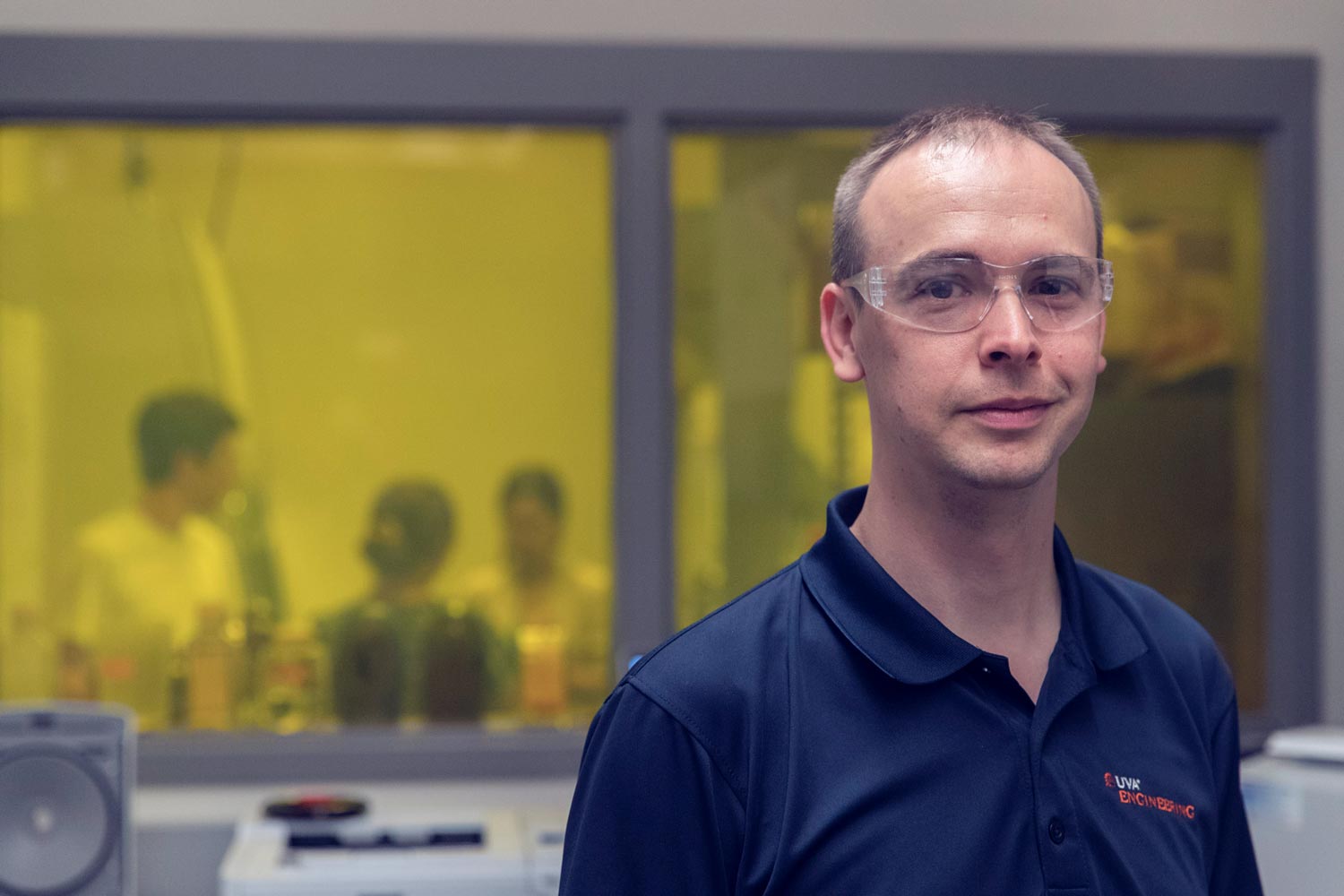

University of Virginia professor Kyle Lampe said the primary product of his chemical engineering laboratory is the next generation of scientists and engineers.

“That is why I am a professor,” he said. “I train people to do good science and engineering. I love what we do in the lab, but I think the actual research products that we make are a bonus. If that were my primary goal, I would probably be working at a biomedical company instead.”

Lampe, 37, recently was honored for his teaching by being included in the “20 Under 40” faculty group, as determined by Prism magazine, published by the American Society for Engineering Education. Many of those celebrated were selected on the basis of strong recommendations and early career awards.

“We can’t claim to have identified America’s top young engineering faculty members,” Prism magazine said in a published statement. “Nor were our ‘20 Under 40’ talents selected scientifically. But together they represent the variety – of region, discipline, type of institution, personal background and strengths as researchers or instructors – of the engineering education enterprise.”

A native of Iowa whose parents were teachers, Lampe said he appreciates Prism’s recognition, but is particularly pleased with praise from closer to home.

“For me it is more meaningful that my chair nominated me, and to see my chair say good things about me that lead to getting the award, than to actually get the award,” he said. “There are only 20 people and I know two of the others personally. It’s like making the all-star team, but I don’t feel as if I belong on the team with the rest of those people. A couple of those people are people I aspire to be like.”

William Epling, who chairs the Department of Chemical Engineering in UVA’s School of Engineering and Applied Science, praised Lampe for his concern for, and mentorship of, all of his students.

“He is dedicated to ensuring they are well-educated, well-rounded and well-prepared for their next steps,” he said. “This extends beyond ‘just’ his graduate students to his undergraduate researchers, also.”

In recommending Lampe, Epling cited some of his unusual pedagogical approaches to presenting the work and communicating with students. Lampe teaches a course on “Polymer Chemistry and Engineering” to 15 to 25 undergraduates annually, and another course on biochemical engineering.

“After I taught it once, I put the polymers course through the Course Design Institute, which is run by the Center for Teaching Excellence, a couple of years ago,” Lampe said. “It was an entirely restructured way of thinking how to design a course.”

Some of Lampe’s innovations include a team exam, where groups of three or four students complete an examination together.

“There is also an individual exam, so you can’t rely entirely on the intelligence and persistence of your teammates,” he said. “But it helps manifest that these folks do learn from each other. One of my students, after the first time we did a team exam, said, ‘That’s the first time I have ever learned something during an exam.’

“That is exactly the point. The individual exam is an assessment, but the team exam is meant to be another way to learn information.”

He also brings in guest lecturers from industries that apply polymer science.

“Klöckner Pentaplast is a local polymers company, and its people come in and talk about real-world applications of what we are learning,” he said. “They can discuss how you process these polymers to make them into a thin film so you can manufacture packaging for pharmaceuticals; how you laminate different polymers together and how you seal those up to create these individually packaged capsules.”

The students in his course have a semester-long team project, producing an infographic and then a short video to help them pitch their project idea to a lay audience.

“We watch everybody’s video in class so everybody learns a little bit more about what the other projects are, and that culminates with the most technical aspect, which is a 20-minute class presentation,” he said. “That is where the very technical elements come out, such as physical properties, the market, the business outlet, people who want to buy it, the customer base.”

He said some of the students have taken an engineering business minor, so some of the presentations have a business slant to them.

“I am continuously pleasantly surprised by what they come up with for these projects,” Lampe said. “They can be very creative; the videos especially are super-creative, which is one of the elements I grade them on. Creativity is explicitly one of the criteria.”

He said several years ago a student used the song “Call Me Maybe,” re-writing the lyrics to be specific to their polymer project, and made a music video for it.

Lampe also runs a research enterprise, operating a laboratory with five graduate and 10 undergraduate students this summer.

“It is a team effort, with everybody in the lab helping mentor everybody else,” Lampe said. “I hope I set a culture and identify some interest or talent to get them in the lab to begin with. I make sure it is a supportive environment.

“I am very proud of the fact that more than half of my lab is women. And to make that happen, we have to enable and support folks who want to do engineering research.”

Lampe spends significant one-on-one time with his graduate students, as well as having a weekly group meeting so he can interact with everybody. Each semester, and at least once during the summer, Lampe hosts a meal at his house for his students, a tradition which now ends with “science charades.”

“It is like charades, only the categories are more restricted,” Lampe said. “One of the categories has to be science. And you write clues for the other team and the other team writes clues for you. And you have people trying to act out Langmuir isotherm.

“I know what that is, and I can’t figure out how to act it out.”

Lampe’s research involves engineering tissue, such as myelin, the insulation for nerve cells. His work, which he hopes can relieve suffering in multiple sclerosis and stroke patients, leads to collaboration with people in a variety of fields.

“UVA has been great because I have been able to fit right in, in terms of the resources that were already here, such as an excellent neuroscience department,” he said. “I have to be somewhere that has a medical school, because I need to be able to talk to M.D.s and folks in biology and cell biology and neuroscience and neurology. I have a couple of mentors who are stroke neurologists and they are mentoring me, a chemical engineer.”

Lampe is a Translational Health Research Institute of Virginia Scholar, part of a program training researchers to advance clinical and translation science across Grounds and the state of Virginia.

“His collaborative spirit is also obvious and a strength,” Epling, the department chair, said. “Today’s big questions require teams with different skills to answer them. Kyle is collaborating with colleagues within the School of Engineering and Applied Science, the School of Medicine and the College of Arts & Sciences. These partnerships/teams allow him to gain a deeper understanding of the science examined, and thus more and better ideas in translating this knowledge evolve. This collaborative nature, of course, is also seen by his students, further providing them mentorship and preparation for their future.”

Lampe said he very much loves what he does.

“Getting to learn new things every day and help other people learn new things every day – that is what I love,” he said. “That is why I wanted this job.”

Media Contact

Article Information

July 13, 2018

/content/people-over-polymers-uva-chemical-engineer-educator-first