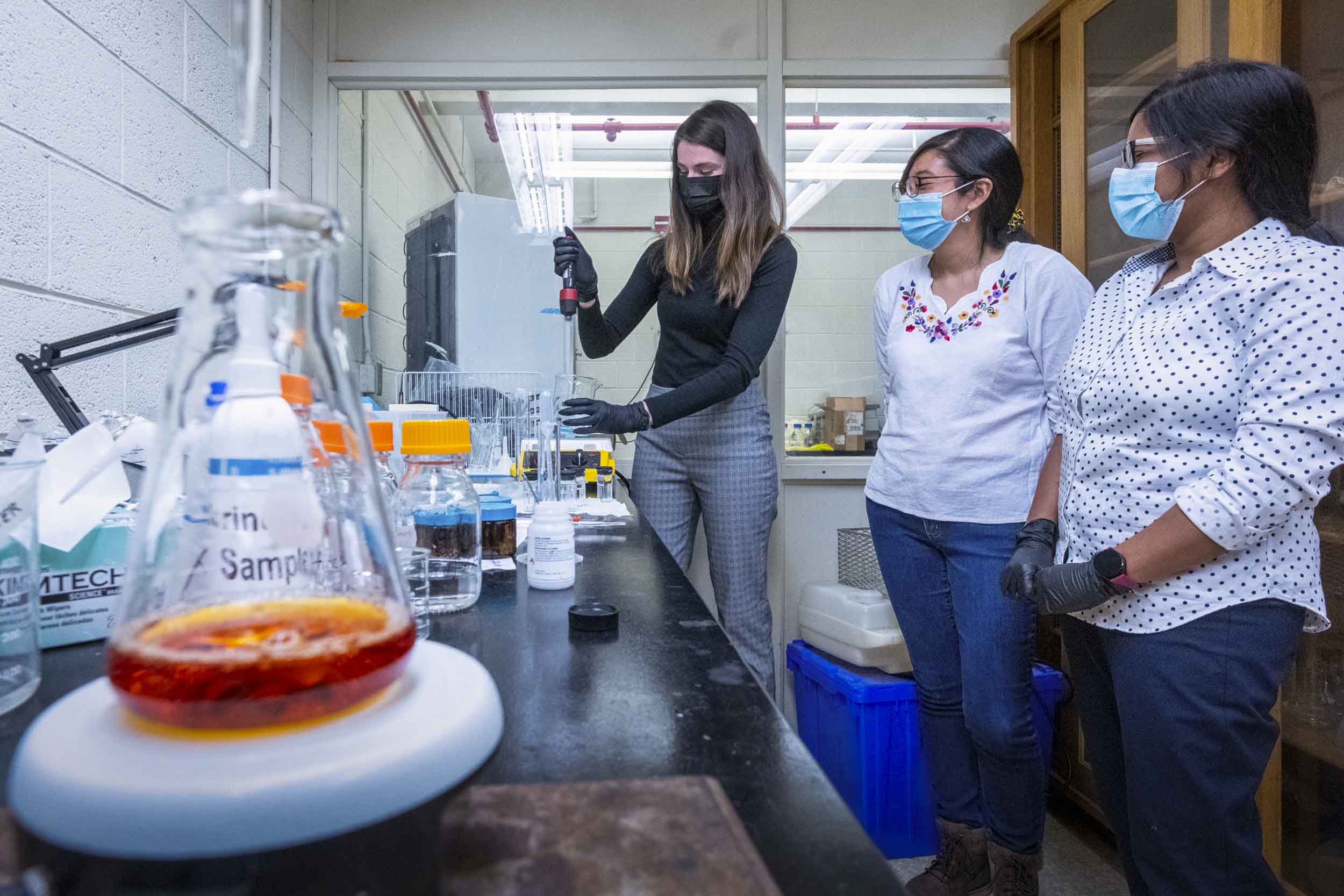

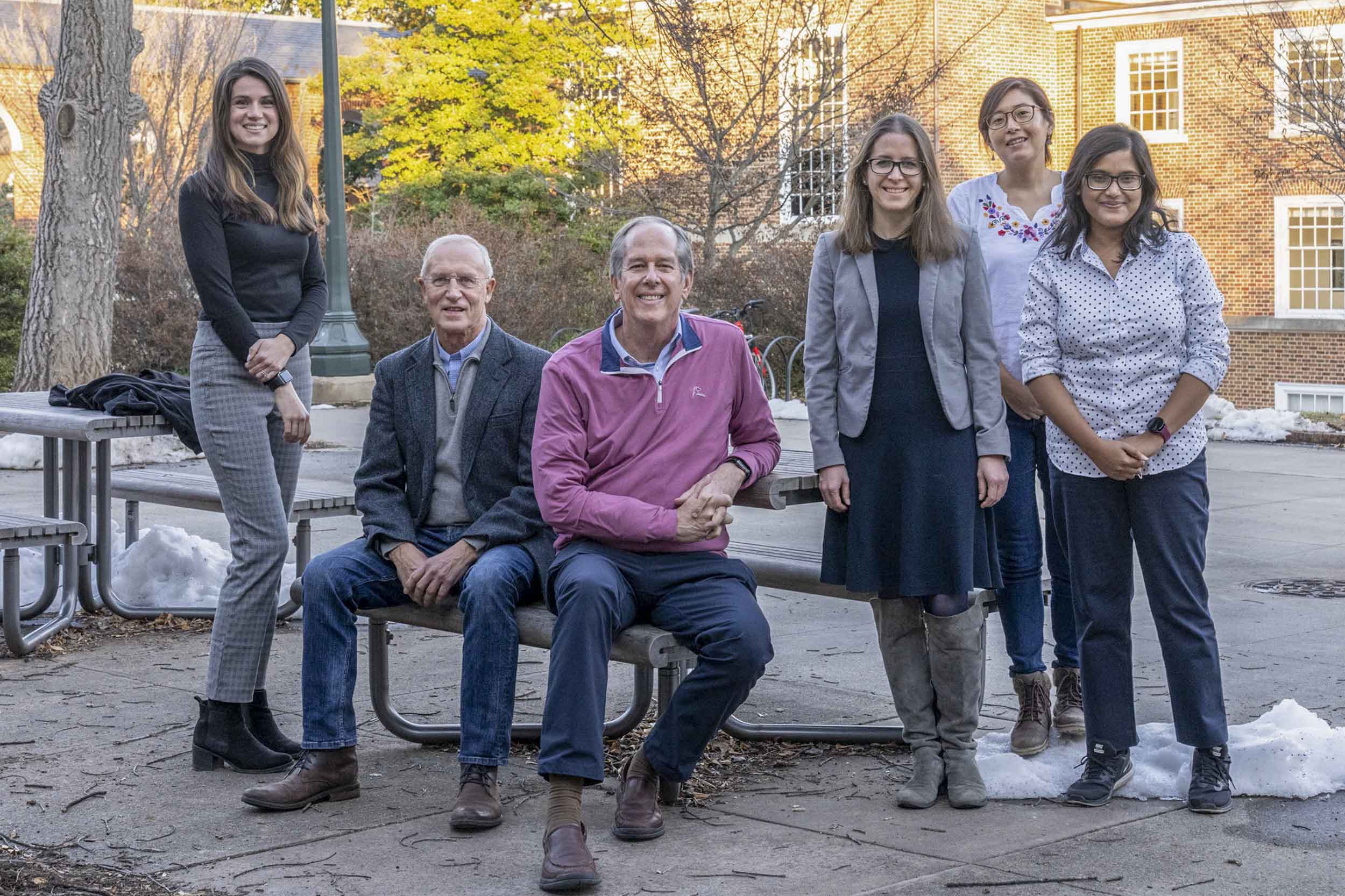

It has been almost a decade since a University of Virginia professor of civil and environmental engineering, James Smith, set out with students to develop a transformational water-disinfecting technology for low-resource communities around the world.

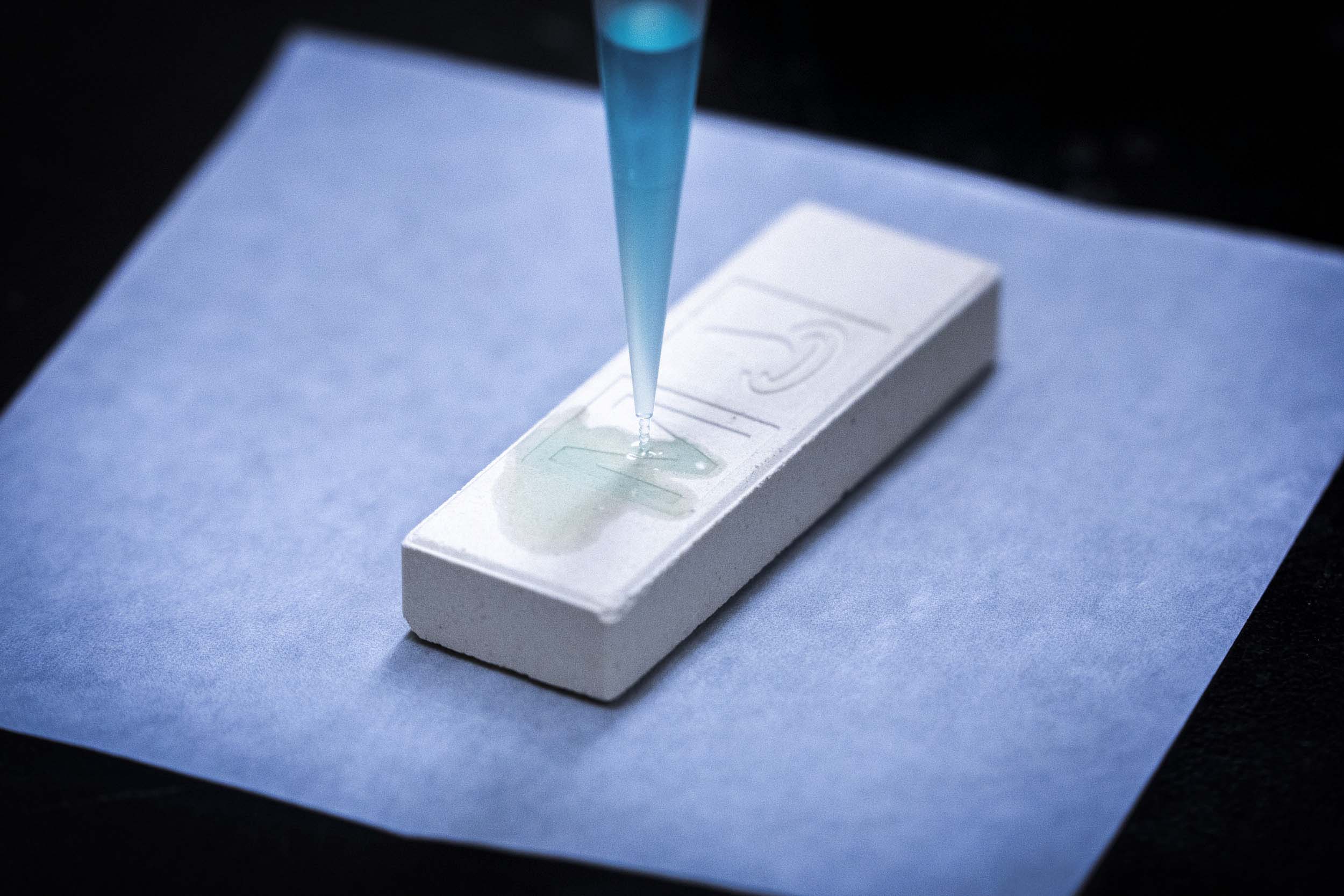

Initially developed in conjunction with a nonprofit organization called PureMadi – inspired by the Tshivenda South African word for water, “Madi” – Smith’s lab conducted extensive tests on a silver-embedded ceramic tablet capable of ridding drinking water of bacteria and viruses. In 2015, a UVA-inspired public benefit company, MadiDrop PBC, opened administrative and production spaces in Charlottesville. Two years later, more than 20,000 MadiDrop tablets had been distributed to humanitarian organizations around the world, primarily in Africa and Latin America.

In 2018, MadiDrop PBC was replaced with the for-profit Silivhere Technologies Inc. and developed MadiDrop+, an iteration of the tablet which quadrupled performance outcomes. One pocket-sized tablet – sitting at a unit price of $15 and costing less than 0.2 cents per liter – could treat up to 20 liters of water per day for 365 days, providing close to 7,000 liters of safe drinking water per family, per year.