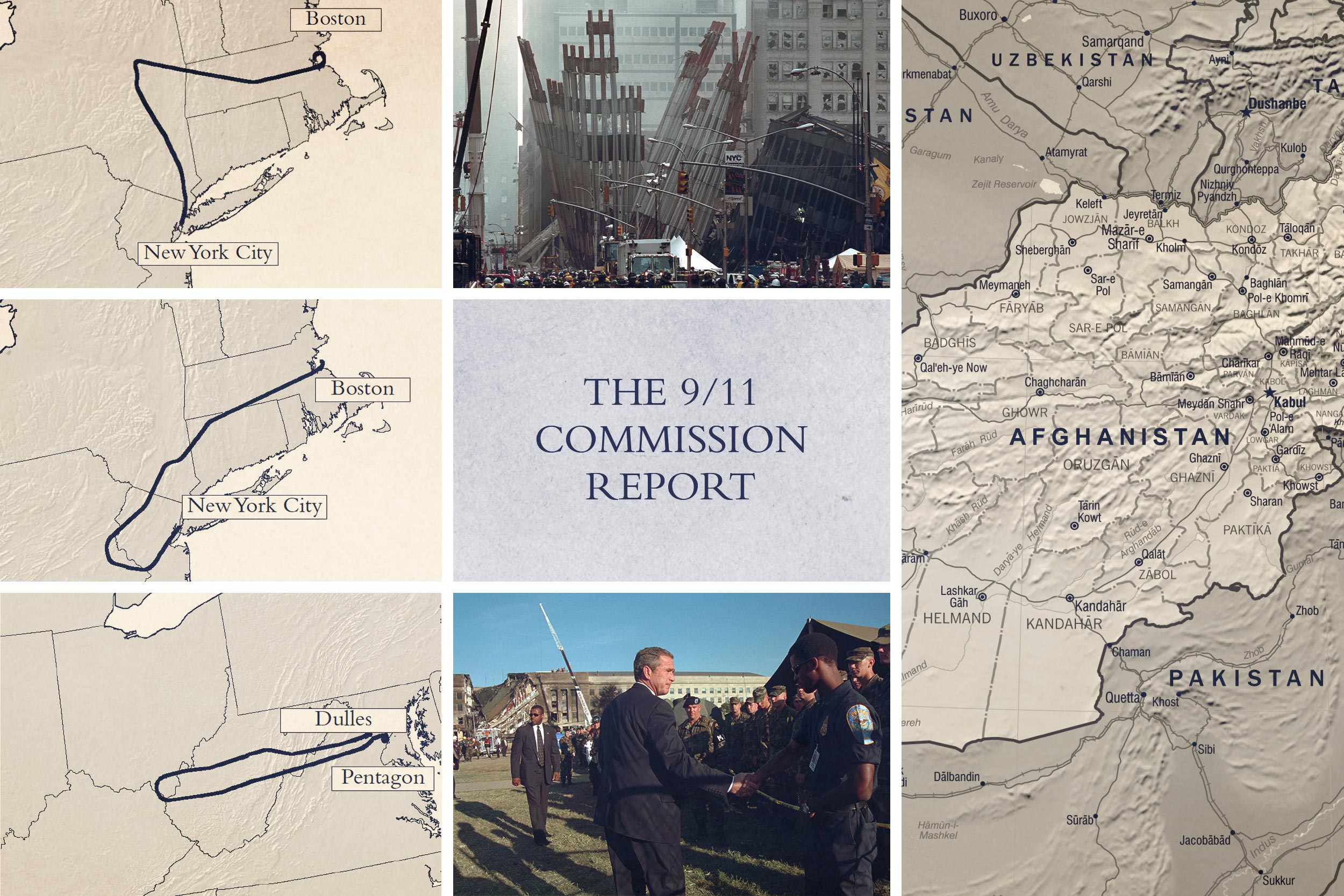

Before the attack, there was a lot of concern about tracking terrorists’ money, which in this attack was a trivial consideration. What our investigation showed and what turned out to be extremely interesting was not tracking terrorist money, but tracking terrorist travel. To launch an intercontinental operation, these people had to pass through several international portals in which they had to have documents that had to be examined, and those were the places they were most fearful of being caught. In fact, one of the would-be hijackers was turned back by an immigration inspector in Florida and did not participate in the hijacking, but he was the only one who got stopped.

After 9/11, the whole approach to regulating travel and travel documents changed. People are barely aware of it now, but they supply travel information before they board airplanes and that information is actually examined by government authorities to see if anyone suspicious is on the airplane, and the result is that intercontinental travel by these operatives, especially if they are carrying suspect documents, is now somewhat hazardous. For them, a relatively small risk can be catastrophic because, if they are caught, they might spend the rest of their lives in prison. So, the focus on terrorist travel became a key part of our layered defense system. But the whole significance of that was not well understood until the whole commission report came out. By taking stock of this thing and helping people rethink this problem, you actually change the whole way strategies adjust to the threat and make us safer in ways that don’t get into the creation of this or that institution.

Q. Is it true that terrorists need only to succeed once, while the defenders need to succeed all the time?

A. It almost works the exact opposite in reality, because when the terrorists move and operate, they are the ones who need to succeed all the time. If they make one misstep, they can be killed or captured.

Therefore, what has happened is they have tended to fall back on suicide attacks close to home – where they can launch their operatives without much interference, where they don’t have to cross borders and get past customs inspectors and take their chances at getting caught because they are going into foreign, strange places.

It doesn’t mean that those attacks are impossible. They are still possible; they are just harder. There are a lot more people looking for them, and the consequences of being found can frequently be career-ending.

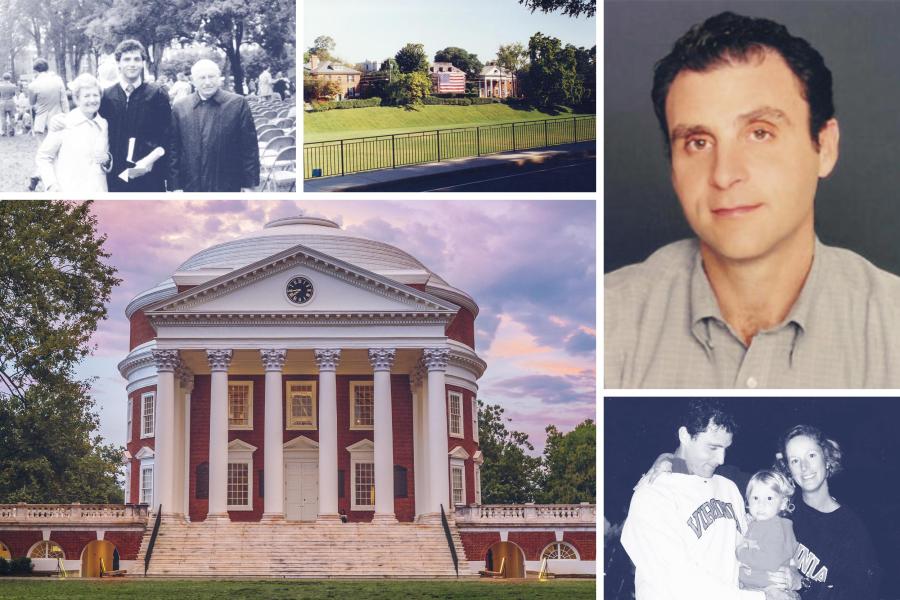

Q. What were your expectations going into the commission and how does it appear looking back?

A. I was blessed to be the leader of such a capable staff. We were working for 10 commissioners and I was the leading full-time employee, but there were more than 80 staffers involved. At the time we took on the job, we did not realize the work would be as stressful as it became, partly because of difficulties with the [President George W.] Bush administration and a fraught political environment.

On the other hand, I think my fellow staffers share a strong and enduring sense of pride for the quality of what we produced. The actual fact-finding we produced has held up astonishingly well. Now, 17 years after the report came out, there is hardly a full sentence in the report that needs to be revised in light of subsequent information. That may change as some of the people captured are put on trial and maybe some new facts will come out.

We never thought the report would be the last word on the attack. We thought it would provide a good foundation for further work and understanding, but the fact-finding in the report has held up very well.

The report turned out better than many of us might have anticipated going in. The quality of the collective work turned out to be very good and the report was very widely read and still is today.

I think if you asked any of the commissioners or any of the former staffers how they feel about it, I think almost all feel a great sense of pride. And I certainly share that. I am proud to have led such an extraordinary group of professionals.

Q. What did you learn in preparing the report that surprised you?

A. There were a lot of things. Going in, the understanding of what happened was actually not very clear. And a lot of the preliminary work that had been done by congressional committees had focused overwhelmingly on the intelligence community, assuming that was the source of the major issues, but a lot of the key issues were not actually intelligence issues. Some were policy issues that had been overlooked. This is often the case; people focus on things and they develop immediate narratives, and the narratives turn out to be substantially misleading or incomplete.

We didn’t realize that the basic narrative of what had happened that morning, put out by the United States Air Force, was wrong. This is the narrative the Air Force had made public and even told the president. Just the simple timeline of exactly what happened, when jets were scrambled, what those jets did, just the fundamental nuts and bolts of what happened that morning, was wrong. The Air Force and parts of the FAA had not done sufficient homework to reconstruct accurately what had happened. They made it sound as if their response was really quite coherent and that they almost got there in time and that they would definitely have intercepted United 93. None of those things were true.

And some substantive details about where jets went were wrong. And we ended up having to reconstruct that story. We had to use subpoenas, go back to the actual tapes and a lot of the raw technical information and reconstruct that story – and then oblige the Air Force to publicly correct it, admitting that our reconstruction was correct.

We had understood, and the country had understood, virtually nothing about what had happened in covert action plans or potential strike plans to try to defeat al Qaeda before 9/11. Almost nothing was known about the covert actions, approved and not approved. And the stories behind that turned out to be stranger than fiction. Nor did anyone know the details of the previous strikes that had been developed against bin Laden before 9/11 and then not authorized for various reasons.

Even a fairly specific illustration of a surprise we didn’t know – that at the beginning of August of 2001, an intelligence item landed on the desk of the director of the CIA headlined – headlined – “Terrorist Learns to Fly.” This is in August of 2001. And this was an item reporting on the arrest of a puzzling suspect in Minnesota named Zacarias Moussaoui, who, we later learned, was in training to be part of a second wave of pilot hijackers. Zacarias Moussaoui was a problem person, he had not been well-selected by bin Laden for this mission. He messed up in flight school and drew the suspicion of everyone around him and was arrested by the FBI about a month before the 9/11 attacks. This arrest was reported with that headline to the director of the CIA at a time when the director of the CIA was very worried that terrorists were going to attack us somehow, somewhere. But no one made a connection between that item, that arrest and the general worries about an al Qaeda attack somewhere. So there was no aggressive response to the Zacarias Moussaoui arrest until after 9/11, when we found out immediately about his various ties. That was a surprise.

And also we found out, including from interrogations of captured terrorists, that had the leaders of the 9/11 operation known that Moussaoui had been arrested, they probably would have cancelled the operation. But they didn’t know that. They didn’t know he’d been arrested, and they didn’t know how vulnerable they were – because as soon as Moussaoui was arrested, the communications and financial links from Moussaoui go back to the same people who were communicating and financing the 9/11 hijack team, and they would have known that was discoverable. These are all illustrations of the many things that we discovered in the course of our work that had not been discovered before.

The commission is a real testament to massive, serious investigations of these major events. People should not assume that even the best journalists who interview a handful of sources can achieve what a massive, systematic investigation can, if it is properly organized and run.