A nagging question she had pondered for years inspired professor Naseemah Mohamed’s latest course: What knowledge could she give students that they would carry with them beyond college? As an assistant professor at the University of Virginia’s Carter G. Woodson Institute for African American and African Studies, Mohamed spends a good deal of time thinking about how to personalize historical events for students.

She realized the answer was to help students better understand themselves. “We come to know ourselves through the web of relationships, past and present, that have made us who we are,” she said.

Mohamed’s own personal genealogical journey inspired her to create her course, Tracing Your Genealogy, offered again in the spring.

Mohamed’s interdisciplinary research examines the relationships among education, media, technology, global politics and violence in the 20th century. (Contributed photo)

“In an increasingly globalized world, the course helps students discover the many stories of their ancestors – of loss, perseverance and triumph – that have culminated in their own being here today,” she said. “I hope it can serve as a blueprint for how institutions might offer students methodologically rigorous training that is also deeply meaningful to them.”

Her undergraduate professor at Harvard College, Henry Louis Gates, who hosts the popular television genealogy series “Finding Your Roots,” set everything in motion. After admitting to Gates she could not trace her ancestry, he gave her a DNA test kit that she took, and then forgot about.

Mohamed and her sister, UVA astronomy professor Shazrene Mohamed, both earned Rhodes Scholarships, which were established by Cecil John Rhodes, the British mining magnate who founded the colony of Rhodesia – now Zimbabwe, where the Mohameds are from, and Zambia. At Oxford, Naseemah sought to confront that colonial history and joined the Rhodes Must Fall movement to decolonize education while studying education and conflict in Zimbabwe.

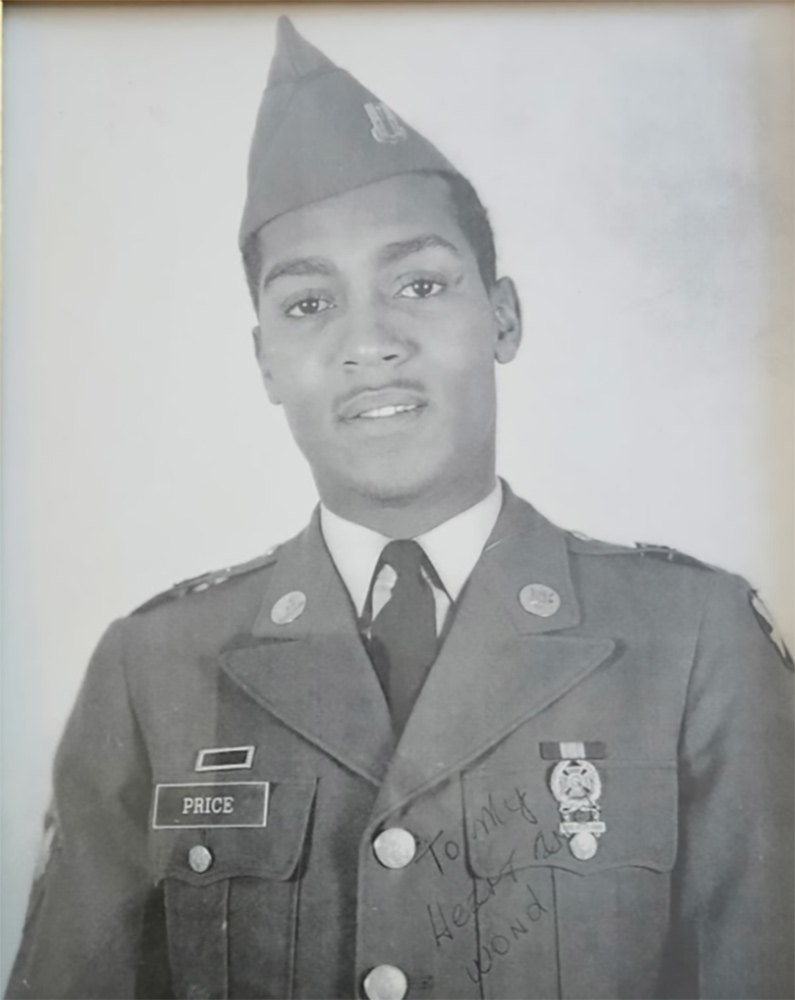

While writing her dissertation, she reopened her 23andMe account and discovered one of her newer relative matches, Shiona Harris, whom she contacted. Harris told her Rhodes had known her twice-great-grandmother, Elizabeth Catherine LeRoux, and had sent her on one of the first trains to Bulawayo, now Zimbabwe’s second-largest city, to be a nanny for his lawyer’s children.

“This discovery of a personal connection with Rhodes transformed my research from an academic exercise into an act of ancestral reckoning,” she said. “It drove home for me that whether we are conscious of it or not, our present histories are tied to the generations who lived before us.”