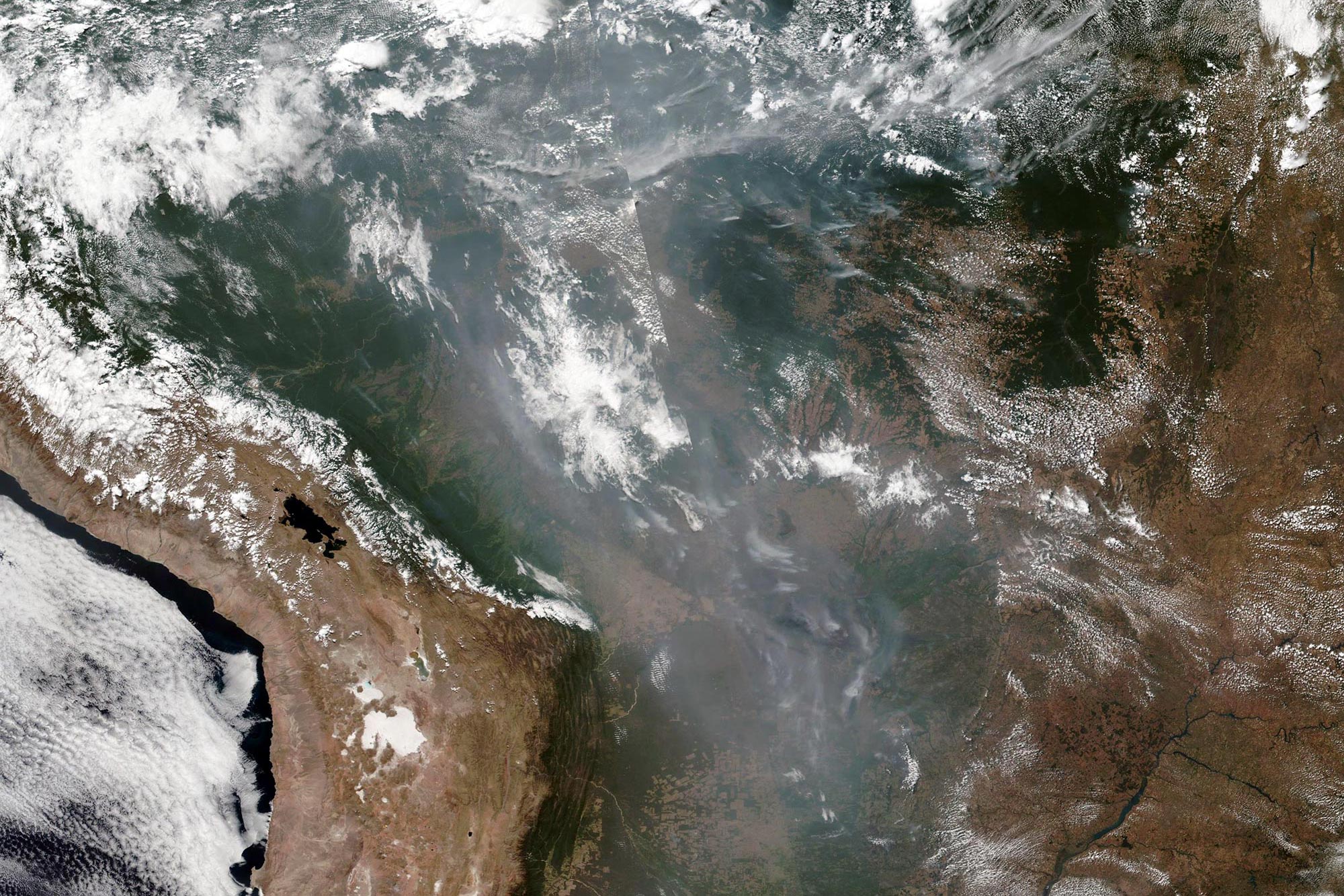

Thousands of fires are burning across Brazil’s Amazon rainforest, most reportedly set by farmers and ranchers as a means to clear land for cultivating crops and raising cattle. The vast Amazon forest is important to the health of the environment of that region, and also to global climate stability.

Deborah Lawrence, a University of Virginia professor of environmental sciences and Environmental Resilience Institute member who studies the links between tropical deforestation and climate change, discusses the situation for readers of UVA Today.

Q. What is causing these fires, and how extensive are they?

A. In a rainforest, fires are caused by people. People are clearing rainforest in the Amazon to create cattle ranches or soybean farms. But the number of individual fires is almost double what it was last year, up significantly after a decade of low forest loss.

We have to ask, why the sudden increase? Since Jair Bolsonaro became president of Brazil on Jan. 1 this year, he has removed real and perceived barriers to deforestation, failing to enforce many of the existing laws on forest clearing. The fires continue, so the extent of damage is not yet known.

Q. Is this permanent damage, and a serious threat to the Amazon forest?

A. Clearing and burning a rainforest takes a lot of work, and people are doing it for a reason: to change the forest into agricultural land. This is a permanent change, absent major efforts to restore the forest.

The real threat is if one year of massive forest loss like this one becomes 10 or 20 years. Brazilian scientist Carlos Nobre estimates that the Amazon could reach a tipping point if approximately 25% of the forest were lost. Deforestation could trigger changes in regional rainfall and temperature patterns, increasing tree mortality and enhancing the risk of catastrophic fires. Ultimately the forest would be replaced by shrubbier, sparser vegetation.

Currently, 17% of the Amazon has been deforested. It took about 50 years to get to this point. How fast it goes from here depends on the government of Brazil.

Environmental sciences professor Deborah Lawrence studies the interactions of forests and climate. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

Q. What can be done to sustainably manage these forests?

A. Over the past decade, Brazil did a lot of work to reform the laws regulating forests. As a result of public engagement and enforcement, deforestation plunged 80%.

The best thing they could do now would be to enforce existing laws. Ironically, one of the best ways to sustainably manage forests is to better manage agricultural lands, improving herd management and farming practices, boosting productivity and limiting the need to bring new land into production.

Strengthening legal protections for indigenous people and indigenous forest reserves would also help, as deforestation is lower in lands managed by indigenous people.

Q. What are the effects of these fires on the environment of the rainforest generally?

A. Smoke can change the way clouds form, potentially altering the timing and location of rainfall for a while.

The loss of all the tree trunks and the forest canopy changes everything after a fire – all that living biomass determines the way energy and water move in, out and through the system. Flood risk should rise, as water flows across the land rather than down into the soil or up through trees into the atmosphere.

While animals can escape fires in the short term, their habitats have been destroyed. It may take a while for pollinators and seed dispersers to find new host plants.

The plants, fungi and mosses that make their home on the trunks and branches of trees cannot escape.

Q. Why is the Amazon rainforest important to global climate, and does this have an effect on the climate long term?

A. Tropical forests are a critical part of the global climate system because of their role, day-in and day-out, managing the energy coming from the sun. Tropical forests use that energy to sequester carbon and move water, two processes that affect the global climate system.

The Amazon is the largest tract of remaining tropical forest. It holds a vast amount of carbon in vegetation and soil, accumulated over hundreds to thousands of years, and every year it stores away more carbon. Trees use CO2 to grow – the Amazon is so vast it helps to keep the concentration of atmospheric CO2 low and thus global temperatures lower than they would be otherwise. So, we are cooler in the U.S. thanks to the Amazon and other tropical forests.

Second, forests move massive amounts of water from the soil, through the trunks, out the leaves and into the atmosphere. This transformation of liquid water to water vapor cools the atmosphere above the forest, creating patterns of air flow. Because the atmosphere is connected across the globe, what happens in the Amazon propagates around the world, triggering changes in rainfall and temperature. In a warming world, we can’t afford to risk destabilizing rainfall patterns by deforesting the Amazon. We will face plenty of challenges as it is.

We are focused on the Amazon today, but losing the tropical forests of Africa and Asia would also disrupt the climate system, bringing excess rainfall to some regions and drying out others.

Not only those who grow food, but those who eat it should be concerned about the fate of forests around the world. Our global food system looks increasingly like our global atmosphere – it is all connected, and bumps in one place can produce dangerous vibrations in another.

Media Contact

Article Information

August 27, 2019

/content/qa-tropical-forest-researcher-warns-amazon-fires-may-have-global-impact