April 16, 2009 — Inequalities still persist decades after race-based affirmative action policies were adopted to create equal opportunities in employment and education. So maybe it's time to base affirmative action on factors like class and wealth, argued Dalton Conley of New York University and John McWhorter of the Manhattan Institute at a debate co-sponsored by the University of Virginia's Miller Center of Public Affairs.

The April 16 debate, on the future of affirmative action in America, was the third event of "Priorities for a New President," the 2009 season of the National Discussion and Debate Series.

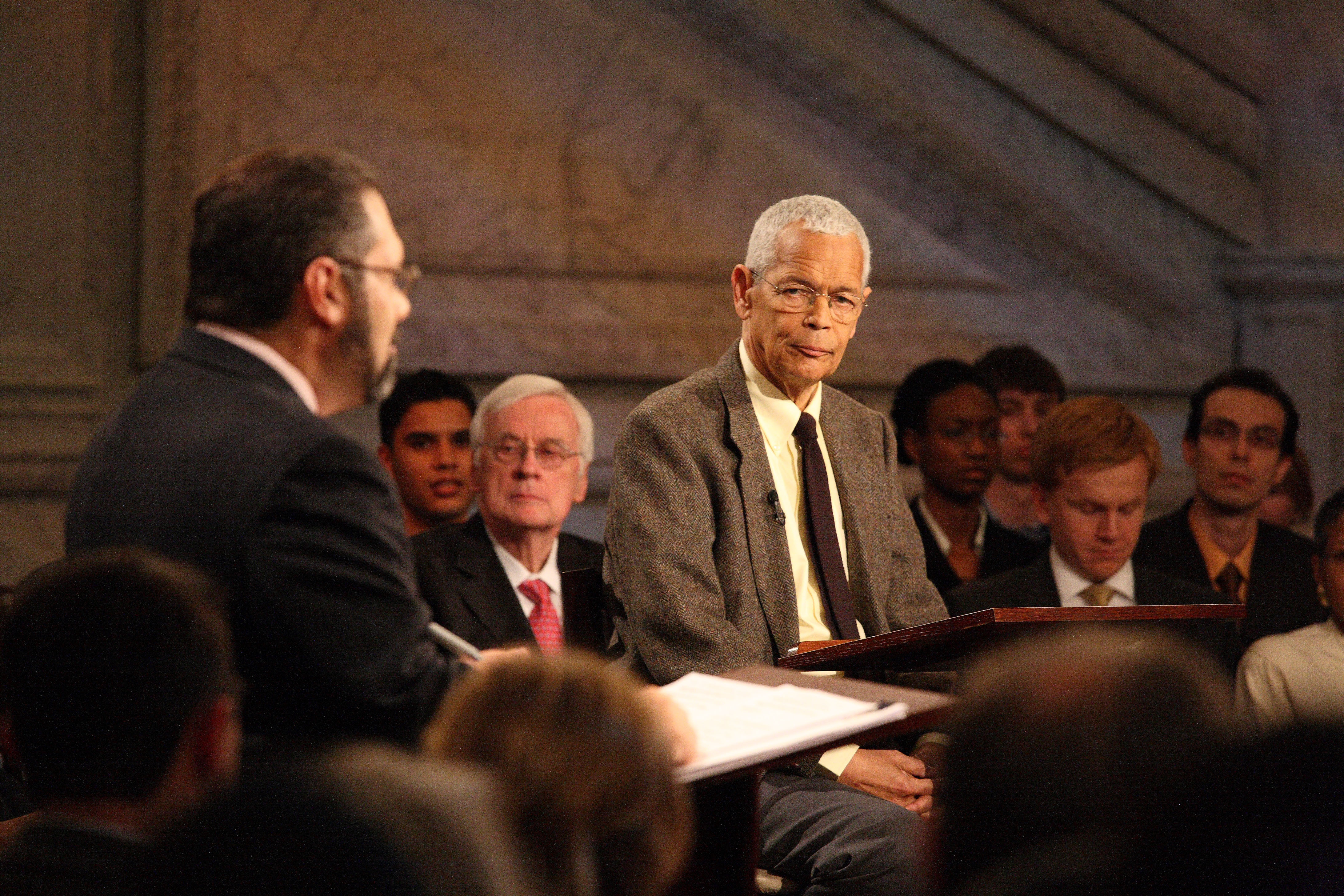

Conley and McWhorter faced off against Julian Bond, chairman of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and a professor of history at U.Va., and Lee C. Bollinger, president of Columbia University, on the resolution: "Affirmative action should focus on class and wealth rather than race and ethnicity."

The debate, moderated by Ray Suarez, senior correspondent for PBS' "The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer," took place in front of a live audience at the Library of Congress in Washington.

Conley stated in his opening remarks that wealth and class impact educational and economic outcomes more than race and ethnicity do, and that racial inequality is connected to class disparities.

"So if race now matters indirectly through its association with class, why do we continue to use it as a factor in admissions?" he asked. A race-blind, class-conscious approach, he contended, would decrease the stigma associated with race-based decisions, while ensuring that those who deserve a chance are more likely to receive it.

"Affirmative action was intended to be a remedy for slavery, for segregation, for racial discrimination – reparations for wrongs of the past," Bond argued. "To substitute class for immutable characteristics of race is to make a mockery of the Civil Rights Movement that gave birth to affirmative action."

The election of an African-American president, albeit historic, does not mean that discrimination suddenly does not exist in America, he said – and because race and wealth are different categories, he argued, race-based affirmative action is still necessary. "Nobody beat Rodney King because he was poor," he said.

McWhorter, a best-selling author and columnist for The New Republic who teaches at Columbia, said that lower standards resulting from race-based affirmative action in college admissions are great cause for concern.

"I think that it would be disingenuous to pretend that there's no such thing as the kind of affirmative action that involves lowering standards," he said. "If you set the bar low, then overall that's the kind of performance that you're going to get."

But racial diversity in the academic environment is too important to be addressed through class and wealth, Bollinger argued.

"Countless things are considered in the course of admitting students," he said. "Geographic diversity, athletic diversity, international diversity, students who have many different kinds of backgrounds and experiences – [it's] very important to get them together in a class. It's also extremely important to realize that you will not get racial diversity if you rely just on class and wealth."

"With wealth, given how unequally distributed it is by race, you get your cake and eat it too," Conley countered, "because you will get a diverse racial composition of a campus if you use wealth and not income as a basis of a class policy."

McWhorter argued that the purpose of affirmative action – to address the effects of Jim Crow and the open social bigotry of the time – made sense for a generation. But open discrimination is no longer the norm, and the time for race-based policies has passed.

"Affirmative action is like chemotherapy," he said. "It creates all kinds of problems in society… and it does create a stigma. And it has been shown to put a cramp on the incentive or even the knowledge of exactly what one actually needs to do in order to hit the highest bar because you don't have to."

The debaters also discussed the use of race-based affirmative action in publicly vs. privately funded institutions, the use of the term "diversity," the perceptions of education within the black community, the immutability of race versus the mutability of wealth, and the level of stigmatization toward other affirmative action beneficiaries, including university legacy admissions.

During closing remarks, Bond argued that affirmative action policies must address race to successfully counteract racism. "To substitute class for race and affirmative action is to deny history, deny reality and deny justice," he said.

McWhorter concluded by looking ahead to his daughter's future prospects as she applies to college. "If the idea is that the administrators are beaming because my daughter is going to make the campus more diverse, if they are beaming because by admitting my daughter they're showing that racism is not dead, … I will feel that my daughter is being condescended to."

The National Discussion and Debate Series is produced for broadcast by MacNeil/Lehrer Productions. "The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer" airs highlights from each debate, and PBS stations around the country will air them throughout the spring. Check local listings for details.

More information, including debate video and a transcript, is online here.

This season's final debate, on America's energy future, will take place May 14 at U.Va.'s Newcomb Hall.

The April 16 debate, on the future of affirmative action in America, was the third event of "Priorities for a New President," the 2009 season of the National Discussion and Debate Series.

Conley and McWhorter faced off against Julian Bond, chairman of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and a professor of history at U.Va., and Lee C. Bollinger, president of Columbia University, on the resolution: "Affirmative action should focus on class and wealth rather than race and ethnicity."

The debate, moderated by Ray Suarez, senior correspondent for PBS' "The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer," took place in front of a live audience at the Library of Congress in Washington.

Conley stated in his opening remarks that wealth and class impact educational and economic outcomes more than race and ethnicity do, and that racial inequality is connected to class disparities.

"So if race now matters indirectly through its association with class, why do we continue to use it as a factor in admissions?" he asked. A race-blind, class-conscious approach, he contended, would decrease the stigma associated with race-based decisions, while ensuring that those who deserve a chance are more likely to receive it.

"Affirmative action was intended to be a remedy for slavery, for segregation, for racial discrimination – reparations for wrongs of the past," Bond argued. "To substitute class for immutable characteristics of race is to make a mockery of the Civil Rights Movement that gave birth to affirmative action."

The election of an African-American president, albeit historic, does not mean that discrimination suddenly does not exist in America, he said – and because race and wealth are different categories, he argued, race-based affirmative action is still necessary. "Nobody beat Rodney King because he was poor," he said.

McWhorter, a best-selling author and columnist for The New Republic who teaches at Columbia, said that lower standards resulting from race-based affirmative action in college admissions are great cause for concern.

"I think that it would be disingenuous to pretend that there's no such thing as the kind of affirmative action that involves lowering standards," he said. "If you set the bar low, then overall that's the kind of performance that you're going to get."

But racial diversity in the academic environment is too important to be addressed through class and wealth, Bollinger argued.

"Countless things are considered in the course of admitting students," he said. "Geographic diversity, athletic diversity, international diversity, students who have many different kinds of backgrounds and experiences – [it's] very important to get them together in a class. It's also extremely important to realize that you will not get racial diversity if you rely just on class and wealth."

"With wealth, given how unequally distributed it is by race, you get your cake and eat it too," Conley countered, "because you will get a diverse racial composition of a campus if you use wealth and not income as a basis of a class policy."

McWhorter argued that the purpose of affirmative action – to address the effects of Jim Crow and the open social bigotry of the time – made sense for a generation. But open discrimination is no longer the norm, and the time for race-based policies has passed.

"Affirmative action is like chemotherapy," he said. "It creates all kinds of problems in society… and it does create a stigma. And it has been shown to put a cramp on the incentive or even the knowledge of exactly what one actually needs to do in order to hit the highest bar because you don't have to."

The debaters also discussed the use of race-based affirmative action in publicly vs. privately funded institutions, the use of the term "diversity," the perceptions of education within the black community, the immutability of race versus the mutability of wealth, and the level of stigmatization toward other affirmative action beneficiaries, including university legacy admissions.

During closing remarks, Bond argued that affirmative action policies must address race to successfully counteract racism. "To substitute class for race and affirmative action is to deny history, deny reality and deny justice," he said.

McWhorter concluded by looking ahead to his daughter's future prospects as she applies to college. "If the idea is that the administrators are beaming because my daughter is going to make the campus more diverse, if they are beaming because by admitting my daughter they're showing that racism is not dead, … I will feel that my daughter is being condescended to."

The National Discussion and Debate Series is produced for broadcast by MacNeil/Lehrer Productions. "The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer" airs highlights from each debate, and PBS stations around the country will air them throughout the spring. Check local listings for details.

More information, including debate video and a transcript, is online here.

This season's final debate, on America's energy future, will take place May 14 at U.Va.'s Newcomb Hall.

— By Kim Curtis

Media Contact

Article Information

April 16, 2009

/content/miller-center-debate-should-inequality-be-addressed-race-or-class-based-affirmative-action