University of Virginia School of Medicine researchers have linked sensitivity to an allergen in red meat – a sensitivity spread by tick bites – with a buildup of fatty plaque in the arteries of the heart. This buildup may increase the risk of heart attacks and stroke.

The bite of the lone star tick can cause people to develop an allergic reaction to red meat. However, many people who do not exhibit symptoms of the allergy are still sensitive to the allergen found in meat. UVA’s new study linked sensitivity to the allergen with the increased plaque buildup, as measured by a blood test.

The researchers emphasize that their findings are preliminary, but say further research is warranted.

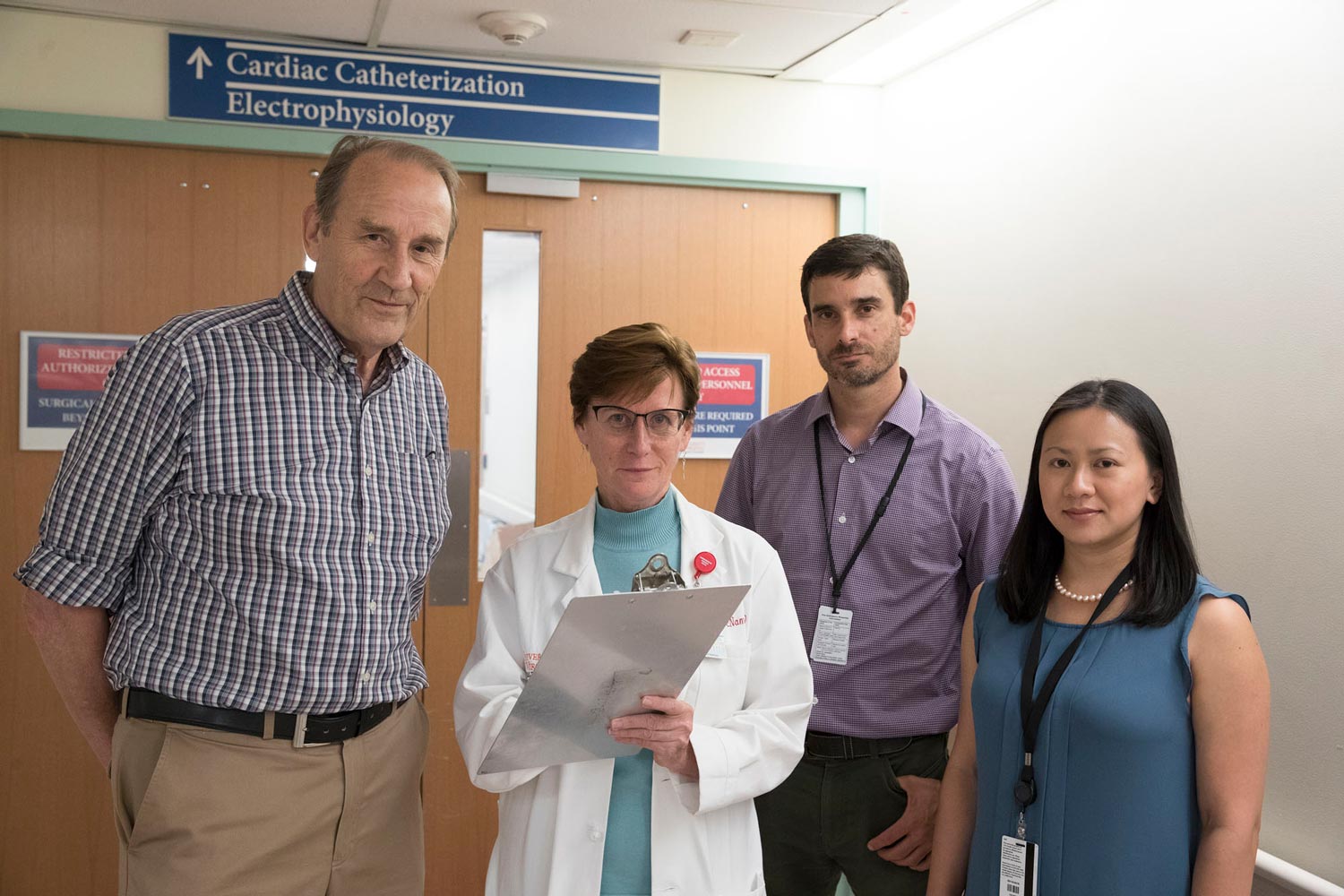

The research team drew from both allergists and cardiologists, and included, from left, Dr. Thomas Platts-Mills, Dr. Coleen McNamara, Dr. Jeff Wilson and Anh Nguyen. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

“This novel finding from a small group of subjects examined at the University of Virginia raises the intriguing possibility that asymptomatic allergy to red meat may be an under-recognized factor in heart disease,” said study leader Dr. Coleen McNamara of UVA’s Robert M. Berne Cardiovascular Research Center and UVA’s Division of Cardiovascular Medicine. “These preliminary findings underscore the need for further clinical studies in larger populations from diverse geographic regions.”

Allergens and Clogged Arteries

Looking at 118 patients, the researchers determined that those sensitive to the meat allergen had 30 percent more plaque accumulation inside their arteries than those without the sensitivity. Further, a higher percentage of the plaques had features characteristic of unstable plaques that are more likely to cause heart attacks.

With the meat allergy, people become sensitized to alpha-gal, a type of sugar found in red meat. People with the symptomatic form of the allergy can develop hives, stomach upset, have trouble breathing or exhibit other symptoms three to eight hours after consuming meat from mammals. (Poultry and fish do not trigger a reaction.)

[What’s it like to develop a meat allergy?]

Other people can be sensitive to alpha-gal and not develop symptoms. In fact, far more people are thought to be in this latter group. For example, up to 20 percent of people in Central Virginia and other parts of the Southeast may be sensitized to alpha-gal, but not show symptoms.

The allergy to alpha-gal was first reported in 2009 by Dr. Thomas Platts-Mills, who heads UVA’s Division of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, and his colleague Dr. Scott Commins. Since then, there have been increasing numbers of cases of the meat allergy reported across the U.S., especially as the lone star tick’s territory grows. Previously found predominantly in the Southeast, the tick has now spread west and north, all the way into Canada.

UVA’s new study suggests that doctors could develop a blood test to benefit people sensitive to the allergen. “This work raises the possibility that in the future a blood test could help predict individuals, even those without symptoms of red meat allergy, who might benefit from avoiding red meat. However, at the moment, red meat avoidance is only indicated for those with allergic symptoms,” said researcher Dr. Jeff Wilson of UVA’s allergy division.

Findings Published

The work represents a significant collaboration between allergy and cardiology experts at UVA. The researchers have published their findings in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology, a journal of the American Heart Association. The research team consisted of Wilson, Anh Nguyen, Alexander Schuyler, Commins, Angela Taylor, Platts-Mills and McNamara.

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, grants KO8-AI085190, K23-HL093118, RO1-AI 20565, PO1-HL55798, RO1-HL136098-01 and RO1-HL107490.

Media Contact

Article Information

June 14, 2018

/content/new-uva-study-tentatively-links-ticks-heart-disease