Over nearly a year of life in a global pandemic, words and phrases like “masking,” “social distancing,” “quarantine” and “herd immunity” have jumped into public conversation and stayed there, shorthand for what we are all going through.

Now, it’s “variant.”

Over the last few weeks, members of the medical community and public health officials have been laser-focused on emerging variants of the COVID-19 virus. The three most prominent have surfaced in the United Kingdom, South Africa and Brazil.

The U.K. variant, called B.1.1.7., is estimated to be roughly 30% to 40% more contagious. It spread rapidly through Britain and has now been detected in more than 70 countries and 40 U.S. states. UVA confirmed on Friday that this variant has also been detected in the University community.

While currently only accounting for about 1% to 4% of SARS-CoV-2 infections in the U.S., officials expect the U.K. variant will become the dominant variant in the U.S. over the next month or so, as it is doubling every day.

The South Africa variant, B.1.351, has spread less widely – to at least 24 countries and eight states (including Virginia) – but evidence suggests it evades COVID-19 vaccines more than the U.K. variant.

The Brazil variant, P.1, is similar in structure to the South Africa variant and has been detected in several countries and two U.S. states. Another variant, CAL.20C, has recently emerged in California, and is believed be responsible for about half of the COVID-19 cases in the Los Angeles area. It is not yet known if this variant is more infectious or deadly than the original.

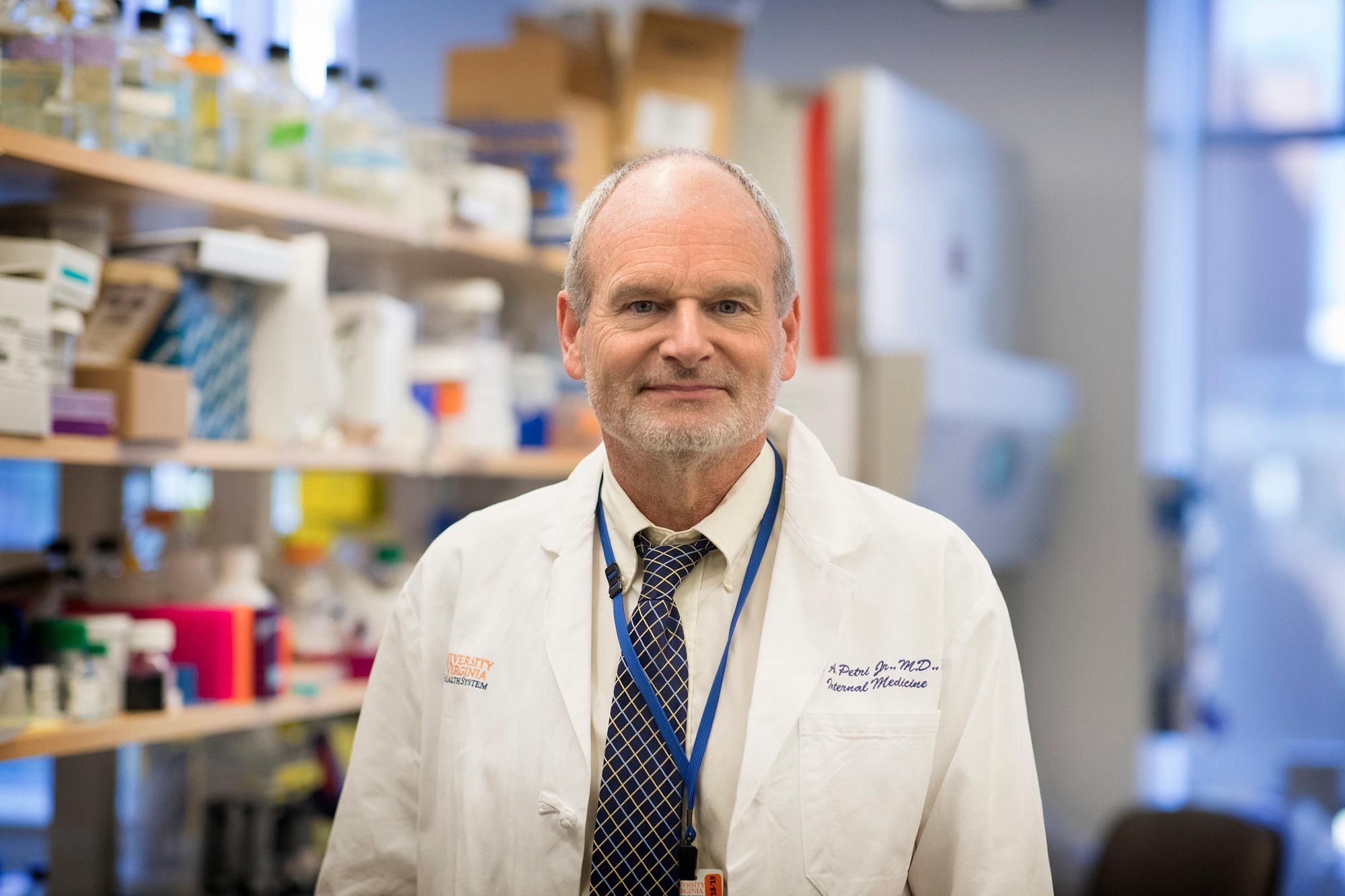

The three main variants, UVA’s Dr. William Petri explained, have developed, through convergent evolution, a single amino acid change in the spike glycoprotein that enables the virus to bind tighter to the human receptor for the new coronavirus. It is this ability of the virus to bind with higher affinity to the human ACE2 receptor that is believed to be the reason these variants are more easily transmitted person-to-person. We asked Petri, chaired professor of infectious diseases and international health at the University of Virginia and vice chair for research in the Department of Medicine, to explain how variants work and what they might mean in our fight against COVID-19.

Dr. William Petri is a chaired professor of infectious diseases and international health and vice chair for research in the Department of Medicine. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

Petri’s lab is among those at UVA studying COVID-19’s effects on the immune system, and seeking new treatments and vaccine possibilities. Most recently, his lab helped test an antibody cocktail that was shown to block 100% of symptomatic infections among people exposed to the virus.

Regarding the new variants, Petri said the biggest problem is time. The more the variants spread, the more time it will take us to reach herd immunity through vaccinations, and the more time the virus will have to mutate again. Adapting vaccines to protect us from variants is possible, he said, but would again take more time.

Learn more:

Q. Can you explain how a virus like COVID-19 mutates?

A. Of the RNA viruses we know of, coronaviruses in general are some of the most genetically stable viruses. They mutate at a much lower rate than influenza or HIV, for example. This is because they have a “proofreader” that removes mutations. The virus must replicate its genome with high fidelity, because it has one of the largest genomes of any RNA virus; it is three times the size of HIV. Given that size, without proofreading activity, mutations could disrupt the genome and make it noninfectious.

That is why these variants are showing up relatively late in the pandemic. It is a reflection of the slow mutation rate, but also a reflection of just how many people are now infected with COVID. The high number of infections has given the virus more and more opportunities to mutate, and to essentially select the mutations that are the most transmissible, like we saw in the United Kingdom.

Q. Let’s start with a positive. What doesn’t worry you about the mutations we have seen?

A. What does not concern me right now is that the vaccines that are in use in the U.S., the mRNA vaccines produced by Moderna and Pfizer, are producing extremely high levels of antibodies. With these vaccines, the new variants are not escaping vaccination – even the South African variant, which has proven a tougher target for vaccines from other companies.

Q. All right, what does concern you?

A. I am concerned that we don’t know exactly when antibodies from the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines will wane, because the vaccines have only been in circulation a few months. Will the new variants make the period of immunity shorter, and what does that mean for public health? That’s one thing to keep an eye on.

I am also concerned that other vaccines are not doing as well against some variants. A small clinical trial in South Africa showed the AstraZeneca vaccine was less effective at preventing mild to moderate cases of that variant, for example. Another trial showed that the efficacy of Novavax’s vaccine was also reduced in South Africa. It is important to note, though, that these vaccines still seem to be effective at preventing hospitalization and death, which is obviously important. But, to really get us out of this pandemic, we will need to lower transmission of even mild and moderate cases.

A final concern is simply time. The best defense against mutations is reaching herd immunity, so that there is less infection and the virus has less opportunity to mutate. Reaching herd immunity becomes harder when the virus becomes more transmissible, as we have seen with the U.K. variant. As we approach herd immunity, the virus will be under evolutionary pressure to mutate in ways that beat the vaccines. We need to bring infection rates down as much as possible to slow that process.

Q. In that case, the emergence of new variants could extend the timeline of the pandemic, correct?

A. Yes, I think it will inevitably extend the pandemic some, unfortunately, because we will have to get to higher levels of herd immunity. It’s hard to tell if it will extend it by one month, or by another six months. It is encouraging to see infection rates dropping dramatically in the U.K., where they instituted some strict quarantine measures and are really ramping up vaccinations, and in the last two weeks in the U.S., as well.

We have also been given a cushion in the U.S. by the really great news that the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA vaccines are very effective, even against variants. That has given us some wiggle room and ability to withstand this variants, which is truly something to be thankful for.

Q. How can vaccines be adapted to treat other variants that might emerge?

A. The most straightforward solution is to give a booster shot of the vaccine, which both Pfizer and Moderna have begun to study. Additionally, both spike mRNA vaccines, and vaccines based on spike proteins, like the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, are adaptable. It is fairly easy to swap in different variants of the spike protein or mRNA, or even vaccinate for different variants at the same time. [Petri explained more about mRNA vaccines and dosages in this article.]

So, it is not the end of the world if a new variant emerges that escapes current vaccines. I hope that does not happen, but there are solutions available. They would just take more time.

Q. What precautions can people take now to protect themselves against new variants?

A. The same precautions we have been urging – wearing a mask, washing your hands, keeping physical distance, avoiding gatherings, especially indoor gatherings – are still the most effective ways to prevent transmission. Additionally, the CDC has just done a study demonstrating that wearing two masks is more effective in preventing you from getting the virus. I have begun wearing two masks in some public settings.

I would also urge those who are fortunate enough to have been vaccinated to not let it modify their avoidance of risk, and to continue to wear masks and take the other precautions we talk about. We still do not know for sure how vaccines affect our ability to transmit the virus, even if we do not get sick from it, and it is important to continue practicing good public health behaviors until we reach a high level of herd immunity.

Media Contact

Article Information

February 16, 2021

/content/qa-what-new-covid-19-variants-mean-our-vaccine-options