The tour app brings together information about people who worked at UVA and significant places – some that are still standing, some that were hidden and then found accidentally, and some that have left little trace, but emerge from documents and drawings.

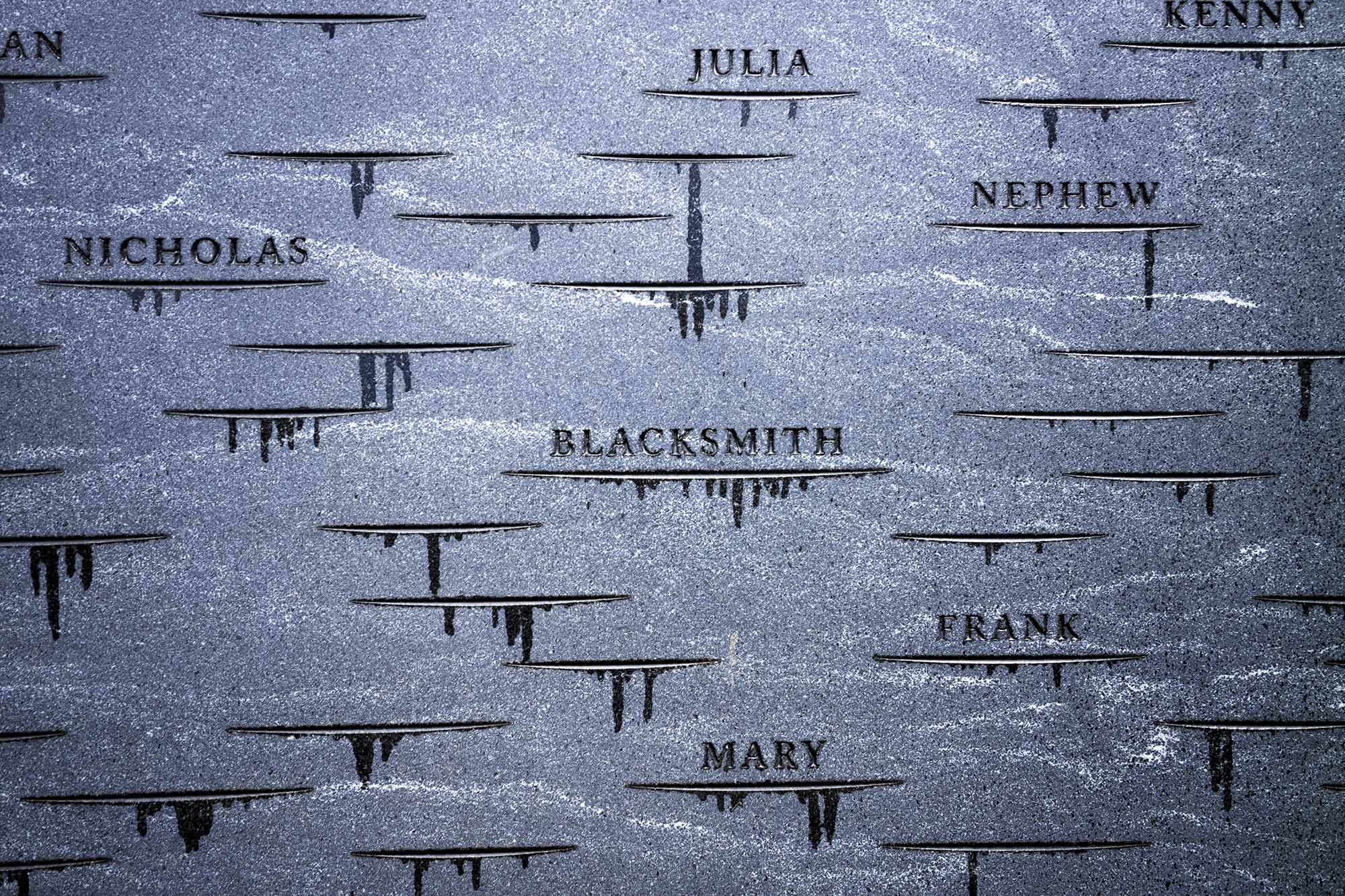

For instance, Robert Battles was a free man of color who hauled more than 176,000 bricks used in the construction of the Rotunda. Enslaved laborers, including young boys, made those bricks. Of the hundreds of enslaved workers who helped build the University, many were skilled craftsmen in stonecutting, carpentry and blacksmithing. According to the walking tour, Battles owned a nearby 26-acre farm, which John Hartwell Cocke pressured him to sell. “After years of hard negotiation,” he finally sold it in 1825 for $2,000 (which would be the equivalent of about $50,000 today).

Enslaved and free Black people, including children, supported the operation of daily life, working in the dining rooms of hotels in the Academical Village, doing laundry and sewing for faculty and students.

Only a few outbuildings used by the enslaved workers survive, but app users can see photos as well as plans for buildings that are gone or were never built. One part of Hotel E, Mrs. Gray’s kitchen, was finished in 1830 and probably torn down between 1915 and 1920, but app users can see an architectural drawing with notes and a photo of where it stood. Records show that the kitchen structure was expanded for the lodging of a dozen or more “servants,” as enslaved laborers were euphemistically called. There’s also information from faculty meeting minutes about Mrs. Gray complaining that a student struck a young servant named William, who was then removed from attending to students.