Q. What was the scope of things you found that ended up being submitted as potential evidence for the investigation?

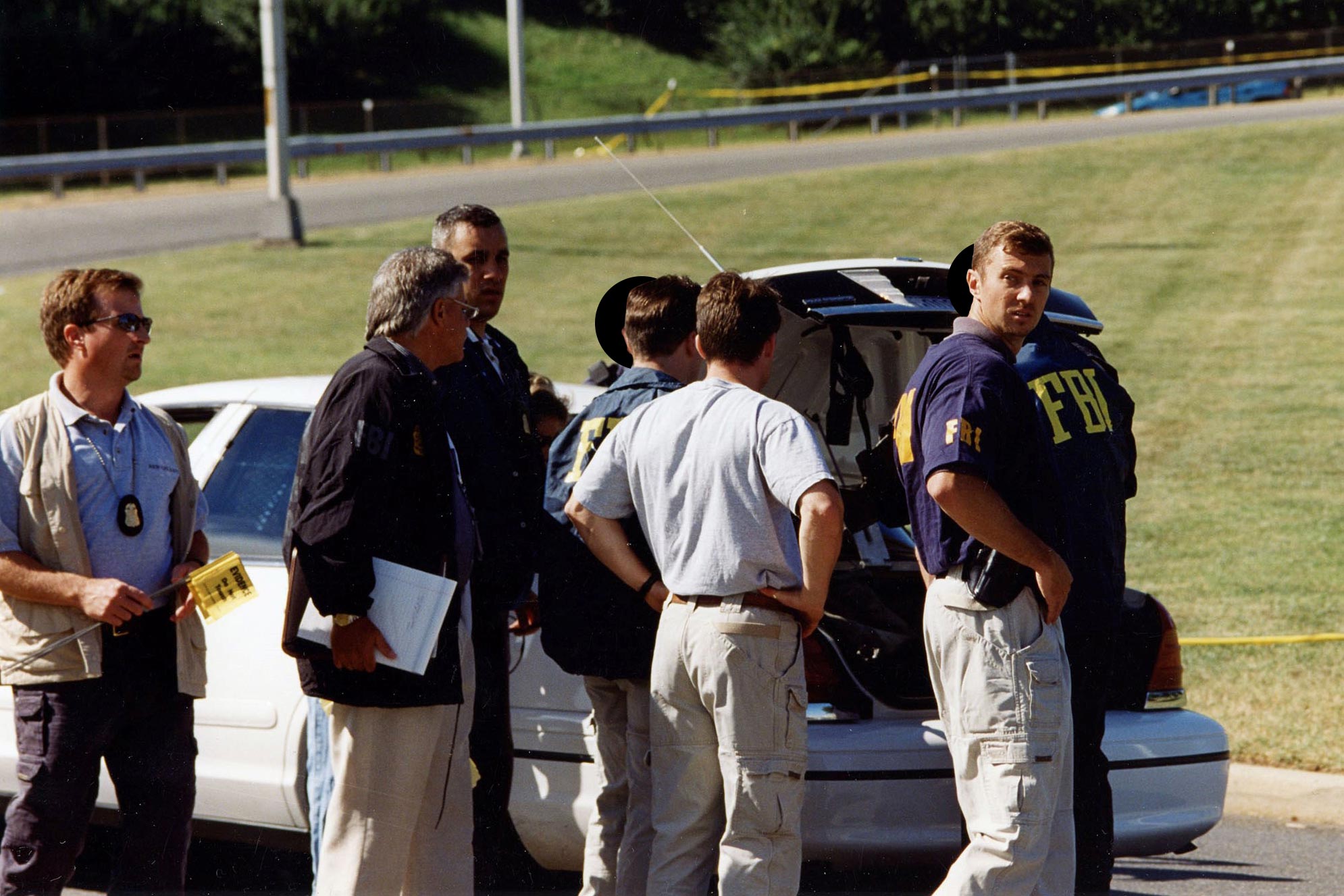

A. My piece was focused on collecting a wide variety of potential evidence from inside the Pentagon. We later also moved over to working on the parts that were coming out of the crater and going through that. Within there, among other things, was the driver’s license for one of the hijackers. And that’s the one thing that I can kind of remember personally resonating.

Q. What kind of license was it?

A. It was Virginia. That was part of the follow-up investigation that I ended up doing once I rotated back … and they assigned me to the squad that was investigating the case.

One of the early leads that we started running down was on how [the terrorists] acquired their licenses. So we found the people that were in line in front of them and in the back of them at the Virginia DMV. We interviewed them, and many others, trying to piece together all of the highjackers’ activities prior to the attack. What were they doing in Virginia leading up? Who were they talking to? Are there other people out there that we need to be concerned with? Are there other cells that we’re not aware of? We have to identify every last movement that they had while they were here and every last person that they ever talked to and go talk to them.

Q. The work of identifying bodies and victims – that had to be difficult to do, even for a person with your experience.

A. Yeah, I mean, certainly there’s an emotional reaction, but you have to put that in check in order to be able to do what’s necessary. And yet you think about the people that were going about their workday in an office and didn’t see this coming and they’re not going back to their families. I can remember vividly the time that I spent there at the Pentagon. I think it’s because of the magnitude of the event and the emotional reaction that’s burned into your memory. The end goal is you’ve got a job to do and you’ve got to do it.

Q. How old were you when 9/11 happened, and what kind of career path were you on at that time?

A. I was almost 30. Interestingly, I started off my career at Washington Field Office on the Terrorism Squad, and I had just recently moved over to a squad that was working narcotics, drug diversion and things like that in Washington, D.C. So my career path was certainly still undetermined at that point. Who knows where it would have gone without 9/11, but after 9/11 I was pulled back immediately to the same squad that I worked with before. They had the lead investigative role for the Pentagon attacks within the Washington Field Office.

Q. You mentioned when you’re under that bridge and thinking it was a Pearl Harbor moment that was going to change everything. At that moment, there was no way to know that your career was one of those things that was going to be completely turned around or put in a new direction by 9/11.

A. Absolutely right. I tell this to a lot of people, especially new agents coming into the FBI – you have ideas about what you want, what your career is going to be, but you have no idea how it’s going to end up. It depends on where you get assigned, what big case comes your way, what you get pulled into, and it could go down a completely different path than you ever imagined.

I read all the books about the way the FBI was able to build organized crime cases against the La Cosa Nostra [an organized crime entity]. And I really like piecing together and thinking creatively to use prosecution to take down big criminal organizations. That’s one piece that drew me to the FBI. Certainly I hadn’t ever really thought about terrorism, but the same types of investigative, creative, forward-leaning tools and techniques that were used to take down the mafia, the same types of things were used to go after terrorist organizations.

Q. Twenty years after 9/11, with your career having gone the way it’s progressed, has this work been rewarding personally and professionally?

A. Oh, absolutely. I mean, I can’t think of a better career. Very happy about my decision to join in and really grateful for all the opportunities.

Q. On the big-picture level, how is it meaningful?

A. Almost all of the violations we work are going to have victims – people who have been wronged and people who have done them wrong. People that have broken the law and have put some degree of pain and suffering on others. And there’s obviously a huge level of satisfaction in going after that. It becomes pretty clear that you’re on the side of what’s right.

Our job as counterterrorism investigators and the FBI, the priority is to identify and to prevent acts from occurring before they do. So that’s a little bit different. This is where I think it’s been so rewarding, because we’re working cases and we’re resolving them before they can act. Disrupting would-be attackers. We’re preventing really bad things from occurring and oftentimes without anybody even knowing. From a personal satisfaction standpoint for terrorism investigators, really that’s part of what drives us.

Q. Has the proliferation of technology, the internet and social media introduced a new set of difficulties?

A. Yes. Technology has evolved as an accelerator for how fast people can be radicalized, can go find like-minded individuals and inspiration to go conduct violent acts. It’s made it easier in some ways for them to go do that without being noticed. It’s changed from when you had to go and hang out in somebody’s basement and listen to some charismatic person face-to-face. You can do that online. You don’t have to travel overseas.

Also it’s challenging now in that your traditional terrorists are being copied. The tactics and techniques are being copied by those who are doing acts of violence that really have no connection to a terrorist organization. But they are still using violence as a way to solve their problems – your school shooter, other active assailants, mass attackers and things like that. That’s what I’ve been working on the last four years here.

Technology has definitely enhanced the challenge that we face.

Q. It’s hard to imagine, 20 years later, some malignant actors, either foreign or domestic, commandeering an aircraft and crashing it into something again. That’s not really the threat that you’re probably most worried about at this point, is it?

A. We certainly have to keep our eye on that threat ... that long-term, sophisticated, coordinated attack planning emanating from overseas. But what has really evolved over the last 10 years or five years, is that evolution of threat – actors who are motivated by a wide variety of ideological political motives and then personal motives, that are looking to use violence as a solution. How do we prevent those attacks from occurring the same way we’re looking to prevent others?

And it gets down to training and educating bystanders and making sure that they’re reporting information the same way we would have to report, say, someone leaving a backpack in a crowded subway. We want people to know how to recognize and report and where to report information about [someone] that they’re concerned is becoming obsessed and fixated on the idea of using violence to get back at people who have wronged them. And then how do we, as the FBI and all of our law enforcement partners and other stakeholders, how do we work together to effectively manage those threats? It has blossomed into more of this kind of whole-of-government and even whole-of-society approach.