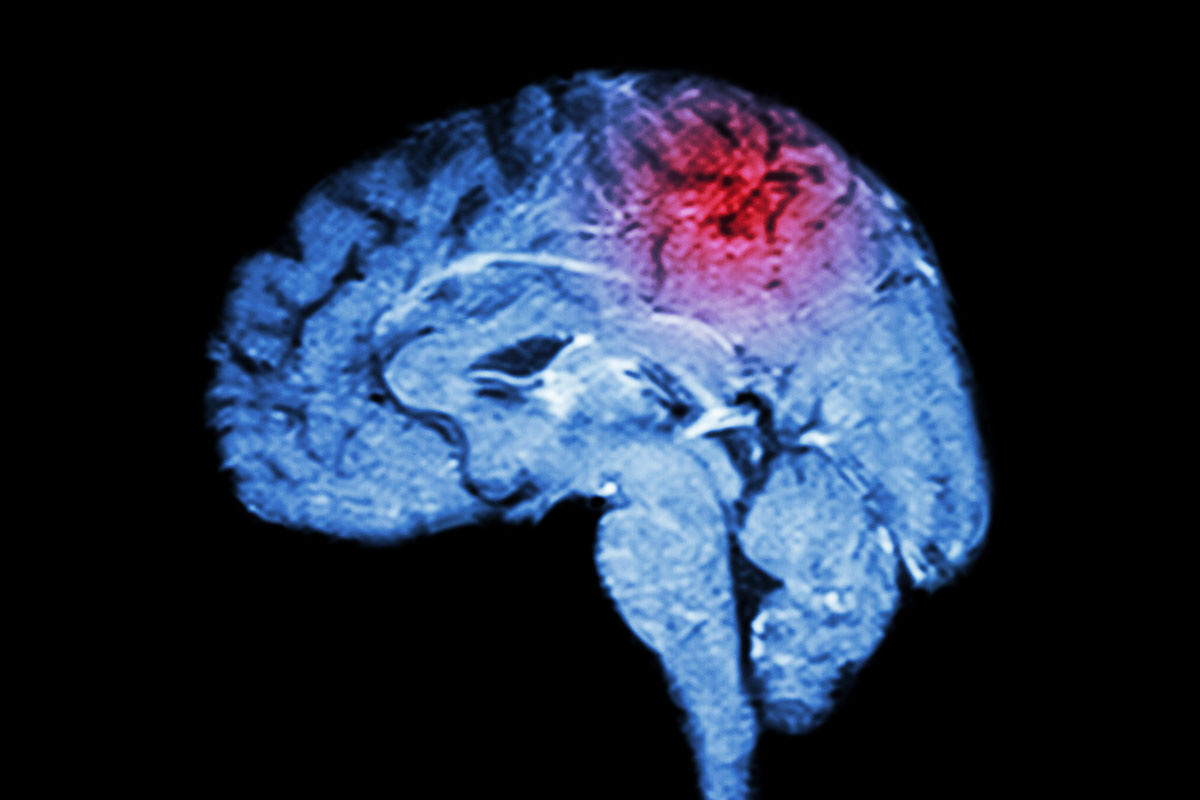

Ateriovenous malformations, the most common cause of strokes in children and young adults, are sometimes left untreated, but a sweeping new study strongly suggests that is generally a mistake.

The challenge that doctors have faced in treating patients with arteriovenous malformations – tangles of blood vessels prone to leaking and causing strokes – is that the treatment options are not without risk. So one approach commonly advocated has been to leave the condition unaddressed.

But the new study, led by the University of Virginia Health System and involving six other academic medical centers, has found the risks of treatment using Gamma Knife radiosurgery are often significantly outweighed by the ever-increasing risk posed by leaving the condition untreated. This is particularly true among patients diagnosed – as is typically the case – while they are teenagers or young adults.

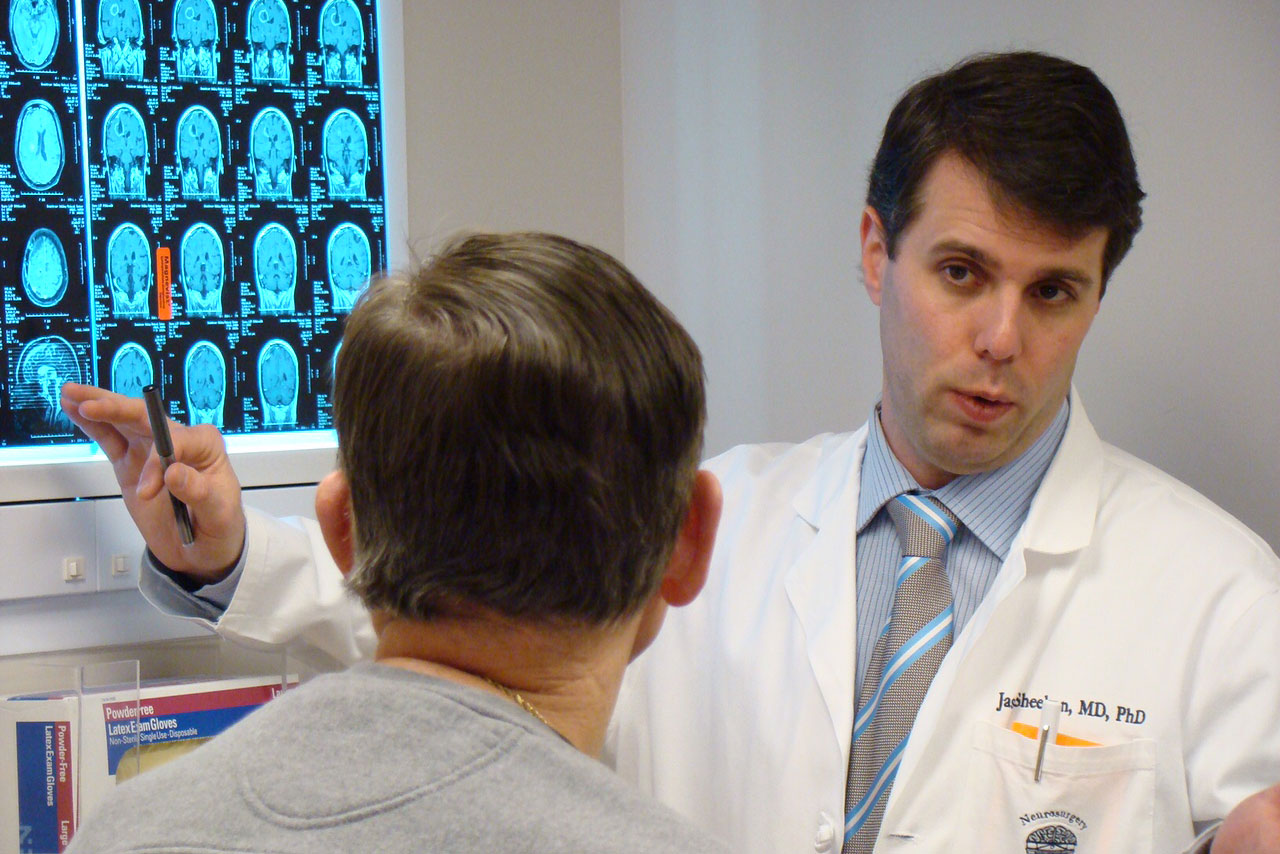

“These findings strongly suggest that patients who are younger are going to be far more likely to benefit from treatment than people who may be diagnosed later on in their life,” said neurosurgeon Dr. Jason Sheehan, director of the UVA Health System’s Gamma Knife Center. “If patients have at least a 10-year life expectancy, this new study strongly suggests treatment.”

Dr. Jason Sheehan, director of the UVA Health System’s Gamma Knife Center, said that younger patients have the most to gain from aggressive treatment.

“There’s a real uncertainty about the risk of stroke with these AVMs, but the general risk of stroke is thought to be about 1 [percent] to 3 percent per year,” Sheehan said. “When you factor that in over a 10-year period of time, you are talking about somewhere in the order of 10 to 30 percent risk of stroke, and that’s just the beginning if you’re diagnosed as a pediatric patient or a young adult.”

He noted the grim statistics physicians and patients – and, often, young patients’ parents – must consider in deciding to leave a malformation untreated: “If it ruptures, and the odds of it rupturing within the lifetime of a teenager are very high, the risk of death … is thought to be about 10 percent. So with each rupture, it’s about a 10 percent risk of dying, and that’s not even including the problems that can arise if it ruptures but doesn’t cause death: seizures, weakness, blindness and other neurological deficits.”

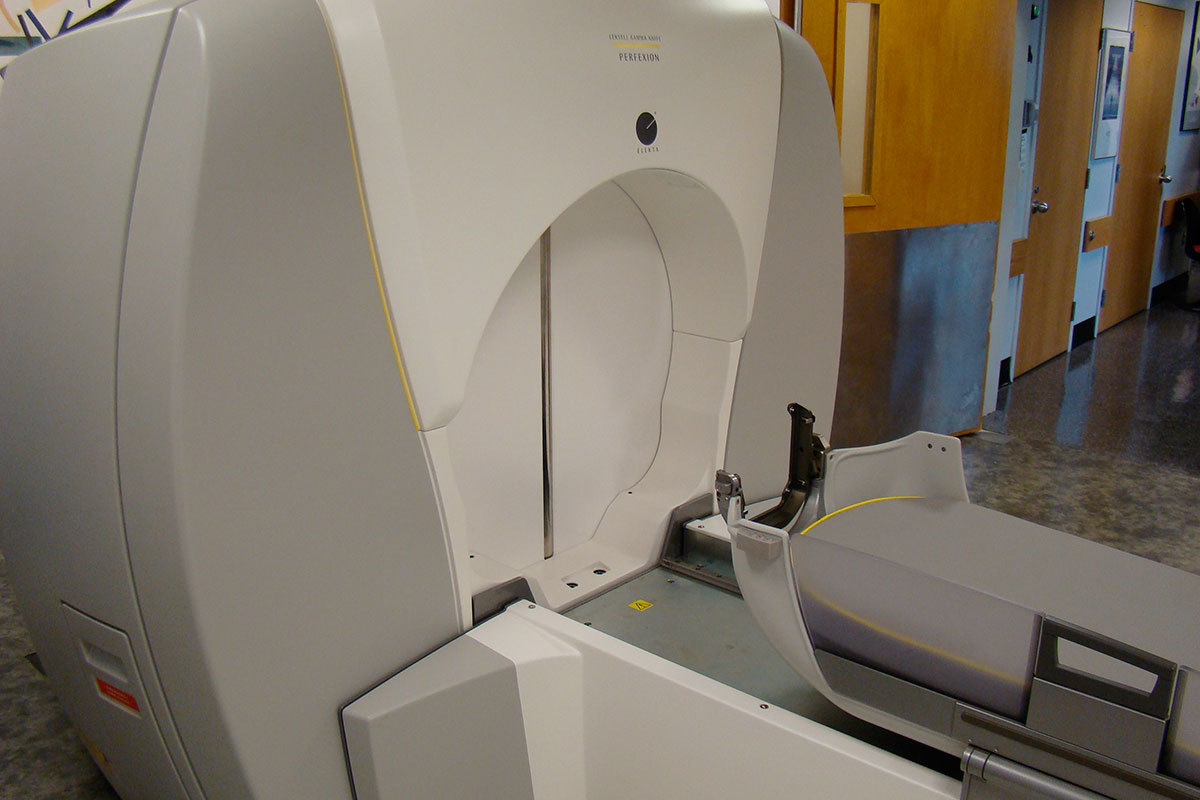

Gamma Knife radiosurgery, on the other hand, can close off arteriovenous malformations using fine beams of concentrated gamma rays, so that surgeons do not need to cut into the head. Approximately 80 percent of malformations can be closed off with this technique. However, it typically takes two to three years for the malformation to close fully after the procedure, and the risk of stroke remains during that time.

Although the non-invasive Gamma Knife has risks, it is less risky than doing nothing over the long term, according to the study.

Because of the complexities patients face, Sheehan urged them to discuss their options with a neurosurgeon who can evaluate their specific case. But for younger patients, he said, the new study offers a compelling argument for treatment. “If conservative management meant a risk-free approach for these patients, that is what we would recommend to them,” he said. “Unfortunately, that is not the case for many AVM patients. The stroke risk, even if it’s low on an annual basis, really begins to add up when you consider 10-year or more life expectancy. And in many of these patients, they exhibit 50 or more years of life expectancy.”

Sheehan and his colleagues have detailed their findings in an article in the scientific journal Stroke.

Media Contact

Article Information

March 8, 2016

/content/leading-cause-stroke-young-going-untreated-and-it-shouldnt-study-finds