January 27, 2009 — Political cartoonist Patrick Oliphant communicated with two standing-room only audiences at the University of Virginia last week in the manner for which he is best known by newspaper readers across America — by drawing.

Called "the most influential cartoonist now working today" by the New York Times, Oliphant uses irony and an economy of line and words to, as he describes it, "vigilantly defend what our country stands for." Everyone is fair game — Republicans and Democrats alike.

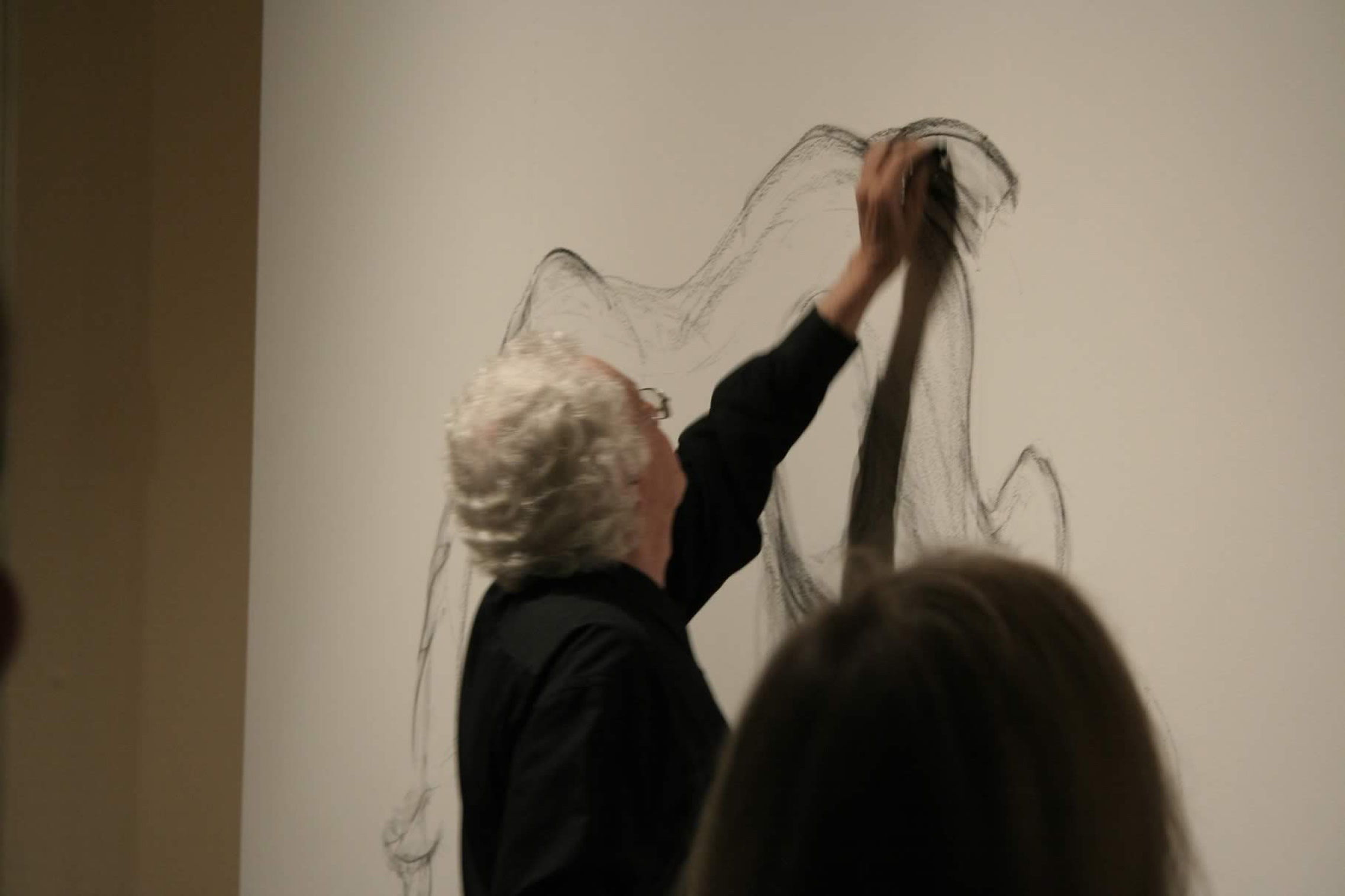

In front of audiences at the Miller Center of Public Affairs on Thursday evening and those gathered at the Harrison Auditorium on Friday, he drew caricatures of presidents and other political figures that were projected to let the audience witness his process. He shared that an essential element in his creative process is anger. "I bring myself to a boil every day. It doesn't take much," he said. "We've had eight years of good stuff. Satirizing the Bush years was easy."

He added, "I hate changes of administration. At least my villains have been in place for a number of years."

On Thursday, Oliphant chatted with George Gilliam, chairman of the Forum Program at the Miller Center. In response to Gilliam's list of his accolades and awards, including a Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning in 1967, Oliphant modestly responded: "Who's to say who's best at anything?"

A native of Australia, he said being an outsider gives him perspective and he likes to maintain that objectivity.

Often referred to as the dean of political cartooning, Oliphant has been honing has craft since 1952, when he began his newspaper career as a copyboy with the Adelaide News in Australia.

Punk the Penguin, the small character that appears in the bottom of many of his cartoons, was born when he worked at the Advertiser in Australia. Oliphant said he invented him as a way to get his own ideas into the cartoons and past his conservative editors.

P.J. O'Rourke, the conservative political satirist and correspondent for Atlantic magazine, a contributing editor of The Weekly Standard and author of numerous books, discusses Punk in the foreword he wrote for the catalog that accompanies the exhibit "Leadership: Oliphant Cartoons and Sculpture from the Bush Years," which is on view at the U.Va. Art Museum through March 8.

O'Rourke says some people interpret Punk as God, but he has another interpretation: "Pat draws Bad large and unattractive and doing things that aren't nice. He draws Good very small in a corner making wry comments to a miniature penguin."

O'Rourke and artist William Dunlap, both old friends of Oliphant's, joined him at the Harrison Institute Auditorium for the second presentation. O'Rourke and Dunlap quipped back and forth about each of the presidents as Oliphant drew his repertoire of caricatures.

Of Lyndon Johnson, Oliphant said he "was a godsend." Not only could he exaggerate his nose and ears, but Johnson's 10 years of war in Vietnam provided rich material.

When he had completed that drawing, he added a hood of black hair to LBJ. "Remember Golda Meir?" he asked. The crowd broke out in laughter.

As he drew a profile of Bill Clinton, O'Rourke quipped he "always thought of Clinton as a clown Kennedy."

When the topic of Al Gore came up, Oliphant put charcoal to paper, paused and then said, "He's so boring I can't think what to draw."

For George W. Bush, the huge 10-gallon hat on the tiny figure was a staple representation in Oliphant's arsenal. He drew him standing proud in his cowboy boots with training wheels attached.

Now that the Bush era is over, Oliphant isn't sure what he'll be able to do with President Obama. "He's already been sworn in twice," he quipped. "He's got tenure."

Oliphant began his U.S. career at the Denver Post, where his cartoons were nationally syndicated beginning in 1965.

To a question from the audience about advice to aspiring cartoonists, Oliphant's response was: "Draw every day."

Oliphant does just that. He rises early, reads the New York Times and The Wall Street Journal, checks news on the Web and starts drawing.

Of Oliphant's style, Dunlap said, "There is an economy of means. Pat does not put a line there that is not needed."

Oliphant's words were filled with awe as he talked about his hero, Honoré Daumier, who lived and worked in France in the 19th century. His work is on display in an exhibit, "With the Line of Daumier," alongside Oliphant's at the museum.

"It's a loose flowing way of drawing," Oliphant said. "They were all lithographs. They were all drawn on stone – a special piece of limestone, a little larger than the actual drawings that you see. The line can be sharp and it can be beautiful soft lines that he gets. It's very hard to do with a pen."

It's not only the quality and execution of Daumier's drawings that appeal to Oliphant. "He dealt in lawyers a lot. I love that. Beating the hell out of lawyers. And, absolutely anti-establishment is what a cartoonist is supposed to be.

"Whoever is the establishment — we are against it. That's the name of the game."

Called "the most influential cartoonist now working today" by the New York Times, Oliphant uses irony and an economy of line and words to, as he describes it, "vigilantly defend what our country stands for." Everyone is fair game — Republicans and Democrats alike.

In front of audiences at the Miller Center of Public Affairs on Thursday evening and those gathered at the Harrison Auditorium on Friday, he drew caricatures of presidents and other political figures that were projected to let the audience witness his process. He shared that an essential element in his creative process is anger. "I bring myself to a boil every day. It doesn't take much," he said. "We've had eight years of good stuff. Satirizing the Bush years was easy."

He added, "I hate changes of administration. At least my villains have been in place for a number of years."

On Thursday, Oliphant chatted with George Gilliam, chairman of the Forum Program at the Miller Center. In response to Gilliam's list of his accolades and awards, including a Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning in 1967, Oliphant modestly responded: "Who's to say who's best at anything?"

A native of Australia, he said being an outsider gives him perspective and he likes to maintain that objectivity.

Often referred to as the dean of political cartooning, Oliphant has been honing has craft since 1952, when he began his newspaper career as a copyboy with the Adelaide News in Australia.

Punk the Penguin, the small character that appears in the bottom of many of his cartoons, was born when he worked at the Advertiser in Australia. Oliphant said he invented him as a way to get his own ideas into the cartoons and past his conservative editors.

P.J. O'Rourke, the conservative political satirist and correspondent for Atlantic magazine, a contributing editor of The Weekly Standard and author of numerous books, discusses Punk in the foreword he wrote for the catalog that accompanies the exhibit "Leadership: Oliphant Cartoons and Sculpture from the Bush Years," which is on view at the U.Va. Art Museum through March 8.

O'Rourke says some people interpret Punk as God, but he has another interpretation: "Pat draws Bad large and unattractive and doing things that aren't nice. He draws Good very small in a corner making wry comments to a miniature penguin."

O'Rourke and artist William Dunlap, both old friends of Oliphant's, joined him at the Harrison Institute Auditorium for the second presentation. O'Rourke and Dunlap quipped back and forth about each of the presidents as Oliphant drew his repertoire of caricatures.

Of Lyndon Johnson, Oliphant said he "was a godsend." Not only could he exaggerate his nose and ears, but Johnson's 10 years of war in Vietnam provided rich material.

When he had completed that drawing, he added a hood of black hair to LBJ. "Remember Golda Meir?" he asked. The crowd broke out in laughter.

As he drew a profile of Bill Clinton, O'Rourke quipped he "always thought of Clinton as a clown Kennedy."

When the topic of Al Gore came up, Oliphant put charcoal to paper, paused and then said, "He's so boring I can't think what to draw."

For George W. Bush, the huge 10-gallon hat on the tiny figure was a staple representation in Oliphant's arsenal. He drew him standing proud in his cowboy boots with training wheels attached.

Now that the Bush era is over, Oliphant isn't sure what he'll be able to do with President Obama. "He's already been sworn in twice," he quipped. "He's got tenure."

Oliphant began his U.S. career at the Denver Post, where his cartoons were nationally syndicated beginning in 1965.

To a question from the audience about advice to aspiring cartoonists, Oliphant's response was: "Draw every day."

Oliphant does just that. He rises early, reads the New York Times and The Wall Street Journal, checks news on the Web and starts drawing.

Of Oliphant's style, Dunlap said, "There is an economy of means. Pat does not put a line there that is not needed."

Oliphant's words were filled with awe as he talked about his hero, Honoré Daumier, who lived and worked in France in the 19th century. His work is on display in an exhibit, "With the Line of Daumier," alongside Oliphant's at the museum.

"It's a loose flowing way of drawing," Oliphant said. "They were all lithographs. They were all drawn on stone – a special piece of limestone, a little larger than the actual drawings that you see. The line can be sharp and it can be beautiful soft lines that he gets. It's very hard to do with a pen."

It's not only the quality and execution of Daumier's drawings that appeal to Oliphant. "He dealt in lawyers a lot. I love that. Beating the hell out of lawyers. And, absolutely anti-establishment is what a cartoonist is supposed to be.

"Whoever is the establishment — we are against it. That's the name of the game."

— By Jane Ford

Media Contact

Article Information

January 27, 2009

/content/political-cartoonist-oliphant-visits-uva-share-his-representation-human-folly