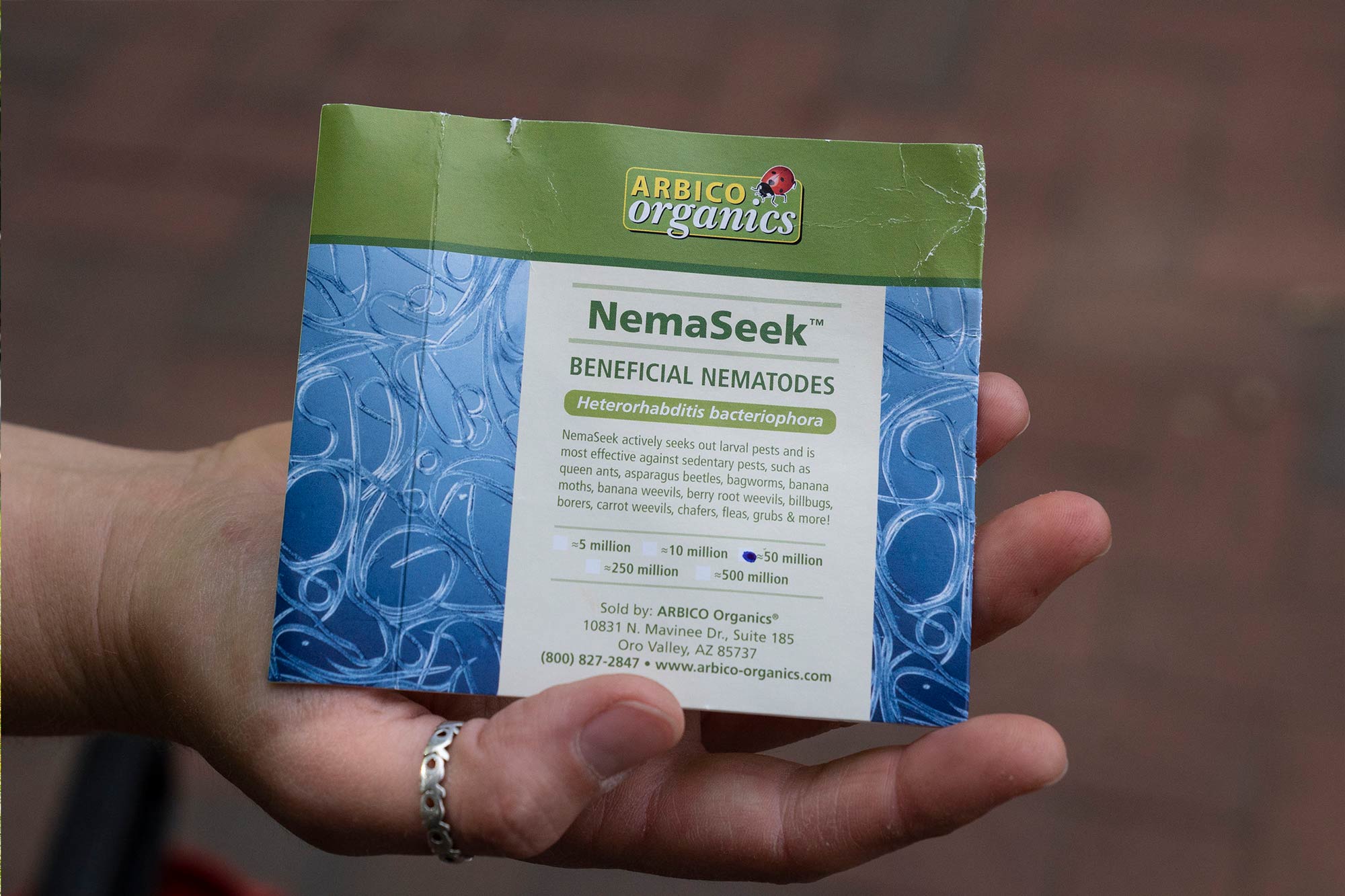

Em Ford walked carefully around a recently sodded patch of lawn in front of the University of Virginia’s Alderman Library, spraying a watery mix of nematodes, a beneficial roundworm, in a grid pattern to destroy grubs that would damage the new turf.

It’s a case of nature helping to balance nature.

“The grubs in questions are those of the invasive Japanese beetle, Popillia japonica,” said Ford, the University’s landscape plant health specialist. “This is the time when beetles have mated and laid their eggs in the soil for their grubs to develop through late summer, fall, winter and next spring, thus emerging as adults around June.”

The soil-dwelling grubs feed on the roots of plants; in this case, the roots of the turf grass. They ultimately kill it from beneath the surface.

.jpg)