In a 1948 issue of Life magazine, a photo essay entitled “Harlem Gang Leader” introduced Gordon Parks to the world.

Although Parks had been a professional photographer for nearly a decade, his name was virtually unknown, something he shared with the vast majority of professional photographers at that time. But his byline in Life – by far the most widely read news and photo magazine in America – changed all that.

Opening Friday at The Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia and running through Dec. 21, “Gordon Parks: The Making of an Argument” explores the untold story behind the photo essay that introduced one of the 20th century’s most important African-American photographers, filmmakers and writers to the American public.

The exhibition was curated and organized by Russell Lord, Freeman Family Curator of Photographs at the New Orleans Museum of Art. The items in the exhibition have been made available through the generosity of The Gordon Parks Foundation.

Lord will give a pre-opening lecture, “The Making of an Argument: Gordon Parks and the Harlem Gang Leader Essay,” on Thursday at 6 p.m. in Campbell Hall, room 153, at the School of Architecture. The lecture is free and open to the public.

The exhibition was also organized specifically for The Fralin by John Mason, associate professor and associate chair of U.Va.’s Corcoran Department of History.

“Working on the exhibition has been a real challenge,” Mason said. “Parks was such a complex character. His photographs raise such difficult questions about the representation of African-Americans in popular culture and about the objectivity of reporting in the mass media that, initially, my ideas seemed to change every minute.”

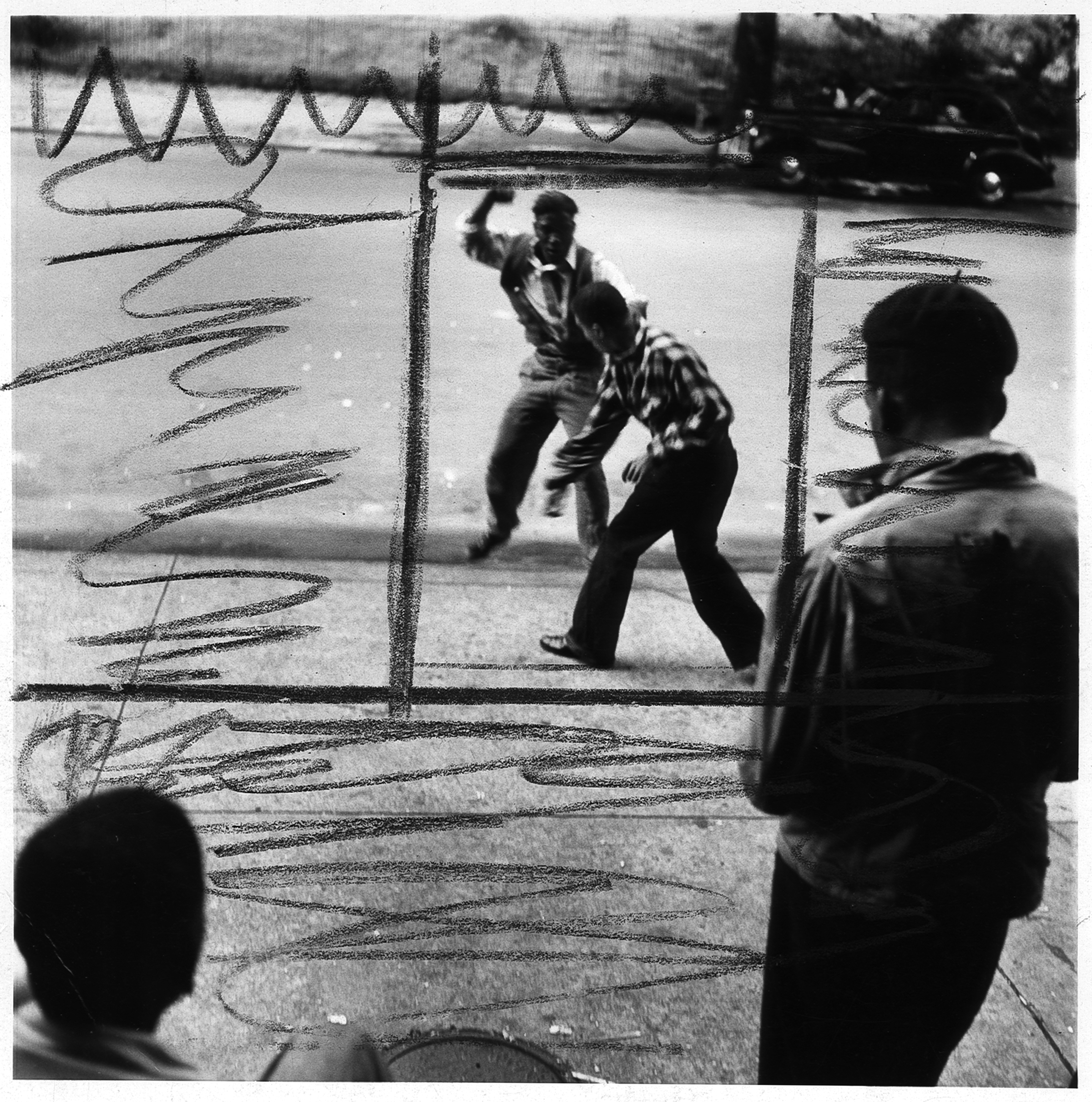

Parks’ photographs and the magazine’s text – which relied heavily on his reporting – led readers to the world of Red Jackson, a 17-year-old Harlem gang leader. Parks spent a month with Jackson and his gang, the Midtowners, while working on the story. Gaining the young men’s trust, he was able to take photographs that revealed a fly-on-the-wall intimacy and the dramatic urgency of film noir.

The response to the Life spread was overwhelmingly positive. Wilson Hicks, the magazine’s photo editor, gave Parks a job, making him the first – and, for the next 20 years, the only – African-American photographer on the staff of a major American magazine or newspaper.

Despite its success, the essay troubled Parks. While Jackson’s world did contain more than its share of violence and fear, the emphasis that the magazine’s editors placed on those aspects created a one-sided story. Parks knew, however, that without this edginess, Life might never have published the essay.

Parks’ frustration was rooted in the tension between his hopes for the essay and the final product. His aim was to produce a photo essay that would illustrate the conditions that fostered delinquency – and to encourage government and social service agencies to intervene. Life magazine offered him the platform, but it came with a price: He had to surrender control to the magazine’s editors.

The Fralin exhibition brings together scores of the Parks Foundation’s published and unpublished photographs, contact sheets, proof prints and original copies of Life to examine the way in which editorial decisions altered Parks’ original vision. The result is a close study of the way Parks’ work was conceived, constructed and received.

“Looking through Parks’ contact sheets and prints in the archive of the Gordon Parks Foundation was a revelation,” Mason said. “The first thing I noticed is that the photographs that were published – in Life for ‘Harlem Gang Leader’ and in subsequent books – are only the tip of a very large iceberg.

“Parks made hundreds of photographs for every story that he worked on – and many of his unseen images are simply brilliant. The best of his many photo essays for Life, all of which touched on issues related to poverty and social justice, are among the strongest that the magazine ever published.”

During Parks’ first 18 months at the magazine, he worked on 52 stories about subjects as diverse as crime, fashion, sports and politics. Beginning in the early 1960s, he also began to write the text for many of his essays.

“Despite his versatility, his claim to greatness as a photographer and journalist will always rest on the photo essays that addressed justice and inequality,” Mason said. “The power of his photographs and the eloquence of his words made him one of the most important interpreters of the black experience in mid-20th-century America.”

Parks spent several weeks with the Harlem gang members, producing more than 1,000 negatives; the editors at Life chose only 21 pictures for reproduction in a graphic and adventurous layout in the magazine. This editorial process begs the question: What was left out and why?

Lord will address these questions in Thursday’s pre-opening lecture. He previously has held positions at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Yale University Art Gallery, and has written widely on the history of photography. Much of his research focuses on the relationships between photography and other visual media.

In addition, Mason will give a special tour of the exhibit Saturday from 2 to 3 p.m. and a lunchtime talk in the museum on Nov. 11 from noon to 1 p.m.

Mason has written extensively on 19th-century South African history, the history of slavery and the history of photography. He is currently working on “Picturing Africa in the American Century,” a book about the ways in which American magazines, especially Life, represented Africa from the end of World War II until the 1970s.

“I’m especially pleased to be studying and writing about Parks at this particular moment,” Mason said. “While Parks has been recognized as a fine photographer for many decades, curators and historians are only now appreciating the depth of his achievement.”

The Fralin Museum of Art’s programming is made possible by the support of The Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation.

The exhibition is also made possible by the Buckner W. Clay Endowment for the Humanities, Arts$, the Office of the Vice President and Chief Officer for Diversity and Equity, the Corcoran Department of History, the Office of the Dean of the College of Arts & Sciences, the Vice Provost for Academic Affairs, the Carter G. Woodson Institute for African-American and African Studies, the American Studies Program at the University of Virginia, the Woodrow Wilson Department of Politics, WTJU 91.1 FM, albemarle magazine, and Ivy Publications LLC’s Charlottesville Welcome Book.

Media Contact

Article Information

September 17, 2014

/content/new-exhibit-goes-behind-scenes-re-examine-landmark-1948-photo-essay