s School of Education and Human Development

“We know that being physically active and exercising regularly, as well as reducing sedentary behavior, are among the best things an individual can do to improve their health, quality of life and overall well-being,” Weltman said.

UVA Today caught up with Weltman and Angadi to learn, among many things, just how much exercise is the right amount to be of benefit, and how to safely return to pre-sickness exercise regimens after you’ve contracted COVID.

Arthur Weltman, left, and Siddhartha Angadi say sedentary behavior increases the risk of all-cause mortality and several diseases, including certain forms of cancer. (Contributed photos)

Q. In general, what are the benefits of regular physical activity?

AW: They include and are not limited to: reduced risk of all-cause mortality; reduced risk of developing coronary heart disease, stroke, multiple forms of cancer, type 2 diabetes, obesity, hypertension and osteoporosis; improved functional capacity, quality of life and ability to engage in activities of daily living; improved brain health and conditions that affect cognition, including depression, anxiety, dementia and Alzheimer’s disease; reduced risk of falls and fall-related injuries; and improved sleep.

Exercise is also an effective treatment for a variety of chronic diseases – oftentimes more effective than prescription medication – and comes with fewer side effects. Exercise that improves physical fitness – particularly cardiovascular and muscular fitness – conveys additional health-related benefits.

Q. What are the current recommended levels of physical activity needed to achieve these health benefits?

SA: They are 150 minutes per week of moderate intensity or 75 minutes per week of vigorous intensity activity (or an equivalent combination) and two or more days a week of muscle strengthening activities that work all major muscle groups – legs, hips, back, abdomen, chest, shoulders and arms. If you go beyond these basic recommendations, you will gain even more health benefits.

Q. How do you define sedentary behavior, and what are the risks?

AW: Sedentary behavior can be defined as any waking behavior associated with low levels of energy expenditure. For example, sitting, reclining or lying down.

The 2018 Physical Activity guidelines defined sedentary behavior to include sitting – leisure and/or occupational – television viewing or screen time, or low level of measured movement. Sedentary behavior independently increases the risk of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular disease mortality, type 2 diabetes and certain forms of cancer.

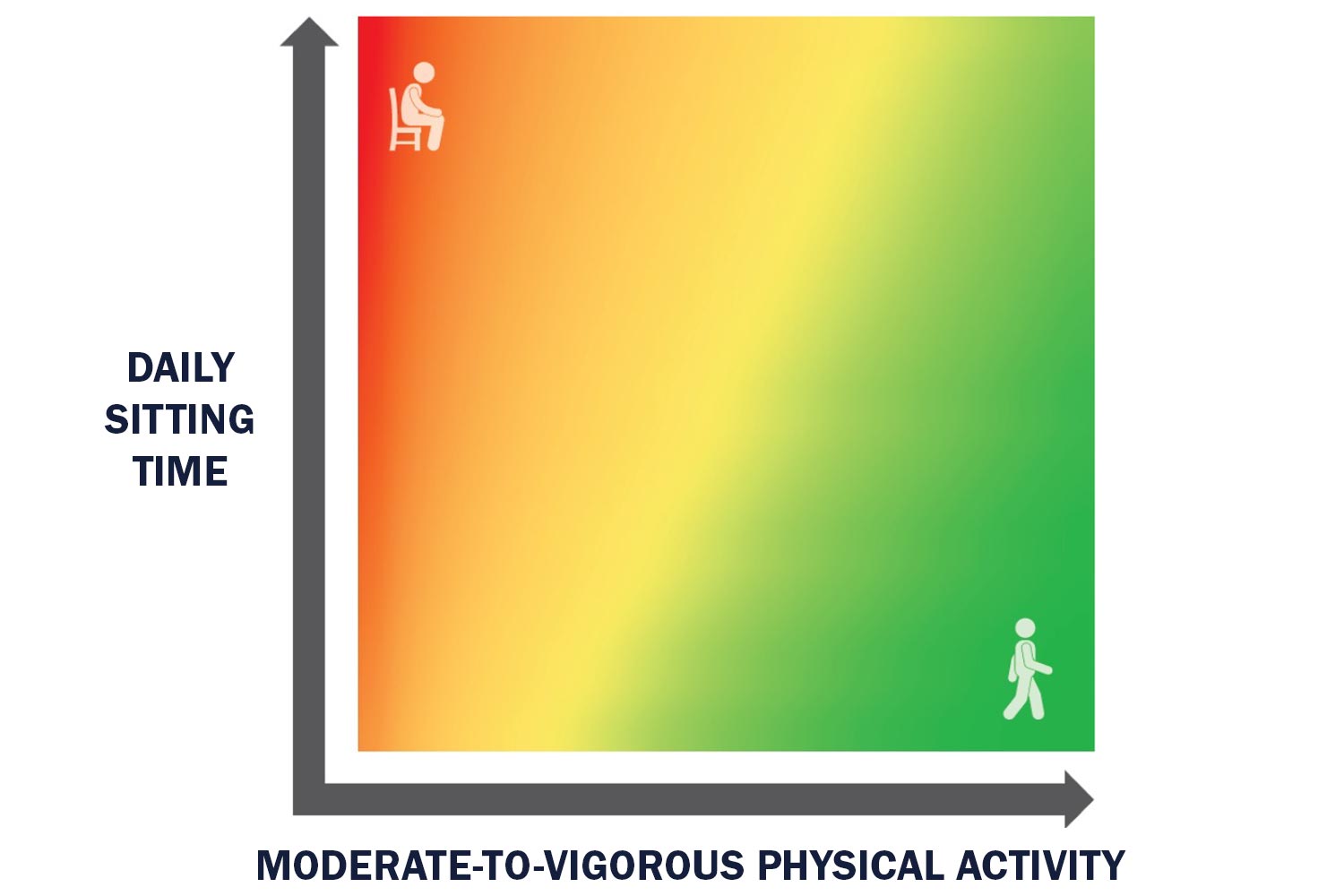

Risk of All-Cause Mortality in Adults

Risk of all-cause mortality decreases as one moves from red to green.

SA: The heat map above is taken from the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines (Figure 1-3). The vertical axis depicts sedentary behavior, and the horizontal axis depicts moderate to vigorous activity. As you can see, those who have a high amount of sitting time with low levels of moderate-vigorous physical activity (MVPA, top left corner) have the highest risk of all-cause mortality, whereas those with little daily sitting time and a high amount of MVPA have the lowest risk of all-cause mortality (lower right corner).

However, their findings suggest that even in those with high amounts of sitting time, the risk of all-cause mortality decreases as MVPA increases (top left to right) and at the highest levels of MVPA the risk of all-cause mortality is low, regardless of sitting time (top right). The current estimate for the volume of daily physical activity needed to lower risk is 60 to 75 minutes of moderate intensity or 30 to 40 minutes of vigorous-intensity activities.

Q. How does regular physical activity and exercise – if at all – impact the severity of COVID-19 symptoms?

AW: We want to state unequivocally that regular exercise is not a substitute for scientifically accepted preventive measures – vaccination, masking, social distancing.

That said, these were the results of the most comprehensive report to date by Robert Sallis and his colleagues, who identified 48,440 adult patients with a COVID-19 diagnosis from Jan. 1, 2020 to Oct. 21, 2020, who had at least three exercise vital sign measurements between March 19, 2018 and March 18, 2020.

- Patients with COVID-19 who were consistently inactive during the two years preceding the pandemic were more likely to be hospitalized, admitted to the intensive care unit and die than patients who were consistently meeting physical activity guidelines.

- Other than advanced age and a history of organ transplant, physical inactivity was the strongest risk factor for severe COVID-19 outcomes.

- Meeting U.S. Physical Activity Guidelines was associated with substantial benefit, but even those doing some physical activity had lower risks for severe COVID-19 outcomes, including death, than those who were consistently inactive.

Q. Did the authors have any recommended suggestions for the future?

AW: The potential for habitual physical activity to lower COVID-19 illness severity should be promoted by the medical community and public health agencies. And pandemic control recommendations should include regular physical activity across all population groups.