On a quiet afternoon in the University of Virginia’s Scholars’ Lab, the faint whirring of a 3-D printer proclaims the slow resurrection of a lost civilization.

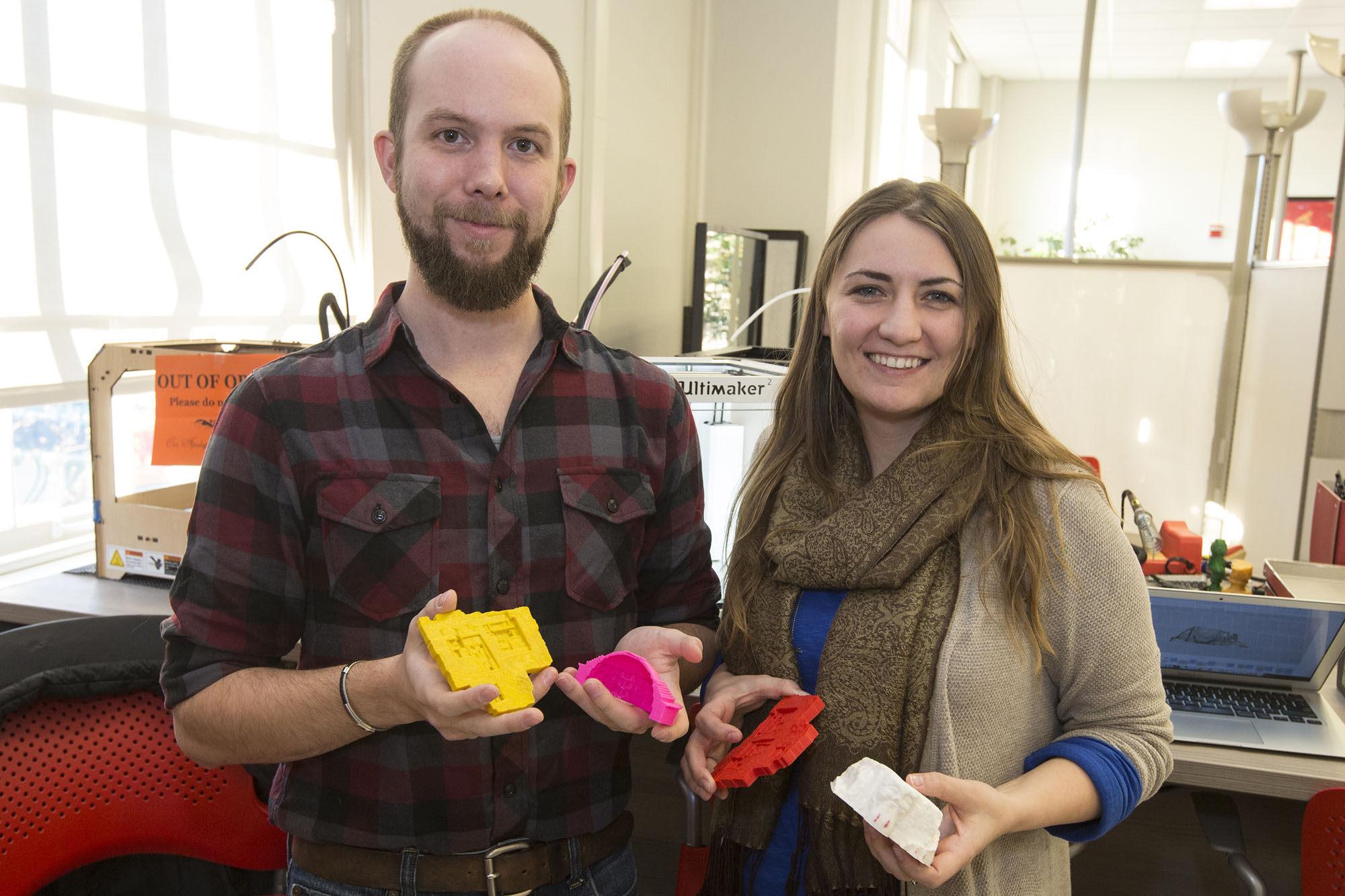

History of art and architecture doctoral candidate Jennifer Grayburn and classical art and archaeology doctoral candidate Benjamin Gorham are using the digital resources of the Scholars’ Lab Makerspace to recreate their remote archaeological findings in Sicily and Iceland.

“The Makerspace is part of the Scholars’ Lab and the intention is to have a place where people can tinker and experiment to integrate interactive objects into both research and teaching,” Grayburn said.

As the 2015-16 Makerspace Consultant, Grayburn helps students and faculty incorporate new technology into their studies. She also uses her own research into Norse medieval architecture to test new approaches to digital pedagogy. This year, she and Gorham are experimenting with ways to make fragile or immovable archaeological finds accessible to researchers around the world.

“One of our ultimate goals in using this technology for an archaeological site is to create an exhibition of objects that you can’t otherwise see away from the site,” Gorham said.

Graduate students Jennifer Grayburn and Benjamin Gorham hold examples of artifacts and archaeological dig sites they’ve recreated using the 3-D printer.

Dating back as early as the Bronze Age, Morgantina changed hands many times over the centuries and its ruins tell a rich story of Greek, Syracusan, Roman and Spanish influences.

Using a combination of aerial drone and on-the-ground photography, Gorham and the team in Sicily have made precise topographic images of their findings. Now, he and Grayburn are using those images to create 3-D-printed, scale models of what’s been uncovered.

The Morgantina site is very isolated and most of the artifacts have been sealed under layers of soil for thousands of years. This makes them extremely fragile; in many cases, the best way to preserve them is to leave them in place and document each finding extensively.

“That used to just mean sketching out the sites on paper or CAD [computer aided design],” Gorham said. “But now that we have this capability, we can actually ‘lift’ things out of the ground without really lifting them out of the ground. We do this by photographing the findings many times, weaving those photos together for a complete 3-D model, and then printing it.”

Last summer, the Morgantina crew focused on three trenches inside the sprawling ancient city. Using hundreds of photos, Gorham recreated the sites digitally and has been working to print a scale model of them for use in class and at archaeological conferences.

Click below to explore a 3-D rendering of the three newest Morgantina excavations.

Final2015Aerial by AEMCAP on Sketchfab

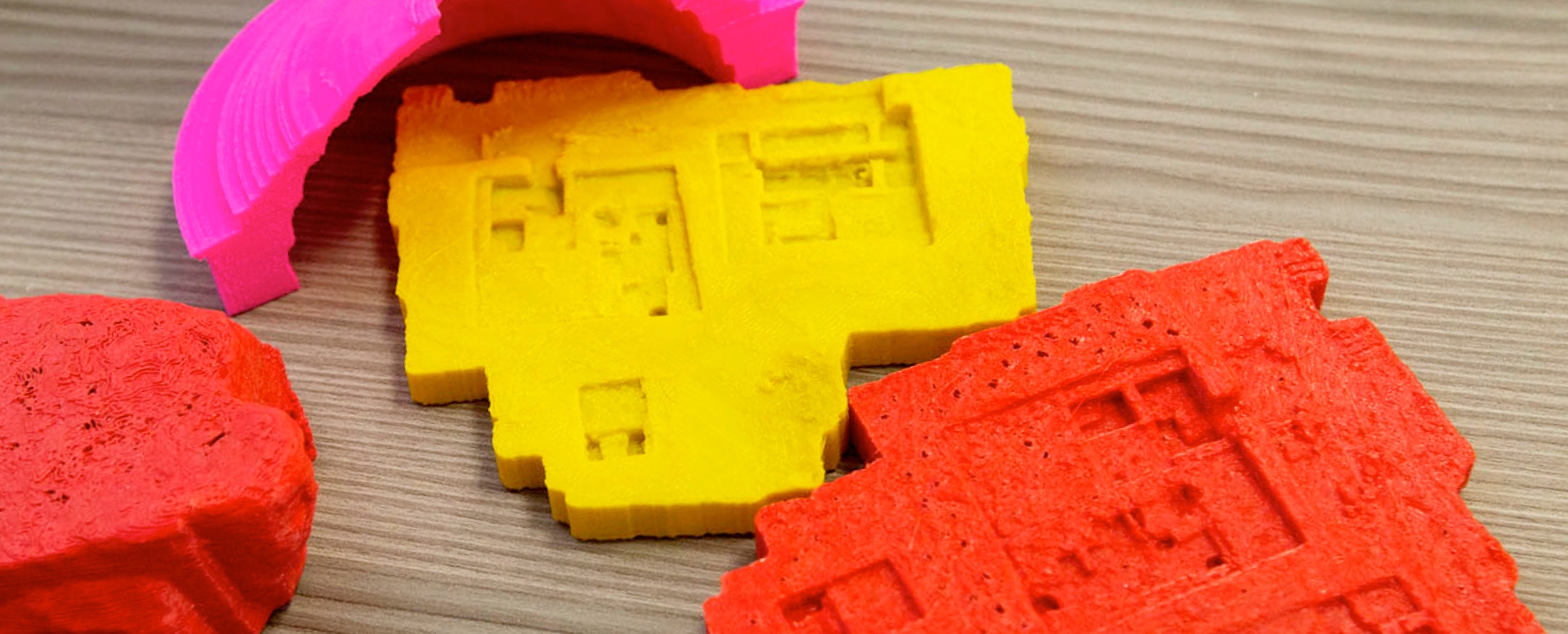

Despite the small scale, the Scholars’ Lab’s MakerBot printer is able to capture the kind of precise details that matter most to archaeologists. Upon close inspection of the replica, one can see ridges exposing where the ancient residents added different layers of wall over time, and the outlines of a large terracotta pot that curiously obstructs an entryway.

For now, all of the Morgantina replicas are done in whatever color of plastic Gorham and Grayburn have loaded into the printer that day, but they plan to create more sophisticated models in the future.

“When we start doing them on larger scale, I would absolutely love to paint them to resemble the actual ground soil types, the stone features and the terracottas,” Gorham said.

Grayburn has begun experimenting with painting and printing larger models of the Norse artifacts she’s been researching in Iceland.

“I’m slicing the 3-D models and printing them in pieces that we can glue together to get close to the size of the original item,” she said.

Right now, she’s focused on a large, 12th-century carved stone from Hítardalur, Iceland. Due to complicated Icelandic land ownership laws and limited local museum space, the stone must remain outside at the former monastery where it resides. Over the years, the harsh northern climate has eroded the original details of the carving and it’s at risk for further deterioration.

Over time the distinct carvings on the twelfth century Hítardalur stone have begun to fade. The 3-D recreation helps preserve the current appearance before it is lost to the elements.

Grayburn has also begun trying this kind of reproduction with other smaller artifacts that students might rarely get to see in person. By experimenting with a type of printing material that blends plastic with powdered metal, she’s been reconstructing Viking artifacts like belt buckles and decorative bracelets.

“What you end up with are metal objects that you can then tarnish. They react just like the true metal artifacts do,” she said. “So these projects are actually a way to reconstruct artifacts in their archaeological state.”

Grayburn and Gorham are excited by the possibility of performing the same kind of reconstruction techniques on bones that are found during archaeological digs. Having 3-D printed copies of bones found at similar dig sites would give archaeologists more points of comparison when trying to determine the origin of remains found at their own sites.

“The idea of open access to 3-D bone models opens so many doors,” Gorham said.

For new dig sites or smaller museums that don’t already have a number of artifacts, open access to printable digital models would provide a solid foundation of bone samples to assist with identification.

“The use of 3-D printing has always been based in this open-access community, and in the concept of open sharing to de-commercialize things and objects,” Grayburn said.

By expanding that kind of open access to their own findings, Grayburn and Gorham are making it possible for students and researchers all around the world to share in the burden and privilege of preservation.

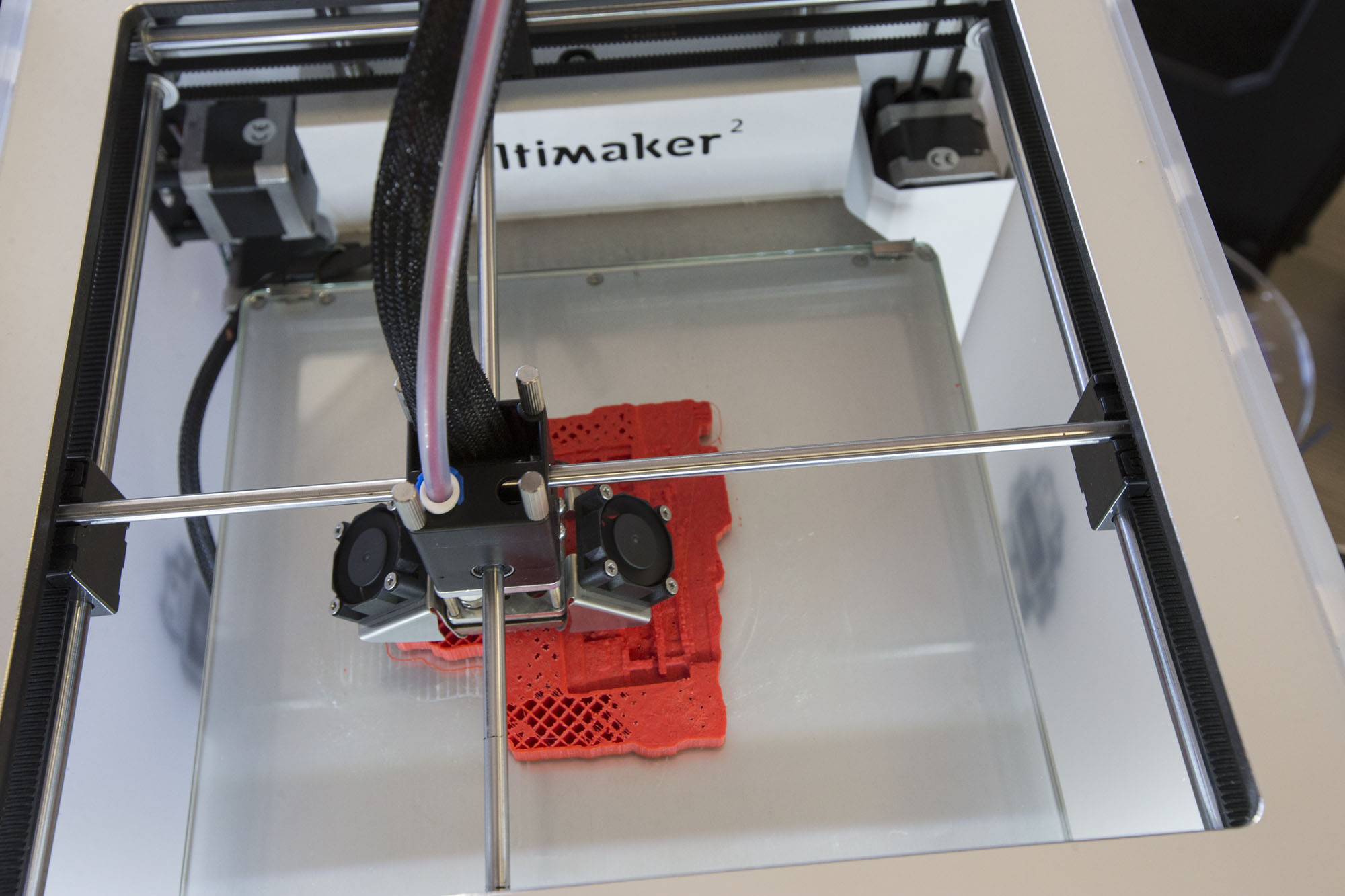

The Makerspace’s Ultimaker 3-D printer creates a detailed miniature of the Morgantina dig site in Sicily.

By documenting their work with precise 3-D models, Grayburn and Gorham are ensuring that even artifacts that are lost or stolen never truly disappear.

“That’s why open sharing and recreation is a huge deal,” Gorham said. “Even before it gets to the actual 3-D printed model, having these objects digitally in a format that we can post on websites and send to other parties amplifies our ability to build an audience and secure our findings.”

Media Contact

Article Information

January 25, 2016

/content/preserving-past-3-d