Just under the bricks of the University of Virginia’s Central Grounds lies a rich vault of Virginia’s history – and for some, the keys to unlocking their own personal history.

Library reference specialist Regina Rush estimates that about a third of the researchers who visit the University’s subterranean Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library are there researching genealogy. Still, it was years before she realized that clues to her own ancestry were beneath her feet.

Using state records of births and deaths, Rush had been looking into her father’s familial line, but was having trouble determining whether her family had been enslaved or free people of color prior to the Civil War. Then one day she had an enlightening conversation with her older cousin, Gloria.

“I was researching this other family that I thought may have enslaved my ancestors and my cousin said, ‘Honey, our people were owned by the Rives family,’” Rush recalled. “When she said that, it was like ‘Ding ding!’ because I knew we have tons of Rives family papers in Special Collections.”

Reference specialist Regina Rush stands with an 1851 Rives family ledger that lists clothing orders for her enslaved great-great-grandparents. (Photo by Sanjay Suchak)

The Rives were a prominent branch of the Cabell family and some of the wealthiest landowners in Virginia during the 18th and 19th centuries. Several generations of the family attended UVA, and Special Collections holds many of their family papers.

While Special Collections is not a genealogy-focused library, the potential for familial research is often a side benefit of the thousands of primary-source American history documents the library holds.

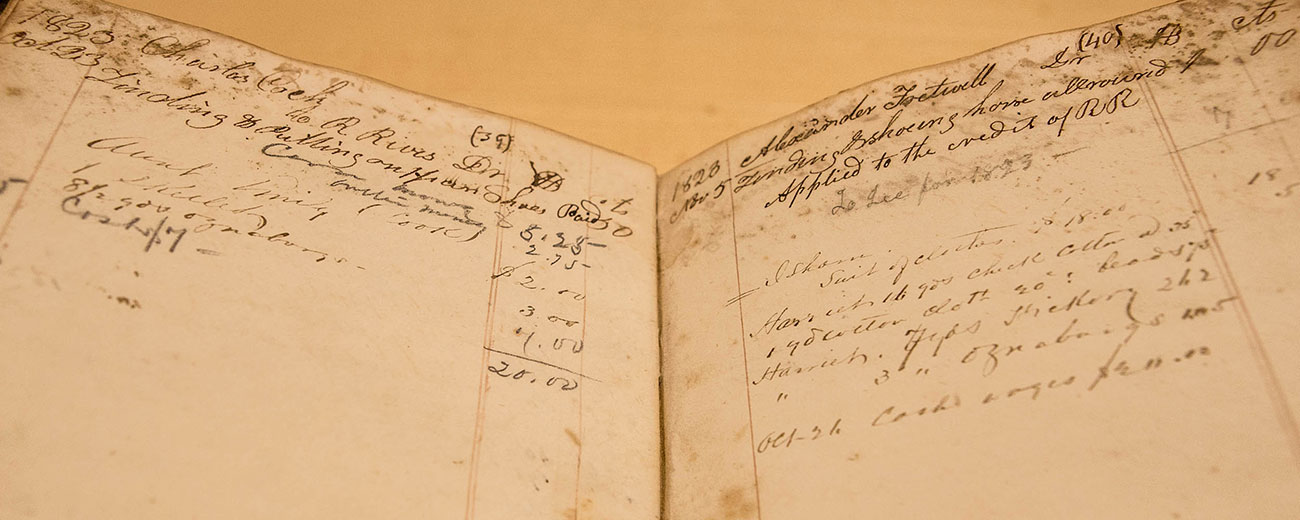

“Generally, what genealogy researchers use are what we call ‘family papers collections,’” Edward Gaynor, the librarian for Virginiana and University Archives, said. “These are collections of materials that were in the family for many years, like letters, financial documents and farm journals, and of course for antebellum years, there are lots of slave records.”

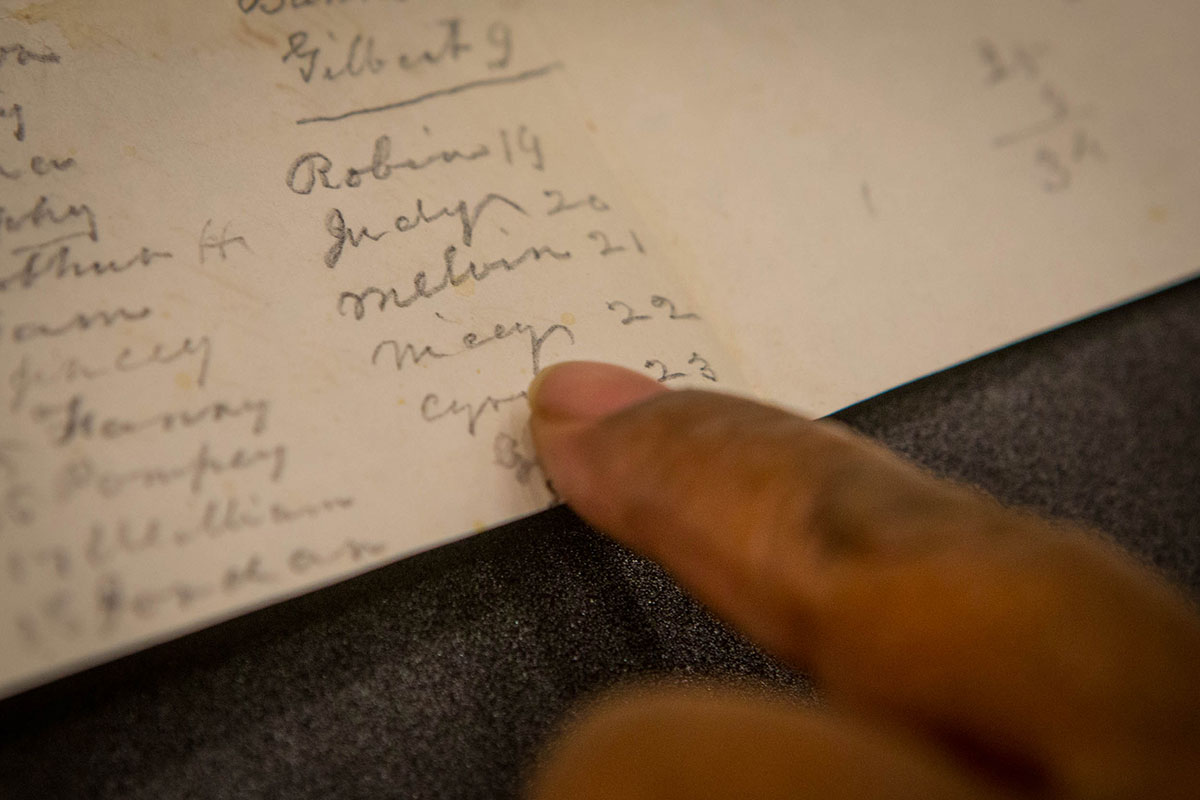

Rush first struck gold in her own search while studying letters to Robert Rives Jr. At the bottom of an 1851 missive from his sister-in-law, Rives wrote out a list of 34 names. A woman named Nicey – the same name that Rush knew belonged to her great-great-grandmother – jumped out at 22 on the list.

“I can’t tell you how emotional it was to make that connection,” said Rush. “I had found other official documents with her name, like census records and marriage records, but to actually go beyond those and be able to form a kind of a personal connection with her was really moving.”

Rush points to her great-great-grandmother Nicey’s name among a list of 34 slaves. It was the first mention of her she found outside of official government records. (Photo by Sanjay Suchak)

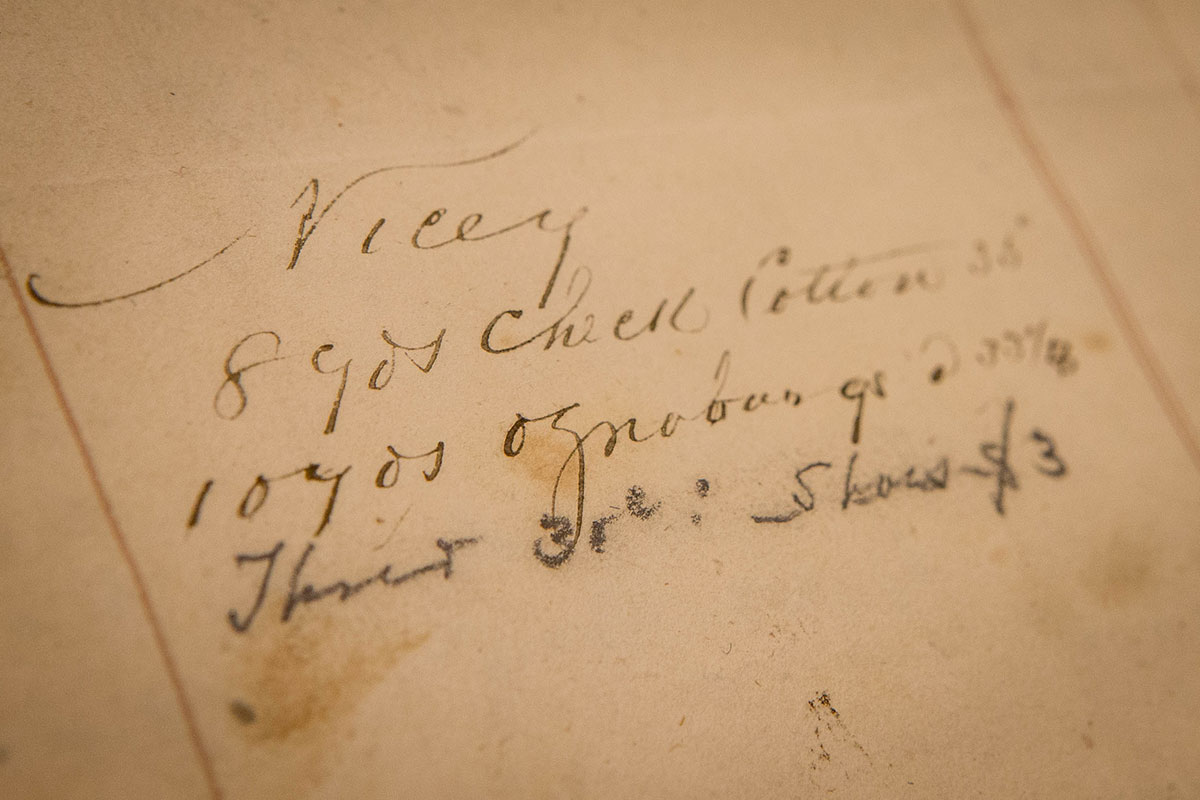

She found several other mentions of Nicey in the Rives’s ledgers, even one that lists her side-by-side with Rush’s great-great-grandfather, Isham Rush. Perhaps the most exciting of her discoveries was a ledger at the Scottsville Museum that had evidence that Nicey attempted to escape in 1851. A Sept. 20 entry in the Rives’ 1851 ledger shows that Robert Rives paid a local man $7.25 for Nicey’s apprehension and return.

Nicey’s foiled escape came just nine months after the birth of her child, Ella – Rush’s great-grandmother. Rush speculates that Nicey’s attempt was likely related somehow to her newborn daughter, but has yet to find hard evidence to back that up.

“Regina’s findings have been really amazing,” Gaynor said. “For years I’d heard that for African-Americans tracing their family, the trail just stops at 1865 if they were ever enslaved. I’ve since learned that’s not true, but I didn’t really understand how it was done until I saw just how much family structure Regina was able to turn up through documents like this.”

Rush added that it’s very important not to discount any potentially related documents when doing genealogy research, especially for African-Americans who are looking into antebellum years. It’s often the small mentions like she found in the Rives letters that can set a researcher on the path to bigger findings.

“Over the years, I’ve amassed tons of raw data through my research, and it’s just at this point I’m starting to put things together,” she said. “It’s like you have these skeletal remains of that life and these documents will flesh it out.”

Nicey’s name appears again, this time listed above an order for cloth to make her clothing. Her longtime partner, Isham, is listed on the next page above an order for a men’s suit of clothes. (Photo by Sanjay Suchak)

She also warns that some findings can be jarring.

“I think one of the most horrifying things I’ve found was at the Nelson County Courthouse. It’s an 1845 estate appraisement for Robert Rives Sr., and it lists all the slaves, including my great-great-grandparents,” Rush said. “They were appraised at values of $550 for Isham and $675 for Nicey and two of their children, Betsy and Sam.”

Seeing her grandparents listed at a monetary value, as if they were mere farm equipment, took Rush aback, but also made her all the more determined to find out the rest of their story.

While Isham’s fate remains unknown – he disappears from census records and is presumed dead after 1868 – Rush knows that Nicey lived to see emancipation and went on to marry a man named Paul Moseley. Additional census records from 1870 reveal that Rush’s great-grandmother, Ella, lived with her mother and new stepfather for a time and worked locally as a housekeeper.

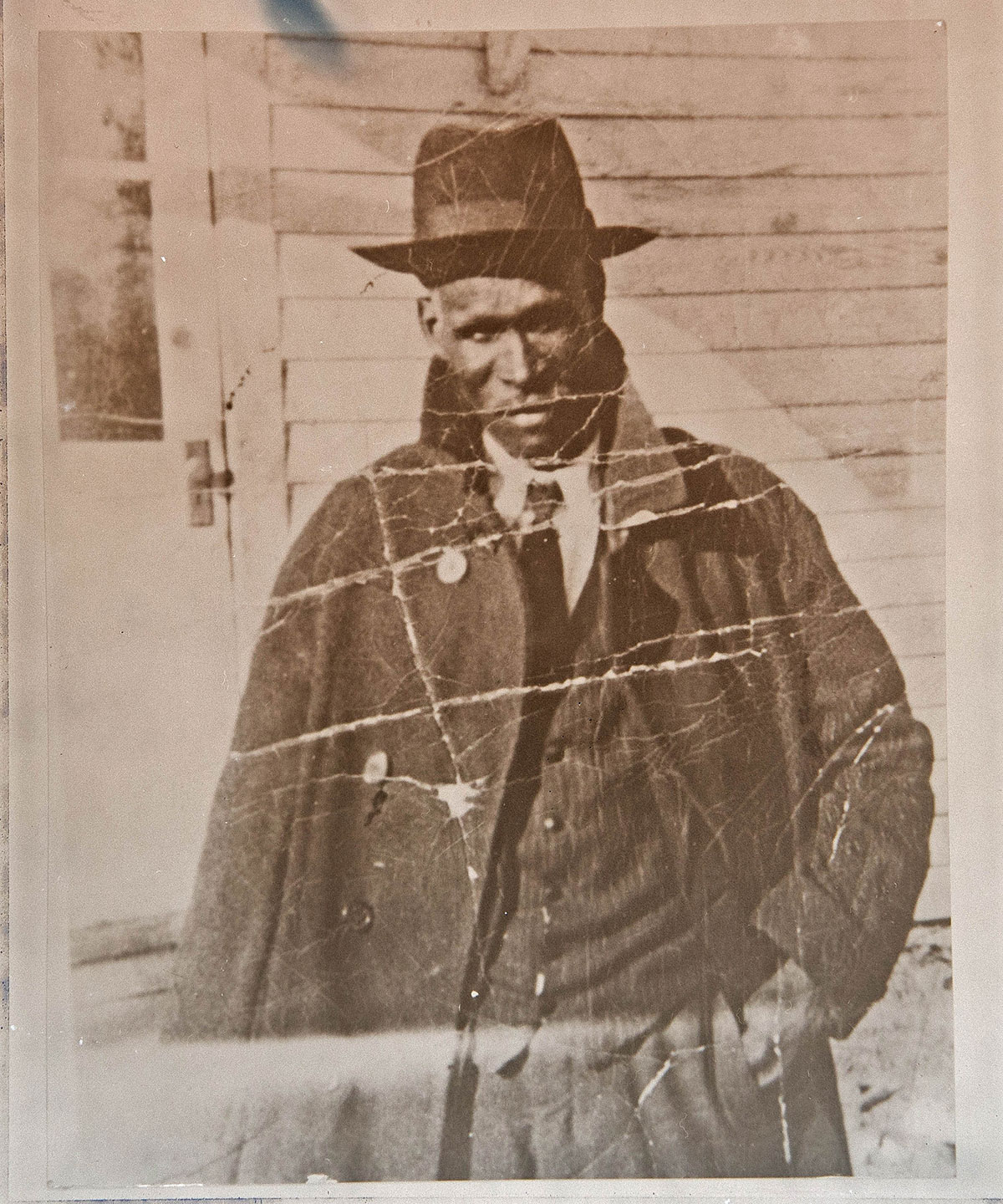

Over the next 20 years, Ella built herself up by learning to read and write. By 1896, she had saved enough money to buy five acres of land in Chesnut Grove, Virginia, and her occupation changes to “farmer” in the 1900 census. Ella’s first land purchase still belongs to Rush’s family.

An undated photo of Ella’s son and Rush’s grandfather, James Neverson Rush. He was born in 1878. (Photo by Dan Addison)

Special Collections and the Scottsville Museum have not been Rush’s only sources on her research journey. She’s turned to local courthouses and the Library of Virginia for official government records, but the collection of the Rives’ letters and ledgers have helped her fill in the gaps between singular names listed on a page and the breadth of the lives lived by her ancestors.

“The Rives family owned over 200 slaves and they had eight or nine plantations, but I still found a ledger with not only my great-great-grandmother, but also my great-great-grandfather across from her. That made me feel like they wanted me to tell our family’s story,” she said. “They didn’t have a voice and I want to give it to them. I want to say, ‘You lived, you were here, and your life mattered.’ It matters to me. Your DNA runs through me and I am who I am because of you.”

Media Contact

Article Information

February 26, 2016

/content/librarian-finds-clues-her-familys-past-hidden-special-collections