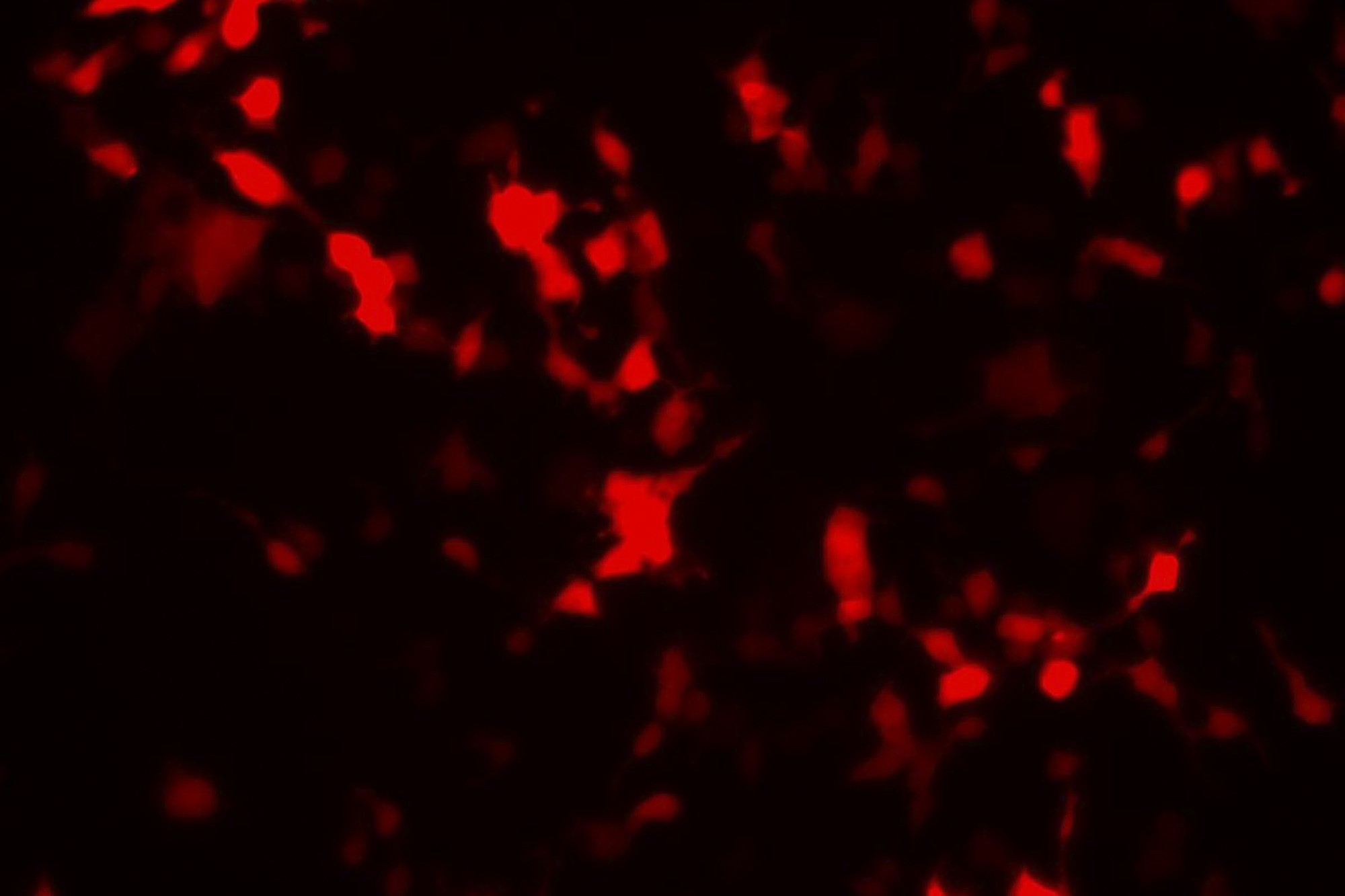

With a little tweak of the color palette, University of Virginia School of Medicine researchers have made it easier for scientists to understand biological processes, track happenings inside individual cells, unravel the mysteries of disease and develop new treatments.

UVA’s Hui-wang Ai and Shen Zhang have developed a simple and effective improvement to fluorescent “biosensors” widely used in scientific and medical research. The biosensors detect specific targets inside cells and sets them aglow, so that scientists can monitor and quantify biological events they otherwise could not.

UVA researchers Hui-wang Ai (left) and Shen Zhang are both part of UVA’s Department of Molecular Physiology and Biological Physics, the Department of Chemistry, the Center for Membrane and Cell Physiology, and the UVA Cancer Center. (Contributed photo)

Most fluorescent protein biosensors give a green or yellow glow, but Ai and Zhang have discovered a way to shift the green to red. This comes with big benefits, including making it easier for scientists to monitor multiple targets at a time and to peer more deeply into tissues.

“This innovative method can convert not only existing biosensors, but also any green biosensors developed in the future,” Ai said. “Multicolor and/or multiplexed imaging with fluorescent biosensors cells will thus become widely accessible.”

Lighting the Way

While there are existing red biosensors, they are typically outperformed by their green counterparts. So scientists have been eager to find ways to shift the green color into red, retaining the benefits of the green sensors while adding new ones, such as reducing the visual confusion that can be caused by the natural fluorescence of tissues and cells.

Ai and Zhang found a solution partly by a stroke of luck – or “serendipity,” as they describe it in a new scientific paper. In the course of their regular lab work, they found that adding a particular amino acid, 3-aminotyrosine, to the green biosensor made it turn red. This is simple to do and quite effective, they report. The red version preserved the brightness, dynamic range and responsiveness of the green sensor, while offering the additional benefits of a red one.

“We modified a panel of green biosensors for metal ions, neurotransmitters and cell metabolites,” Zhang said. “Spontaneous and efficient green-to-red conversion was observed for all tested biosensors, and little optimization on individual sensors was needed.”

The researchers tested their improved biosensor on cells that make insulin in the pancreas. They were able to monitor the effect of high levels of glucose on the cells, gaining new insights and giving the researchers new directions to explore.

They hope their quick-and-easy sensor upgrade will offer similar benefits to many other scientists and lines of scientific research.

“It will have lots of applications,” Ai said, “such as acceleration of our understanding of how pancreas controls insulin secretion or how neuronal activity patterns in the brain correlate with complex behavior.”

Findings Published

The researchers have described their technique in the scientific journal Nature Chemical Biology. Ai and Zhang are both part of UVA’s Department of Molecular Physiology and Biological Physics, UVA’s Department of Chemistry, the Center for Membrane and Cell Physiology, and the UVA Cancer Center.

The research was supported by UVA and the National Institutes of Health, grants R01GM118675, R01GM129291, U01CA230817 and R01DK122253.

To keep up with the latest medical research news from UVA, subscribe to the Making of Medicine blog.

Media Contact

Article Information

October 19, 2020

/content/red-light-means-go-medical-discoveries