As a girl, Dukes was captivated by Ayn Rand, a popular philosopher of the time and author of “The Fountainhead” and “Atlas Shrugged.” Rand called her philosophy “objectivism” and defined it as “the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive achievement as his noblest activity, and reason as his only absolute.” Rand advocated for laissez-faire capitalism, a system in which transactions are private and free from government interference.

With Rand’s perspectives in mind, Dukes headed to the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, to study business and finance. A talented student, she was placed in an honors program that required study in sciences. That led her to take a course in high-energy physics, forever changing the trajectory of her life.

“It was so exciting, so interesting,” she said. “I think just the logic behind it, and the thought process behind how to understand how the universe was created, and what things were made of, really influenced me deeply.”

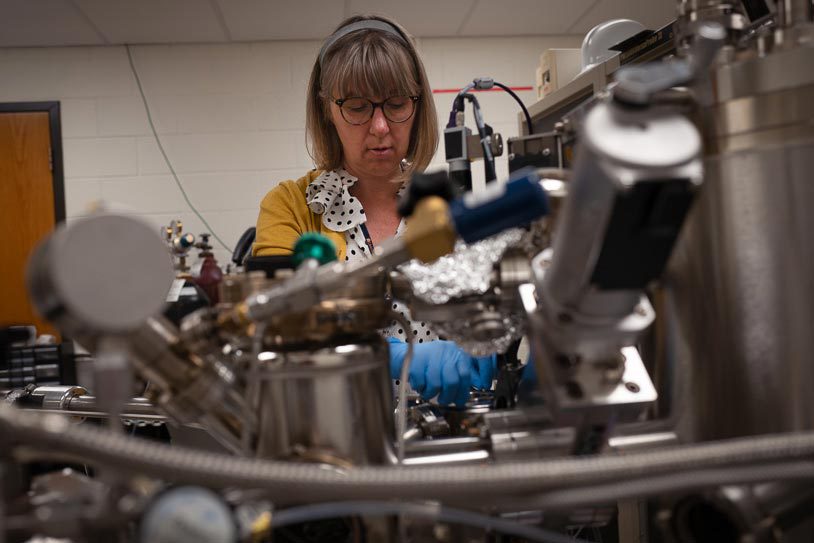

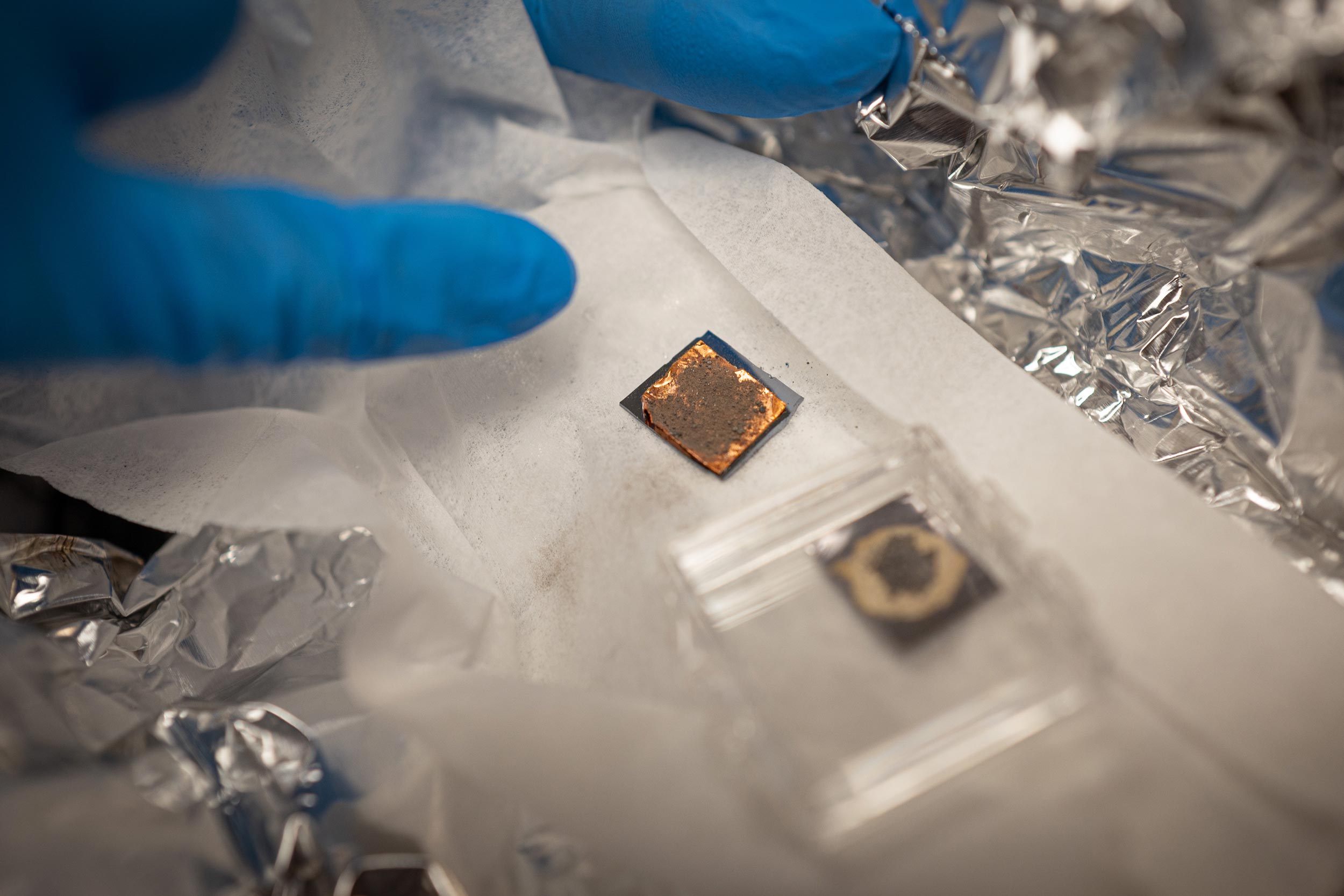

As a new physics major, Dukes initially studied elementary particle physics. But after arriving at UVA for her master’s degree, she began working with a surface physicist in engineering physics with an interest in planetary science, studying the interaction of radiation with surfaces. Their work prompted a call from a senior scientist at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, Roy Christoffersen, who wanted their help in understanding more about how the moon’s surface has been affected by the solar wind and meteoritic collisions. In particular, NASA wanted to know more about how solar ions – like protons and helium – damage the surface of lunar grains, changing their physical structure and chemistry.

That call launched her on a mission of discovery about the lunar surface and a relationship with NASA that continues to this day.

Ballet Dancing on the Moon

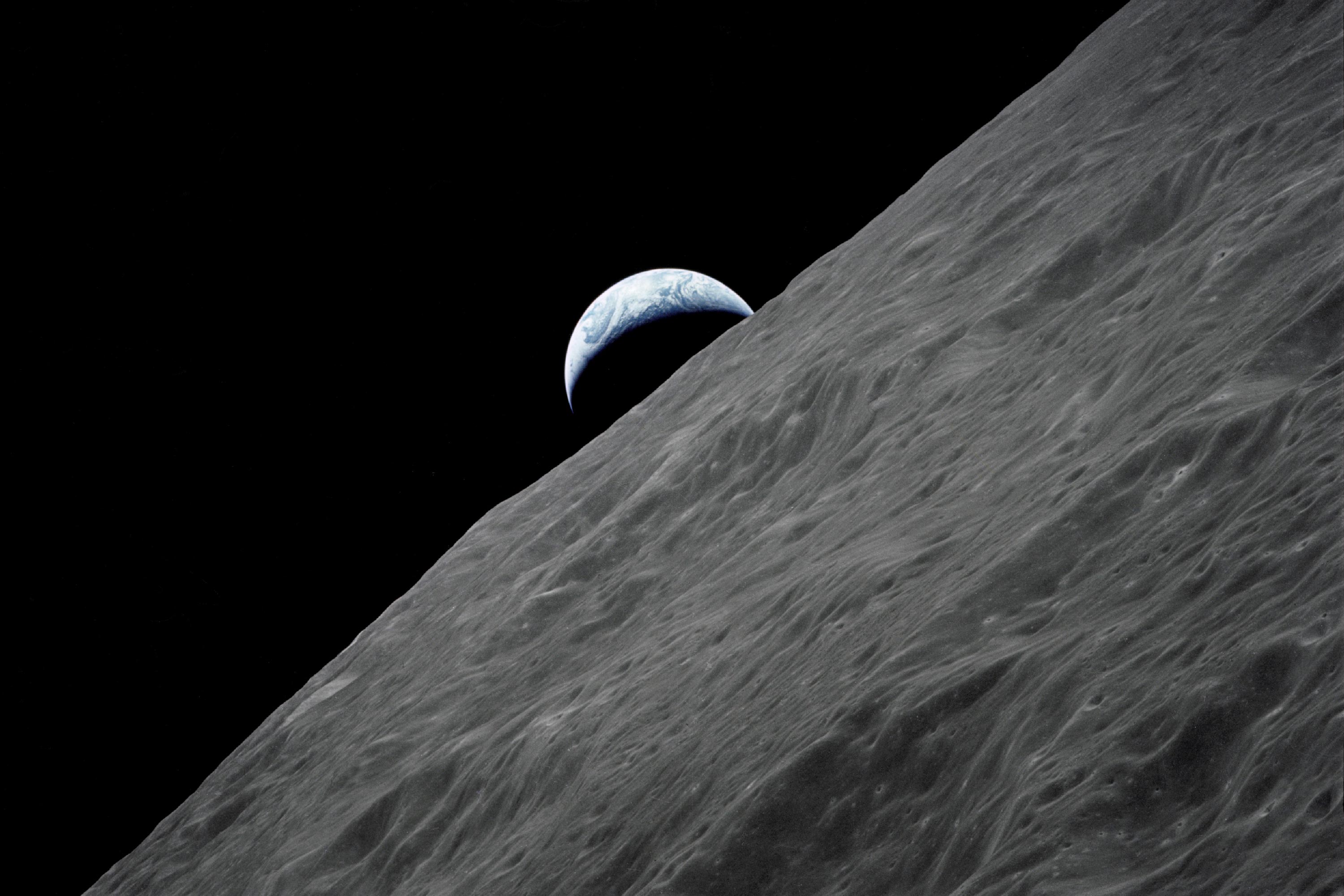

The Apollo 17 lunar module plopped down with two crew members in the moon’s Taurus-Littrow Valley on the southeastern edge of the Sea of Serenity on Dec. 11, 1972. The site was chosen because of its proximity to hills and lowland areas as well as potential volcanic vents, impact craters and perhaps even a mountain slide.

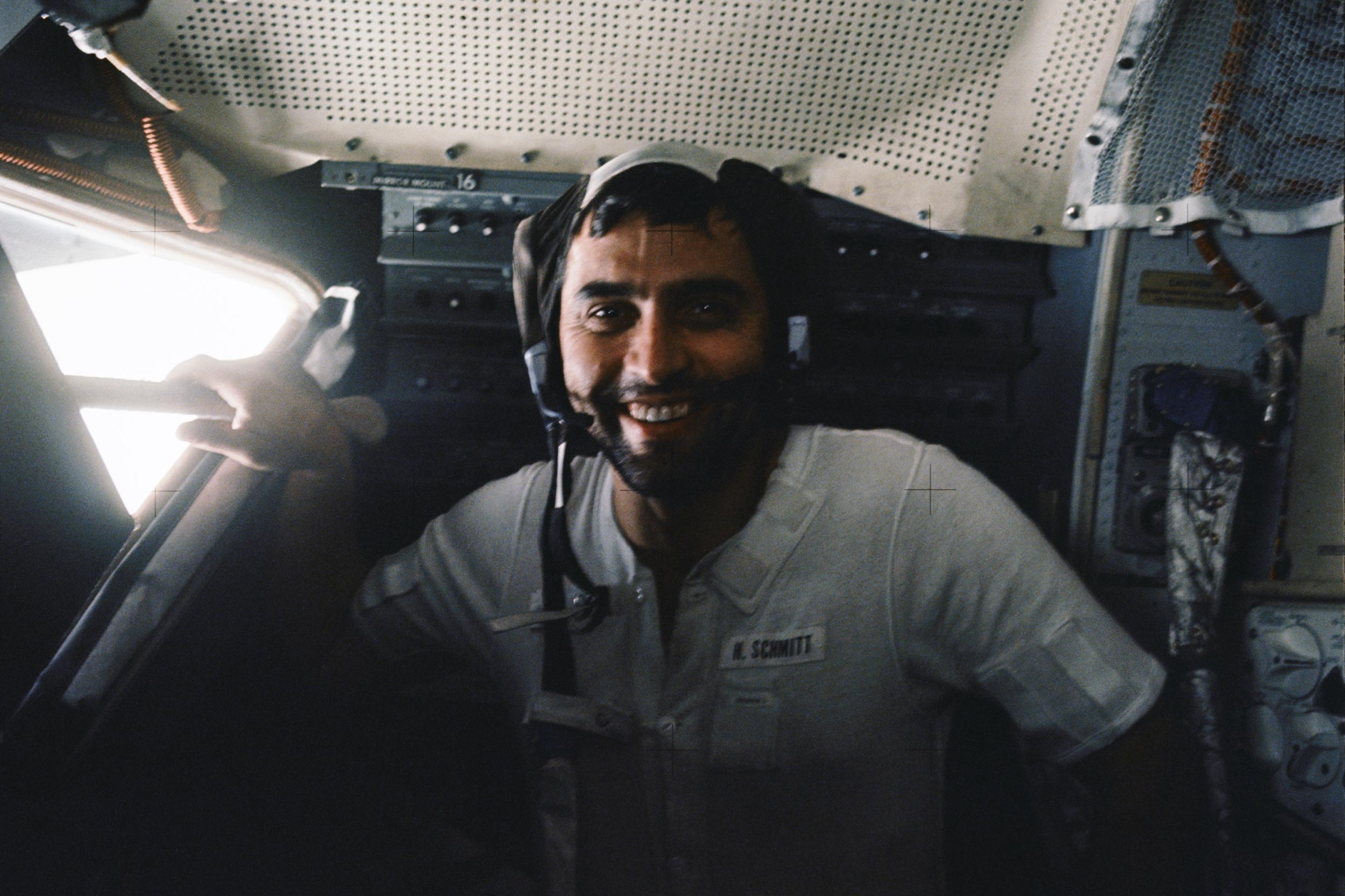

On the second day of their three-day mission, commander Eugene “Gene” Cernan and geologist Harrison “Jack” Schmitt, the first lunar astronaut-scientist, woke with NASA blaring “Ride of the Valkyries” by Richard Wagner, a throwback to the astronauts’ days as undergrads at the California Institute of Technology, where it’s tradition to play the opera at top volume on the mornings of final exams.

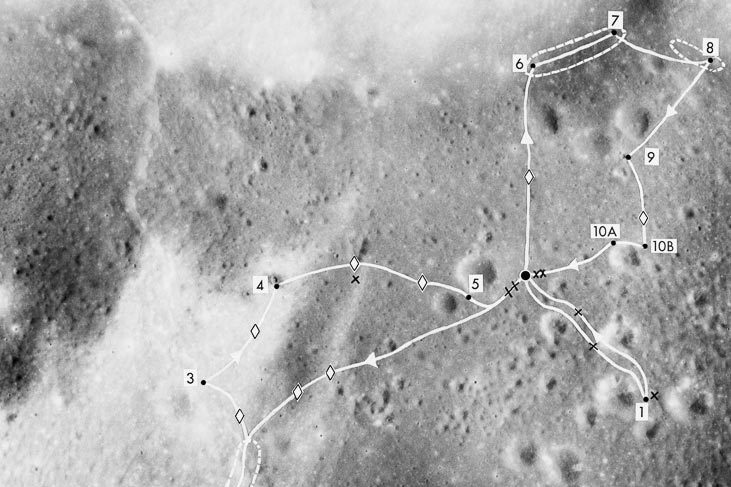

NASA knew this might be the last human mission to the moon, and there was a lot on the agenda for the day. More than 20 kilometers of traversing areas to the south and west of the landing site lay ahead, with four major sampling sites and eight minor ones. The hope was to collect samples that might lead scientists and researchers to learn more about the moon’s relationship with Earth and perhaps answer questions about the origins of the universe and life itself.