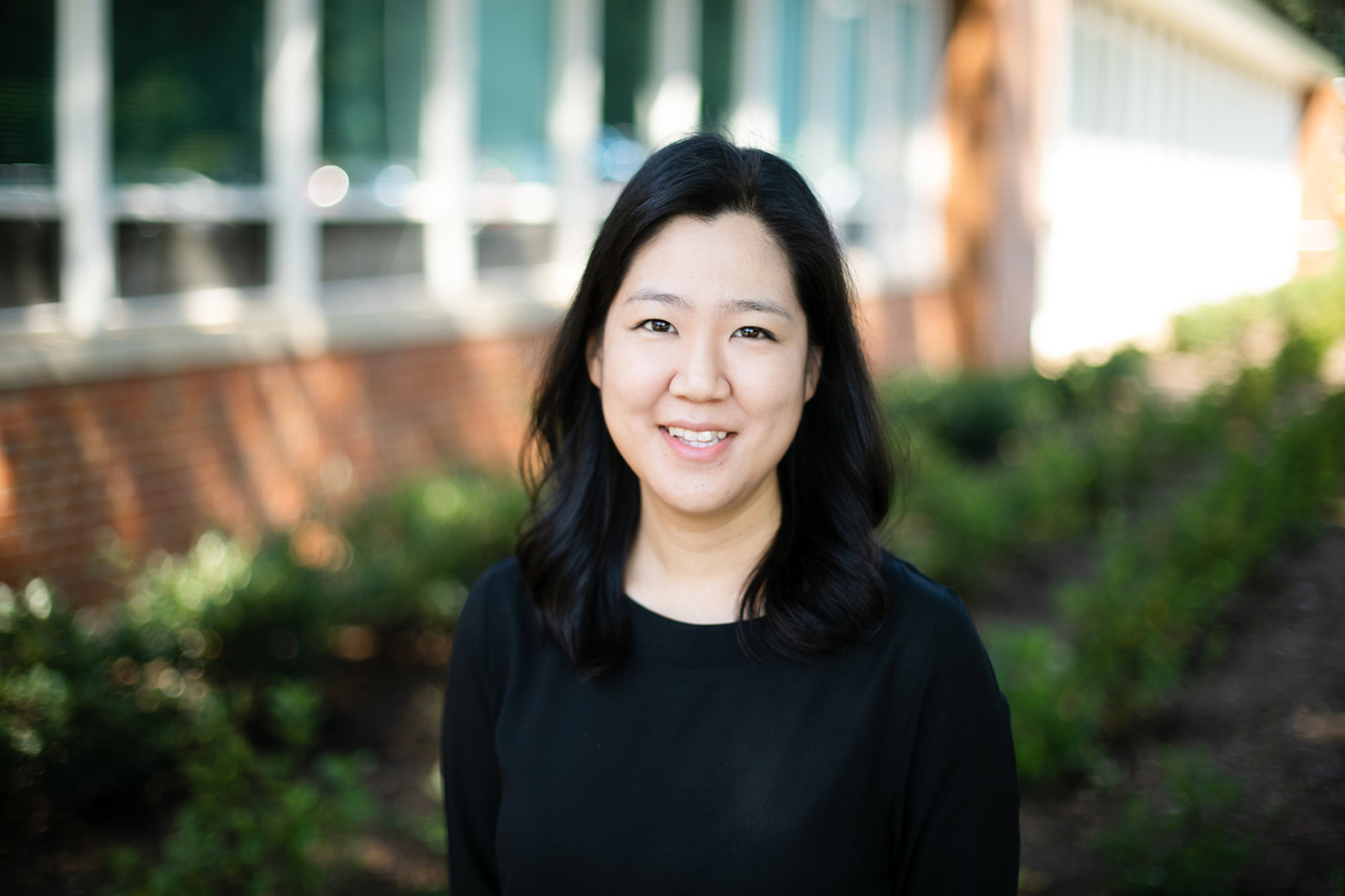

Lieny Jeon’s question was simple, but it brought them to tears.

Once Jeon, the Jane Batten Bicentennial Associate Professor of Early Childhood Education in the University of Virginia’s School of Education and Human Development, decided to research the psychological and physical wellbeing of early childhood educators, she started contacting those who would be participating in her study.

Just asking why they chose their jobs and, more importantly, the hardships involved, sometimes brought the educators to tears.

“More than once, when I explained my study to recruit them, they began to cry,” Jeon said. “One told me that I was the first person to ask about their work and life.”

“No one was looking at teacher wellbeing 10 years ago,” she said. “Thankfully, that has changed. We’re seeing more federal investments in early child care teacher wellbeing, including funds for research.”

During the past several years, federal and state governments increased their monetary investment in early childhood education – and in research into early education. In March, the White House released the 2023 Economic Report of the President, which dedicated an entire chapter to early childhood education and cited several research studies conducted by faculty and alumni of the UVA School of Education and Human Development.

That report includes studies about the psychological wellbeing of child care providers, including the impacts of chronically low pay and pandemic stresses.

And yet, according to Jeon, many early childhood educators continue to feel unseen.