It’s an old joke that there are three kinds of people in the world: those who are good at math and those who aren’t.

Tanya Evans, an associate professor in the School of Education and Human Development at the University of Virginia, disagrees. Only a small percentage of people, she said, are inherently bad at math.

“When children or adults struggle with learning to read, the response is, ‘You can do this, and we will teach you how.’ But with math, it’s more of ‘Oh, you’re just not good at math,’ and that’s the end of it. It’s just accepted.”

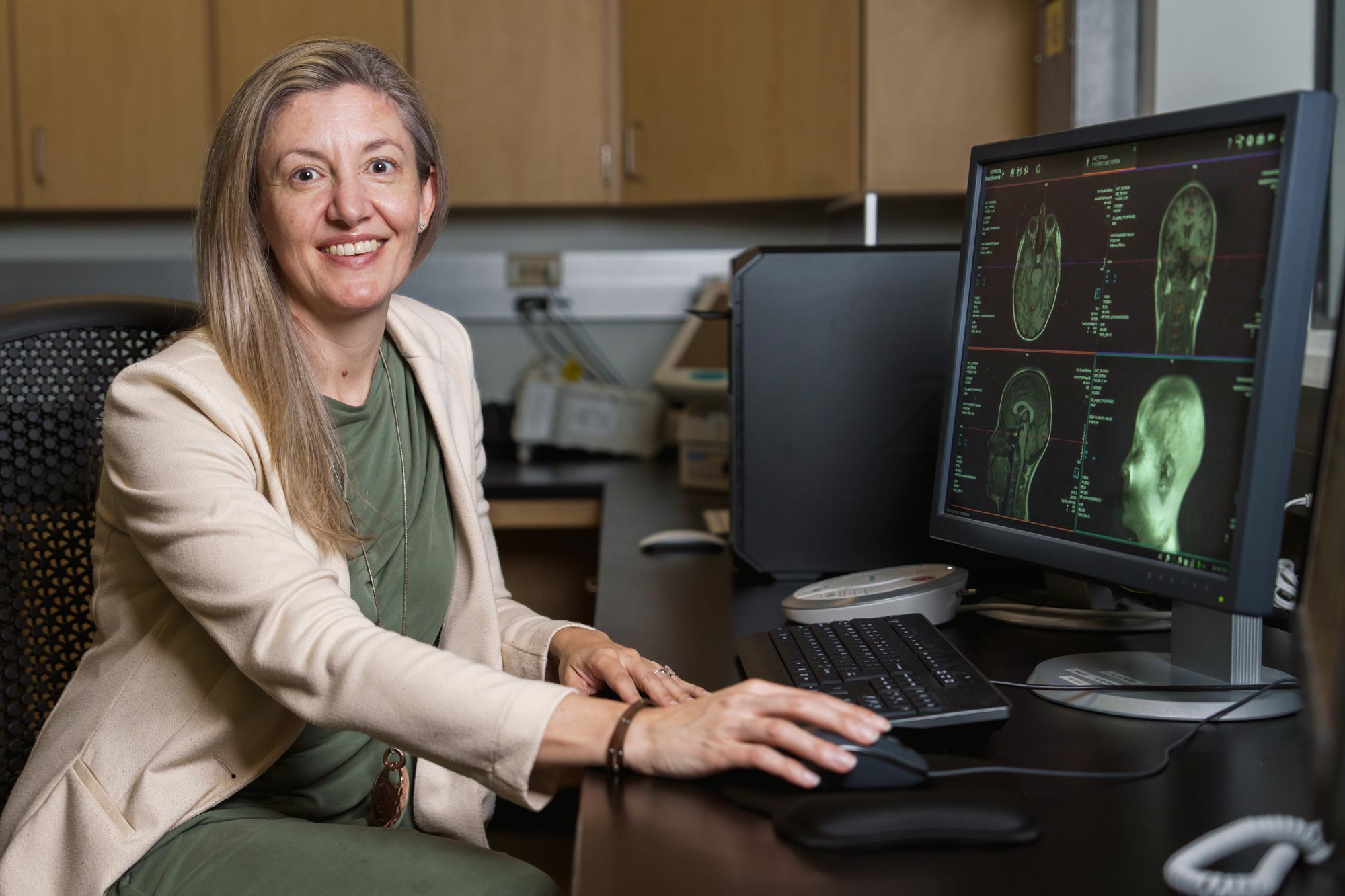

Tanya Evans, an associate professor in the School of Education and Human Development at the University of Virginia, is using technology to better understand how math skills are processed in the brain. (Photo by Lathan Goumas, University Communications)

Evans is a developmental cognitive neuroscientist, which means she studies brain architecture and function, specifically how brain development enables children to acquire the skills needed to be successful in the classroom.

Evans said early education places a heavy emphasis on literacy, with children first learning to read and then reading to learn. Math literacy, however, is not as emphasized.

“You need both skills throughout your life. You need to read, but you also need to make budgets, pay your bills and manage medication schedules,” she said. “There are numbers all around us, and when you’re uncomfortable with them, it makes life more difficult.”

She explains that part of the discomfort with math may be due to math anxiety, passed on to children from math-averse parents.

“There’s some really interesting work showing that parents’ anxiety around doing math and even teachers’ anxiety around doing math can actually influence their children or their students,” Evans said. “Pregnant women see signs in the doctor’s office telling them to read to their children every day and sing songs to them every day, to help with their learning. But no one says to talk about math with your kids every day.”

Curious about how math is learned, Evans has joined with UVA colleague Daniel Lipscomb, Vanderbilt University’s Laurie Cutting, Michael Ullman from Georgetown University and others in studying 109 schoolchildren in second, third and fourth grades over several years to determine foundational skills that support learning math.

The study compared skills that support declarative memory, which is based on facts like where the nation’s capital is located, with those that focus on procedures, such as how to ride a bicycle.