The average human swallows 500 to 700 times a day. Imagine if each of those swallows was a struggle.

For many who suffer from esophageal motility disorders like dysphagia that affect the way the muscles in the esophagus deliver food and liquids to the stomach, the act of swallowing can be difficult or even painful. It can turn something as simple as a sip of water into a violent fit of coughing.

Brought on by conditions like gastroesophageal reflux disease, or GERD, degenerative diseases like Parkinson’s disease, and even just old age, these disorders can lead to problems like dehydration, malnutrition, pneumonia and choking, and it affects the quality of life of approximately half a million Americans every year and as many as one in five individuals over the age of 50.

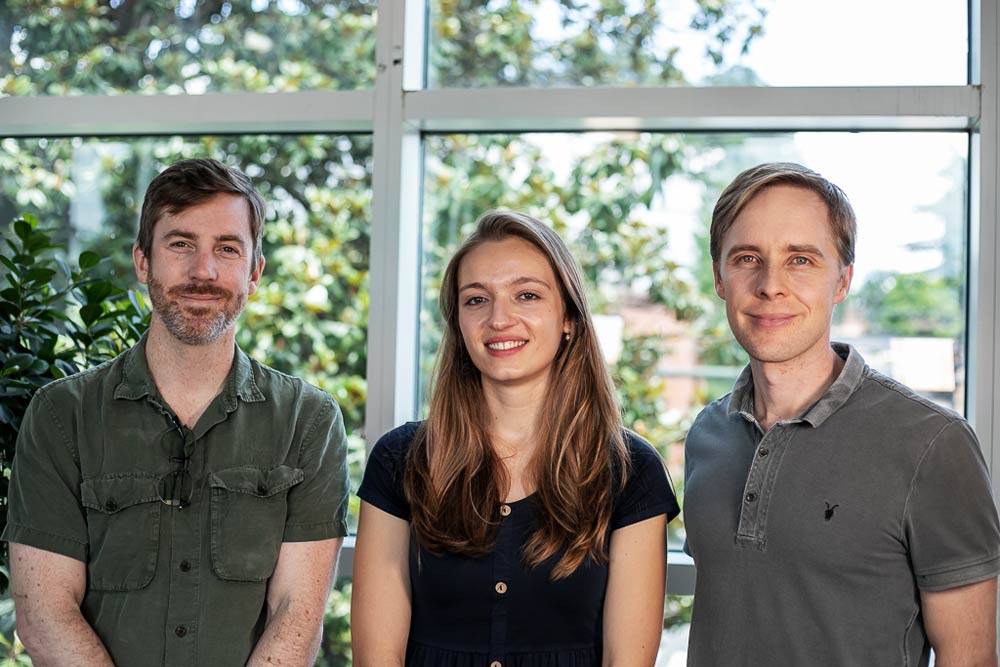

The causes of these conditions are not well understood by medical science, but a study published this month in the journal Cell Reports by a team of scientists from the University of Virginia’s College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences and UVA’s School of Medicine identifies the unique genetic fingerprint of the nerve cells that govern the motor function of the esophagus. According to the scientists involved, this opens a new avenue of approach to the treatment of esophageal motility disorders that could lead to new therapies and new pharmaceuticals, offering hope to those who live with the debilitating effects of dysphagia and other disorders affecting the esophagus.

The study, led by doctoral student Tatiana Coverdell, began as an attempt to identify the neural pathways from the brain that control heart rate. The human body contains a complex array of neural pathways that connect the brain to each of the body’s organs, and much about how these pathways are organized and function is still not understood.