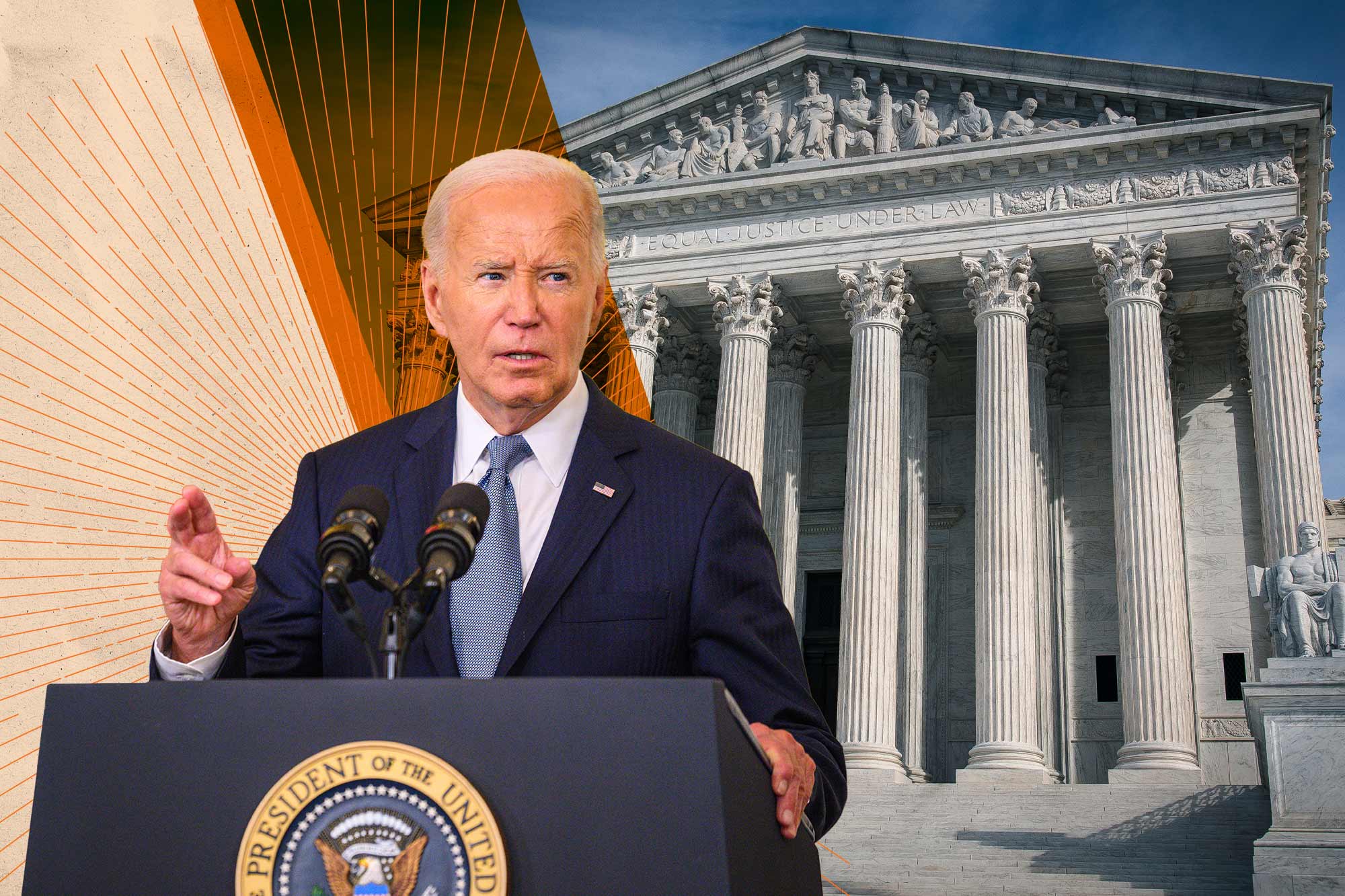

On Monday, President Joe Biden announced he would ask Congress to approve reforms to the U.S. Supreme Court and seek a constitutional amendment to overturn the court’s decision in Trump v. United States granting presidents immunity from criminal prosecution.

To find out more about the proposals, and the chances of them passing, UVA Today checked in with Barbara A. Perry, the Gerald L. Baliles Professor and co-chair of the Presidential Oral History Program at the University of Virginia Miller Center of Public Affairs. Perry is a former judicial fellow at the Supreme Court and was a researcher for former Chief Justice William Rehnquist.

Q. Are the proposals political hyperbole or are there issues with the court that should be addressed?

A. There have been a lot of revelations about gifts and vacations, money going to some justices, as well as controversial decisions, and that’s upset a lot of people in and out of politics.

Of course, if the president, Congress or the court decide the way you want them to, you like them and you approve. If not, then you disapprove. People could review the three reforms being proposed here as, “Oh well, the president and liberals didn’t like the way the court has been deciding cases on abortion, the Voting Rights Act, federal regulatory power and the presidential immunity decision, in particular.” That’s true.

But it’s also true that among Republicans, who agree with these decisions, 57% favor some of these reforms, liked fixed terms, for example.

Q. President Biden is asking Congress to pass binding and enforceable ethics rules and require justices to recuse themselves from cases for conflicts of interest. How’s that different than the code the Supreme Court created for itself in 2023?

A. Unlike codes of ethics for other federal judges, there’s no enforcement in the current Supreme Court code. The justices have been involved in controversy, with Justice Clarence Thomas receiving expensive vacations and gifts from businessmen who have cases coming before the court and not recusing himself. There have also been controversies with political activities by Justice Samuel Alito’s wife and Thomas’ wife.

If there are conflicts of interest, justices should recuse themselves, but in the current code there’s no enforcement and so they don’t have to do it.

(The proposed ethics code is) unlikely to be approved in Congress, of course, but I think at the very least the justices should have done this themselves.

I love the court. I respect the court. I want everybody to respect the court, as the American public has in the past, but this anemic code of conduct that they developed last fall has no enforcement mechanism, and riles the public.

Q. The Supreme Court justices have what amounts to lifetime tenure on the court. How would Biden’s proposed 18-year term impact the court and its membership?

A. Mind you, the Constitution doesn’t say they have life tenure. It says they have tenure for good behavior. The only way to remove a federal judge is that they retire, they resign, they die, (or) they are removed by impeachment and conviction. But no Supreme Court justice has ever been removed by a conviction under impeachment.

We shouldn’t change the court just because we don’t like its decisions. We should focus on the institution, and I think term limits would do that. Most developed democracies in the world have term limits, and Biden is proposing 18 years. That’s way longer than presidents and Congress and would continue to insulate justices from partisan politics and electoral politics.

Barbara A. Perry, Gerald L. Baliles Professor and co-chair of the Presidential Oral History Program at the Miller Center of Public Affairs, says amending the Constitution is not easy. (University Communications photo)

Health has sometimes been an issue for older justices. Alito and Thomas are in their mid-70s now, and they seem fine, but in years past we did have some justices who should have gone off the court due to ill health but didn’t. So this 18-year cap for service seems reasonable, as long as it doesn’t apply to current justices.

The problem with term limits is that it specifically says “for good behavior” in the Constitution. It would likely require a constitutional amendment and we know those are almost impossible to get through, especially in this highly partisan, highly polarized time.

Q. Biden is also calling for a constitutional amendment that would nullify the Supreme Court’s decision expanding immunity for presidents from criminal prosecution. Does it have a chance?

A. The immunity case initially may not seem as partisan or as contentious as abortion or affirmative action because it is systemic and constitutional, rather than overtly political.

Yet the court interpreted the Constitution in a way it had never before been interpreted, to release all presidents, current and former, from any kind of criminal indictment of any action that a judge can be convinced was official. And it obviously aids the Republican presidential candidate.

One of the few ways to overturn the court decision – and the hardest way – is by constitutional amendment. Another way is to wait until the court gets new people on the bench, like when it overturned Plessy v. Ferguson’s separate-but-equal doctrine, or Roe’s abortion decision.

It’s going to be difficult for all three proposals to pass. Anything that is going to require an amendment to the Constitution is probably dead on arrival, but even anything that would require Congress to vote is unlikely the way it’s currently split. But it gives the Democrats another issue to place before the electorate.

Media Contacts

Assistant Editor, UVA Today Office of University Communications

bkm4s@virginia.edu 434-924-3778