Young kids are often excited about science. Their natural curiosity is met by the wonders around them, inspiring them to imagine and then work to discover exactly how things work. A child enamored with jets may eagerly learn all about aerodynamics, thrust, intake and lift, not knowing he is captivated by the physics of flight.

Unfortunately for many, however, that enthusiasm and interest in science begins to wane as they move from the elementary years into middle and high school.

“Our research has shown that the decline in science engagement among young people begins in late elementary school and bottoms out by the end of middle school or the beginning of high school,” said Robert H. Tai, associate professor of education at the University of Virginia School of Education and Human Development. “A lack of science engagement among young people can easily be carried forward into a lack of science engagement as adults. With scientific advances playing ever-growing roles in practically every aspect of our lives, ranging from the personal in terms of the food we eat to the global in terms of slowing climate change, engaging with science in order to make good decisions as adults is critical.”

Efforts to maintain or improve students’ enthusiasm about science, technology, engineering and math, or STEM, subjects through middle school pay off. In his 2006 paper published in the journal Science, Tai showed kids who are interested in science when they are in the eighth grade are two to three times more likely to go into science as adults.

Since that study published, Tai and his team have been working to answer obvious next question: “How do we get and keep students engaged in STEM?”

According to Tai, some studies have found that the way students are taught science, technology, engineering, and math can affect their levels of interest. But understanding how students are taught STEM lessons should not only include the learning experiences happening inside of formal classrooms.

“Whether it is participating in a STEM summer camp, in the National Science Fair competition or the First Robotics Competition, there is evidence that participation in outside-of-school programs can have a positive impact on students’ STEM attitudes,” Tai said. “In this new study, we wanted to identify exactly what these different kinds of programs were doing to get these kids excited about science.”

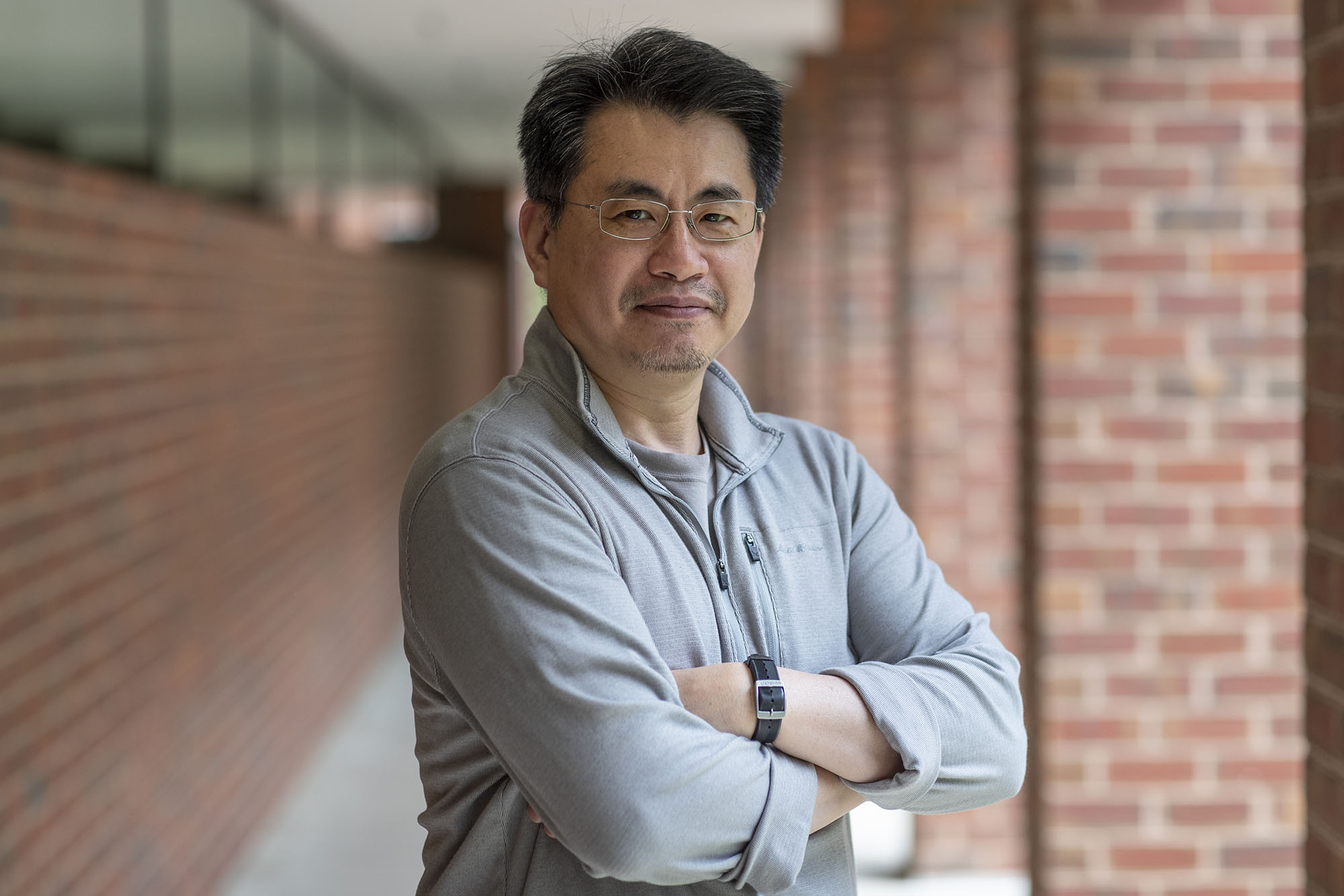

Robert H. Tai is an associate professor of education at UVA’s School of Education and Human Development. (Photo by Sanjay Suchak, University Communications)

In his paper published this month in the Journal of Youth Development, Tai shows that engaging students in STEM is more complex than simply providing hands-on activities.

“Within the field of science education, there is an assumption that kids like to solve problems and figure things out,” Tai said. “That is true. Kids love to complete puzzles and other similar activities. The other side of that assumption is that kids like to create things. But not all kids like to do things with their hands. So, STEM education must be more than that.”

After looking over a number of STEM programs and brainstorming all sorts of activities that could engage kids in science, Tai and his team began to see a pattern of learning activities showing up across programs, even those that seemed to have little in common.

“Programs designed to most effectively engage students were comprised of seven active, intentional learning experiences,” Tai said. “These experiences can happen in both informal and formal settings.”

Named “The Framework,” Tai’s team developed the instrument to measure the presence of these seven experiences: Competing, Collaborating, Creating, Discovering, Performing, Caretaking, and Teaching.

For example, imagine a team of three students, finalists at the National Science Fair, standing before a display of their project about reducing greenhouse gas emissions. They have finalized and displayed their experiment, published and presented their findings, and are now sharing their work with the judges as they pass by. By this time in the fair, the team of students have engaged in all seven learning experiences.

Competing: By nature, the National Science Fair is a competition; students work to place higher than another team. But “competing” can mean more, according to Tai.