Few moments are more heartbreaking for families of Alzheimer’s disease patients than when a loved one no longer recognizes them. New research from the University of Virginia School of Medicine may reveal why that happens and offer hope for prevention.

UVA’s Harald Sontheimer, graduate student Lata Chaunsali and their colleagues found that when protective structures around brain cells break down, people may lose the ability to recognize loved ones. In lab studies, keeping these structures intact helped mice remember one another.

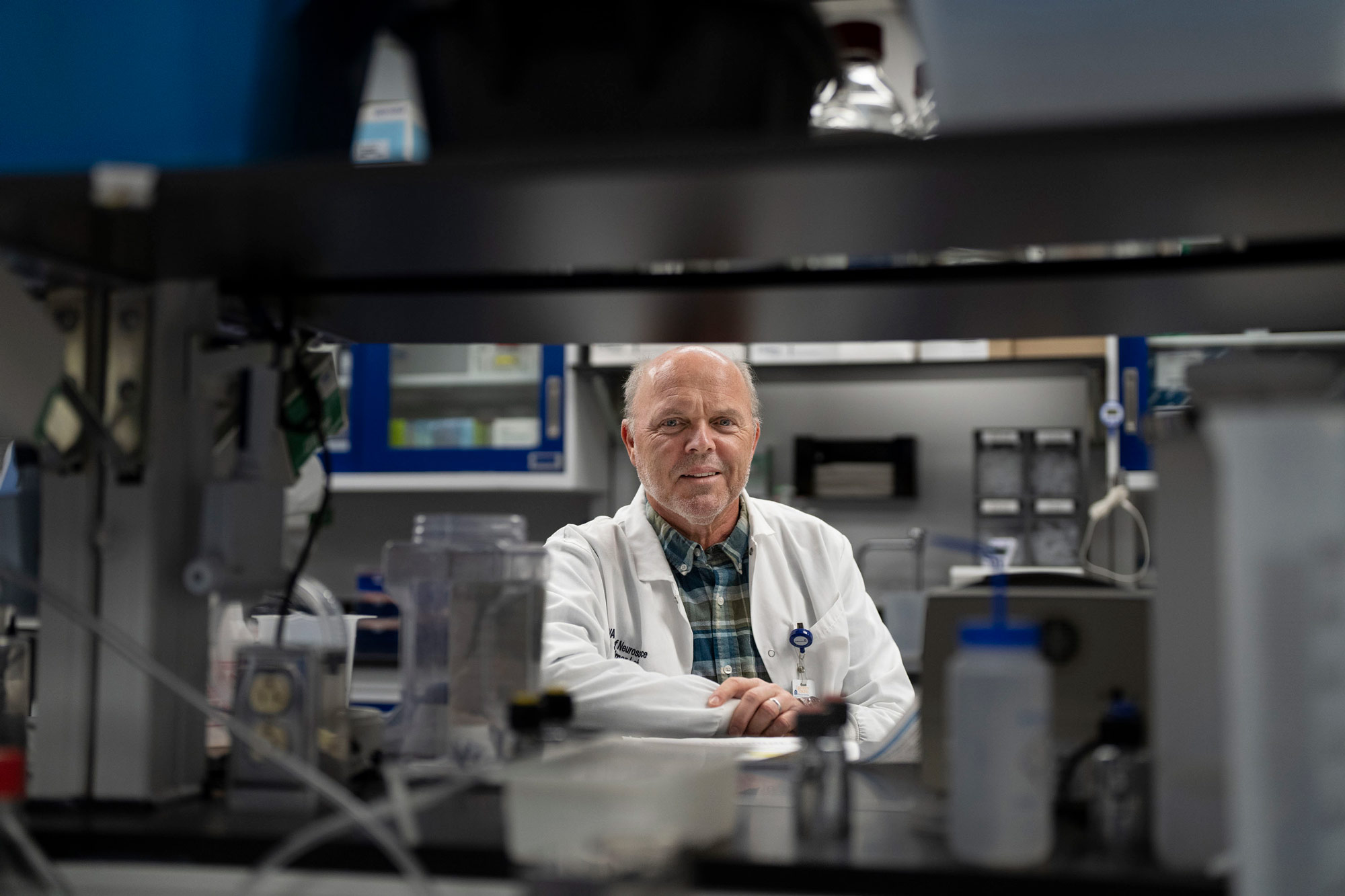

Harald Sontheimer chairs UVA’s Department of Neuroscience and is a member of the UVA Brain Institute. (University Communications photo)

“Finding a structural change that explains a specific memory loss in Alzheimer’s is very exciting,” said Sontheimer, chair of UVA’s Department of Neuroscience and member of the UVA Brain Institute. “It is a completely new target, and we already have suitable drug candidates in hand.”

A growing threat

Alzheimer’s disease affects 55 million people around the world, and that number is expected to grow by 35% in the next five years alone. In response, UVA has established the Harrison Family Translational Research Center in Alzheimer’s and Neurodegenerative Diseases as part of its Paul and Diane Manning Institute of Biotechnology.

The institute aims to accelerate the development of new treatments and cures for some of the world’s most challenging diseases, including Alzheimer’s.

Sontheimer’s research offers insight into how the disease develops. He and his team previously revealed the importance of what are called “perineuronal nets” in the brain. These nets act as protective barriers, ensuring nerve cells communicate properly. This communication is essential for neurons to form and store new memories.

Building on their earlier findings, Sontheimer and his collaborators suspected that disruptions in these protective nets might mark a critical turning point in Alzheimer’s disease. Their latest research supports that theory.