For skygazers, this week marks the start of a once-in-a-lifetime chance to view a comet with the odd name of C/2022 E3 (ZTF).

The only rub is that the flyby might not be bright enough to see with the naked eye.

The comet is expected to brighten this week around Thursday, when it will be closest to the sun. Discovered in March by an automated sky survey telescope, the frozen flier will be closest to the Earth on Feb. 1.

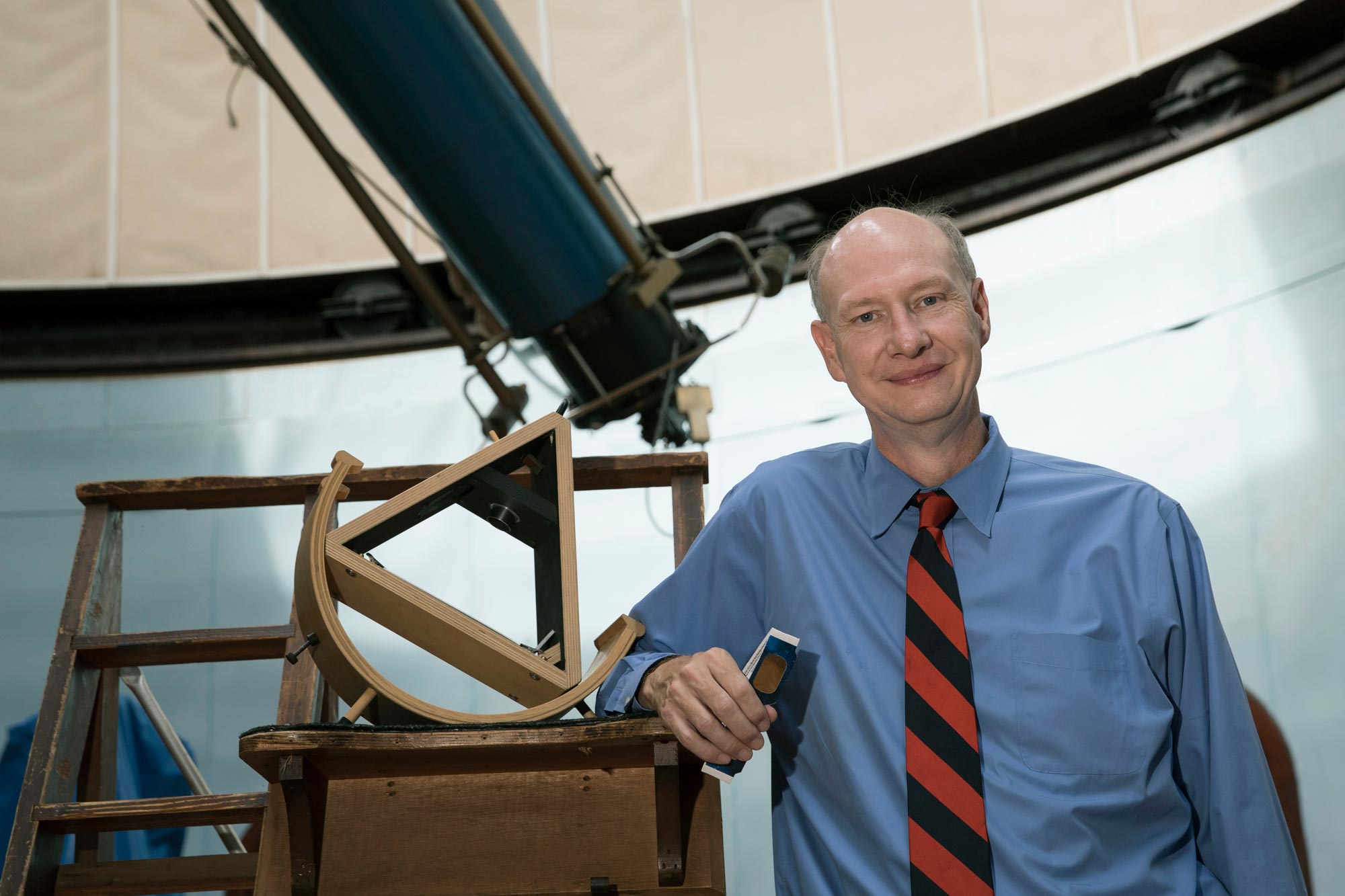

While it’s no Halley’s or Hale-Bopp, the coming of C/2022 E3 (ZTF) is still a reason to get excited, said Edward M. Murphy, a University of Virginia astronomer who plans to view it.

Murphy said that while the celestial display is predicted to be underwhelming compared to past comet visits, the fun is that we won’t know for certain until it gets closer.

“Comets are notoriously unpredictable,” Murphy said. “Based on the behavior of past comets and their distance from the sun and Earth, we can usually predict with some accuracy how bright comets will be. That said, every now and then a comet brightens much more than expected and puts on a great show. There is no way to know what this comet will do since it has not been observed in recorded history.”

If it’s a dud, the next opportunity to catch a glimpse will be in 50,000 years.

Now that we’ve tempered your expectations, here’s what Murphy says UVA Today readers need to know about comets in general and C/2022 E3 (ZTF) in particular, including potential viewing opportunities.

Q. What exactly is a comet? How is it different than an asteroid or meteorite?

A. Comets are giant, dirty snowballs. They are made primarily of water-ice and bits of rock and dust. As a comet approaches the sun, it warms up and the ice sublimates (turns into a gas), releasing water vapor and blowing chunks of rock and dust into space. These small chunks of rock and dust continue to orbit the sun like the comet. If the Earth were to pass through this trail of debris, we would get a meteor shower.

An asteroid is a rocky body in the solar system (as opposed to comets, which contain significant amounts of ice).

A meteorite is what we call a piece of an asteroid (or comet) after it falls to Earth. It is called a “meteor” as it streaks through the atmosphere.

Q. Can you explain a comet’s recurring flight patterns in relationship to Earth?

A. Most comets orbit the sun on highly elliptical orbits, carrying them close to the sun and then very far away. And for most comets, their orbital period around the sun is thousands of years or more. They move very fast when close to the sun, so they spend very little time in the inner solar system, and they move very slowly when far from the sun.

In the case of C/2022 E3 (ZTF), its orbital period is about 50,000 years. That is, it was last in the inner solar system 50,000 years ago, and it will not be back until around the year 52,000! At its closest proximity to the sun, it is about the same distance from the sun as the Earth. At its farthest, it is more than 2,800 times farther from the sun than the Earth.

Q. Is the Earth in any danger from the visit?

A. None whatsoever! The closest this comet will come to the Earth is 20 million miles (33 million kilometers). That is a very long distance!

Q. Will the comet look the same as it did to our Neanderthal ancestors, the last to witness it?

A. The comet will, very likely, behave the same as it did. It will warm up and shed gas and particles of dust and rock. How it appears to us depends on two critical factors: how close it comes to the Earth and how close it is to the sun at that time.

If the comet is closest to Earth around the same time it is closest to the sun, then the comet will appear brighter in the sky. On the other hand, if the comet is on the opposite side of the sun from us when it is closest to the sun, then it will be very faint.

That’s all to say that we don’t know the orbit well enough to know what the passage looked like when C/2022 E3 (ZTF) was last in the inner solar system, so we don’t know if it will appear the same.

Q. How does this comet compare to the more famous Halley’s Comet or Hale-Bopp?

A. Halley’s Comet and Hale-Bopp are both large comets. Hale-Bopp was likely a few times larger than Halley’s Comet. C/2022 E3 (ZTF) does not appear to be such a big comet, so it will not get nearly as bright as the others.

Q. Why does this comet have such an odd name?

A. Comets are given a designation and a name. The designation has information on the type of comet and when it was discovered and the name is usually named after the individuals that discovered the comet. This comet is known as C/2022 E3 (ZTF). The “C” means that this is a non-periodic comet (it has an orbital period greater than 200 years). It was discovered in 2022 in the fifth two-week period of the year (E). It was the third comet discovered in that two-week period (thus, E3). The comet was discovered by the Zwicky Transient Facility, an automated survey of the sky using the 48-inch Oschin Telescope at Palomar Observatory in California, which is abbreviated ZTF.

The name is in parentheses because it is not yet official (that is, the International Astronomical Union has not approved the name yet). Had it been discovered by a person rather than an automated survey, it would have that person’s name. They can have multiple names if people discovered the comet independently. For example, Comet C/1995 O1 Hale-Bopp was independently discovered by Alan Hale and Thomas Bopp.

Q. What’s the lowdown for best possible viewing of the comet this month and next?

A. I suggest that you find a good star map that has the position of the comet indicated on it. For example, the star maps at Skymaps.com show the position of the comet in the evening sky in late January around the time that the comet is closest to Earth. You can also find maps in Sky and Telescope magazine, Astronomy magazine or online. You will need to use a pair of binoculars or a telescope to see the comet. If it does brighten as expected, it might be barely visible to the naked eye under dark skies with no light pollution in late January or early February.

Q. Does UVA’s observatory offer any public viewing opportunities?

A. McCormick Observatory is open for public viewing on the first and third Friday evenings of every month. You can register to attend using the links on our website.

We are also open to educational groups (that make advanced reservations) on the second and fourth Friday evenings of every month.

Q. What are your own watch plans?

A. It all depends on what the comet does! If it behaves as expected and does not get very bright, I will likely just take a few pictures of the comet using a robotic telescope at Fan Mountain Observatory. If it surprises us and gets much brighter, then I will definitely go out and see it under dark skies.

Media Contact

Communications Manager School of Engineering and Applied Science

williamson@virginia.edu (434) 924-1321

Article Information

September 17, 2025