Amid an ever-increasing rise in drug-related death tolls across the country, President Donald Trump declared America’s opioid crisis a national emergency on Thursday.

The University of Virginia’s Christopher Ruhm, a professor of public policy and economics in the Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy, has been carefully tracking the crisis for more than a year, researching accuracy problems with drug overdose-related death reporting. The goal of his work is to provide a clearer picture of the scope and detail of the nation’s opioid epidemic.

In his new paper for the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, “Geographic Variation in Opioid and Heroin Involved Drug Poisoning Mortality Rates,” Ruhm uses statistical analysis to offer more accurate estimates of drug-related deaths on a state-by-state basis. He analyzes drug fatality rates for 2014, as well as trends between 2008 and 2014.

By accounting for those drug-related deaths where no specific drug was identified on the death certificate and adding them to existing death-certificate data where specific drug causes were reported, Ruhm offers corrected opioid- and heroin-involved mortality rates.

These corrected rates suggest that reported opioid and heroin mortality rates were off by 22 to 24 percent nationally, but with large variation in the errors across states.

For example, without corrections, opioid and heroin mortality rates were considerably understated in Pennsylvania, Indiana, Louisiana and Alabama, but barely at all in Rhode Island, Connecticut and Vermont. When it came to heroin deaths, the rates were seriously understated in Pennsylvania, Louisiana, Indiana and New Jersey but identified well in 14 states.

On the other hand, changes in opioid death rates, between 2008 and 2014, were considerably understated in Pennsylvania, Indiana, New Jersey and Arizona, but heavily overestimated in South Carolina, New Mexico, Ohio, Connecticut, Florida and Kentucky. Changes over time in heroin deaths were understated in most states with some of the largest underestimates occurring in Pennsylvania, Indiana, New Jersey, Louisiana and Alabama.

Christopher Ruhm is a professor of public policy and economics in the Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy. (Photo by Dan Addison/University Communications)

“There’s been a lot of discussion about certain areas having particularly high levels of risk, and what I find is that those levels aren’t necessarily incorrect when based on death certificate reports,” Ruhm said, “but this gives us a much clearer geographic picture of the epidemic’s spread.”

To learn more about his research methods and why more accurate reporting data is so crucial to combating the opioid epidemic, read the below Q&A from our 2016 discussion with Ruhm.

Q. What led you to believe that the existing death certificate data was problematic?

A. I began doing analysis of the data on death certificates not initially realizing that there was a problem. However, as I got into the research I discovered that, in many cases of fatal drug overdoses, the death certificates did not specify which drugs were involved. In reading prior analyses, I realized that other researchers were aware of this issue, but that no one had undertaken a systematic effort to address it.

Q. What important trends are we missing by not collecting better data on drug overdoses?

A. There are two aspects to this question. The first is that by lacking adequate detail on death certificates, we have a poor understanding of what drugs or combinations of drugs are involved in fatal overdoses. The second is that prior research has not done all that it could to identify the drugs involved in these deaths.

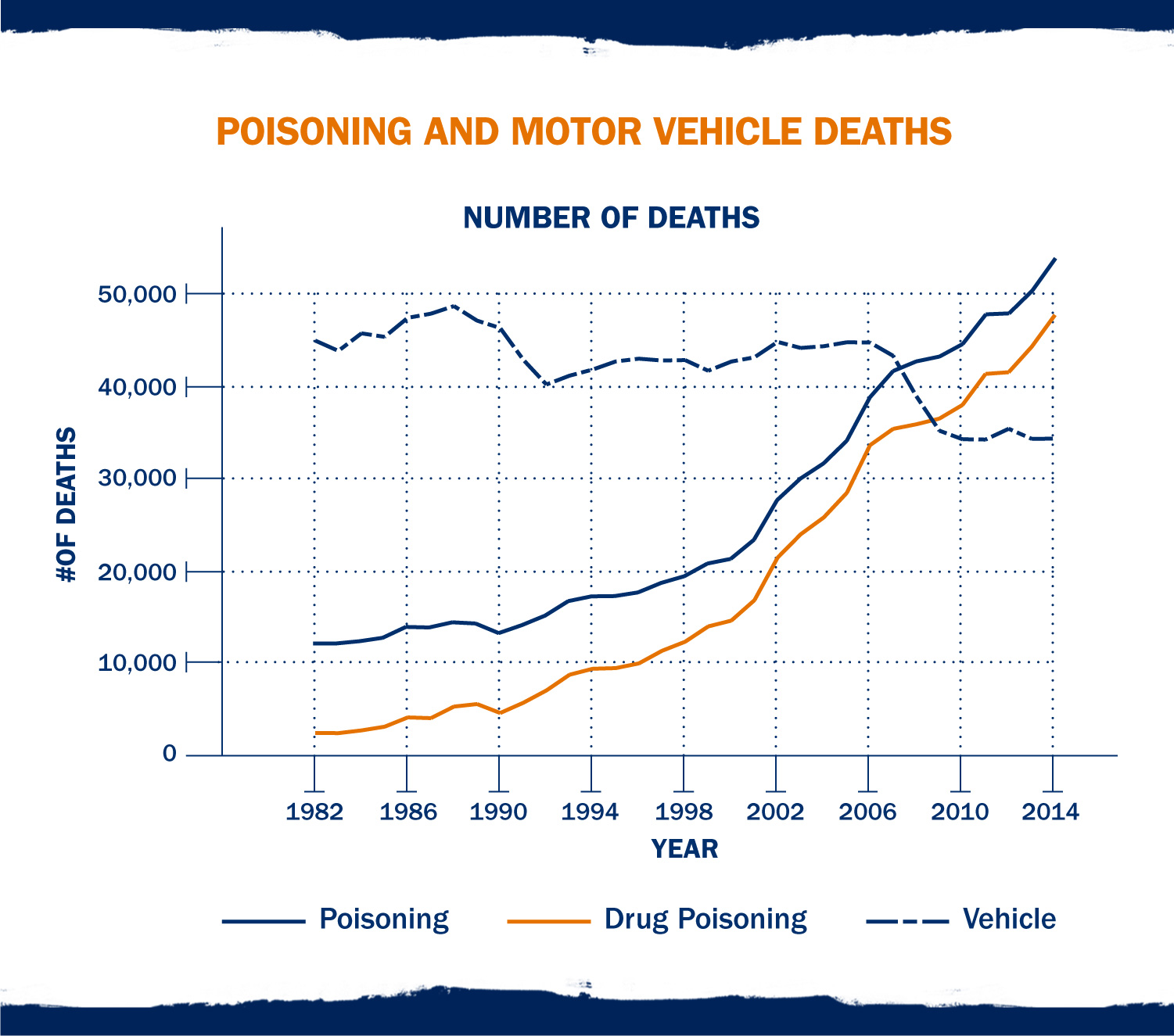

My analysis attempts to address the second issue, by using prediction methods to ascertain the drugs involved in cases where they are not well-specified on death certificates. Doing so substantially increases the estimates of the drug poisoning deaths involving combinations of drugs. For example, I estimate that drug combinations account for 56 percent of the increase in drug poisoning deaths occurring between 1999 and 2014, and 67 percent of that between 2007 and 2014.

Q. How have the primary culprits in the overdose epidemic changed since the 1990s?

A. Arguably, the overdose epidemic actually began in the early 1990s, or at least became much worse beginning then. From the mid-1990s through mid-2000s, this was led by increased use and deaths due to opioid analgesics (prescription opioids). However, since around 2008, and particularly since 2010, heroin has emerged as a major, and arguably the most important, problem. In addition, the use of drug “cocktails” – combinations of drugs – are driving much of the fatal drug epidemic.

Q. What portions of the population are most affected by this epidemic?

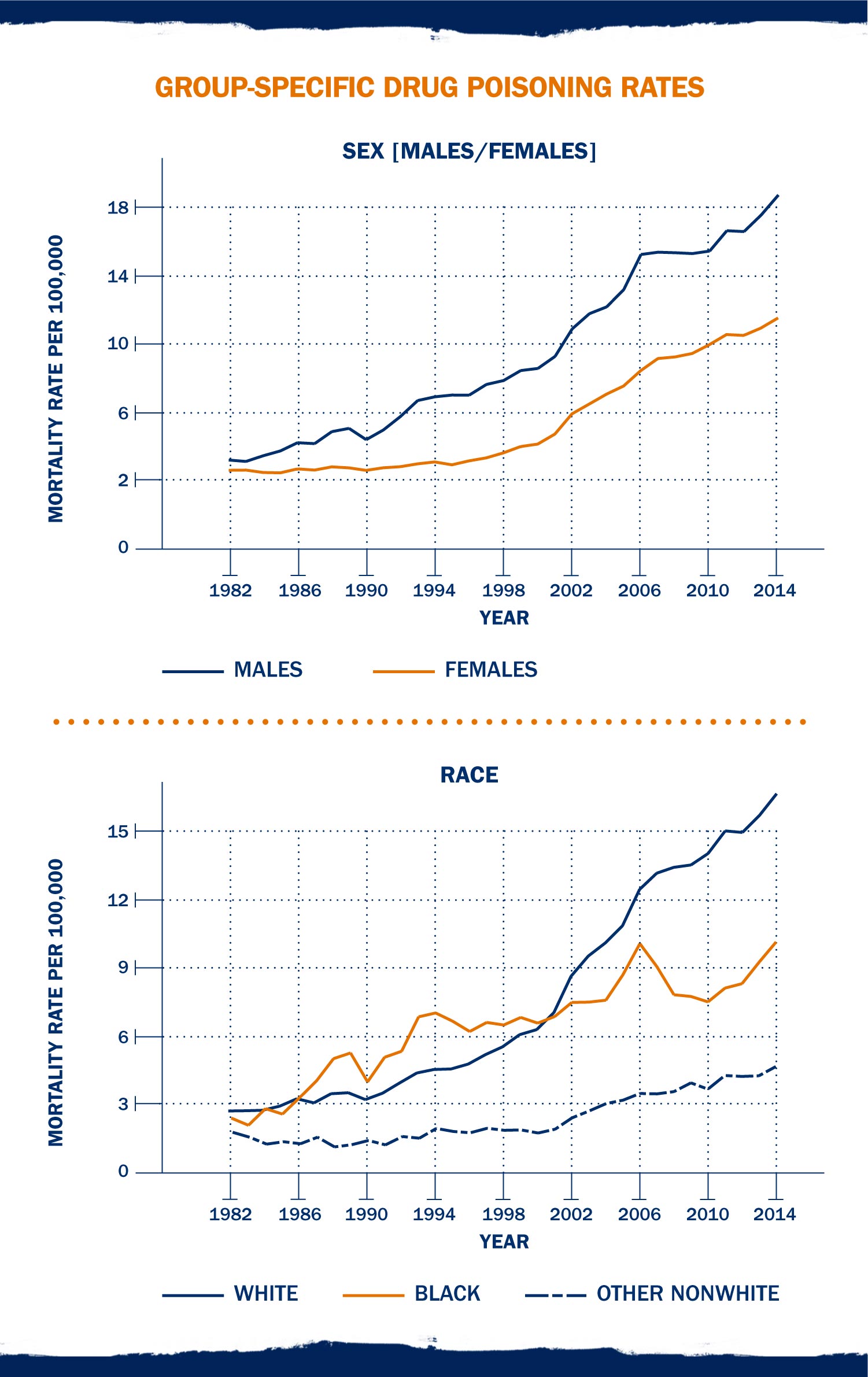

A. Fatal overdose rates are higher for males than females, for whites than blacks or other nonwhites, and for 25- to 64-year-olds versus those who are older or younger. Overdose death rates tend to be highest in “middle America,” particularly in Appalachia, the Rust Belt and many of the western mountain states. There are also pockets with high death rates in many other parts of the country as well.

Graph: Group-Specific Drug Poisoning Rates

Q. What possible policy solutions does your data point to?

A. First, we need to obtain better information and, until we obtain it, we need to creatively use the data that we have so as to better understand the nature of the fatal drug epidemic.

Second, we need to fully recognize and try to slow or reverse the rise in heroin-related overdoses and deaths. We have made some progress in recent years addressing the rising number of deaths related to prescription opioids, but problems related to heroin use and abuse are rising extremely quickly.

Third, we need to better organize our policy approaches and treatment efforts to the rising use of combinations of drugs, which frequently present greater risk than the use of a single drug type and may require more complicated and nuanced treatments and interventions.

A version of this story first published Aug. 18, 2016

Media Contact

Article Information

August 10, 2017

/content/professor-opioid-epidemic-even-worse-we-thought